The name Ulrich von Liechtenstein may instantly transport you to the silver screen’s retelling of the Middle Ages, notably the 2001 blockbuster A Knight’s Tale. This vivid cinematic tapestry introduced us to Heath Ledger’s unforgettable portrayal of William Thatcher—a lowly, yet ambitious peasant concealing his identity under the armor of chivalry, seeking both glory in jousting tournaments and the affection of a noblewoman. In a dazzling display lasting over two hours, we were privy to Thatcher’s metamorphosis into a knight, defying his social destiny.

Unfolding within the grandeur of 14th-century Europe, A Knight’s Tale commences at a jousting arena, where the death of Sir Ector, Thatcher’s master, sets an unexpected stage for Thatcher’s prowess. Incited by his unexpected victory, and bolstered by his loyal comrades Roland and Wat, Thatcher embarks on an audacious journey to re-define his social standing, plunging headlong into the tumultuous world of knightly tournaments.

Where is Gelderland and Liechtenstein?

However, Thatcher and his comrades face a significant obstacle: the strict social hierarchy of the medieval period restricts the noble sport of jousting to the privileged classes. Unperturbed, Thatcher ingeniously assumes the moniker “Sir Ulrich von Liechtenstein,” claiming roots in the town of Gelderland.

A casual observer might assume Gelderland and Liechtenstein to be neighboring regions, given the film’s fabricated identity for Ledger’s character. Yet, geography tells a different story. Gelderland, a historical region nestled within the Low Countries, now forms part of contemporary Germany. Liechtenstein, on the other hand, sits comfortably between Austria and Switzerland, a sizable 372 miles (600 km) apart.

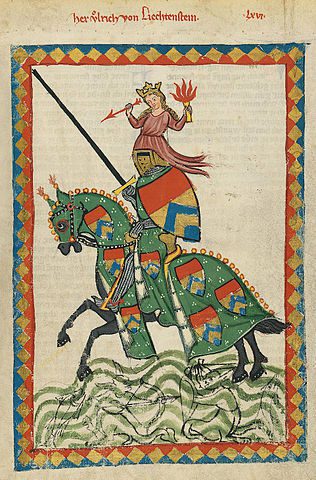

The filmmakers didn’t arbitrarily bestow the moniker “Sir Ulrich von Liechtenstein” upon the humble Thatcher. Rather, this was a deliberate nod to the past, borrowed from a genuine 13th-century knight and poet. Ulrich von Liechtenstein, the historical figure, led a life that was anything but ordinary, punctuated by unreciprocated love, offbeat romantic pursuits, and even, it is claimed, a brief stint in cross-dressing.

So just who was the real Ulrich Von Liechtenstein?

Ulrich von Liechtenstein, born into a moderately affluent noble lineage in the 1200s, traced his roots to what is now known as Austria, but was then the Duchy of Styria. His journey to knighthood began humbly as a page, an experience that offered him a first glimpse of the nobility’s world. His diligence and capabilities caught the attention of Margrave Henry of Istria, a prominent noble from the House of Andechs and son of Duke Berthold IV of Merania. Under his tutelage, von Liechtenstein transitioned into a squire, acquiring skills and lessons that would serve him later in life. His efforts bore fruit in his early 20s when his prowess and dedication earned him the prestigious accolade of a knighthood, conferred upon him by Duke Leopold VI.

The Service of Ladies

While Ulrich von Liechtenstein’s dexterity with a sword was notable enough to earn him a knighthood, his aptitude for the quill was equally impressive. This multifaceted knight morphed into a celebrated poet, illuminating the pages of the 13th-century literary scene with his stirring verses. His seminal work, Frauendienst (The Service of Ladies), penned circa 1250, is a magnificently woven tapestry of his knightly escapades and chivalric deeds—an autobiography steeped in colorful exaggeration and compelling storytelling.

Despite his literary acumen for romantic narratives and the chivalric ideal of honoring a lady, von Liechtenstein’s real-life exploits in the domain of love were less successful. His heart yearned for a particularly elusive noblewoman, who remained indifferent and hard to please despite his unwavering devotion.

Early in his career, von Liechtenstein’s path intertwined with this unnamed noblewoman, a lady senior in age, yet captivating enough to make him smitten. He hoped his unwavering service and dedication would eventually warm her heart. However, the noblewoman rejected his advances with a sharp tongue, often mocking him for his lip deformity.

Undeterred, Ulrich decided to brave a risky, high-cost surgery in Graz, attempting to rectify his physical imperfection. This drastic gesture stirred the noblewoman’s curiosity, prompting her to invite the knight on an outing. Overwhelmed by her status and the sudden turn of events, von Liechtenstein found himself paralyzed, unable to act on his feelings. His hesitation sparked her ire, allegedly leading her to tear out a lock of his hair in frustration.

From that incident onward, the path to the noblewoman’s heart became an uphill battle for von Liechtenstein. For three years, she coldly ignored his existence, including the heartfelt poems and songs he crafted in her honor. His timidity had provoked such anger in her that she forbade him from jousting under her colors—a significant insult in the Middle Ages when bearing a lady’s colors was considered an honor and a token of her favor.

If at first you don’t succeed, try again

Unyielding in the face of his beloved’s continued rebuffs, von Liechtenstein’s resolve only intensified. He wielded his renown as a jouster, hoping to sway her affections by sharing tales of a battle-inflicted finger injury. Yet his first foray into this unique strategy of courtship was met with skepticism. Undeterred, von Liechtenstein took a drastic measure—sending her his severed digit. This unconventional profession of love, though shocking, captivated the noblewoman and seemed to affirm his deep commitment.

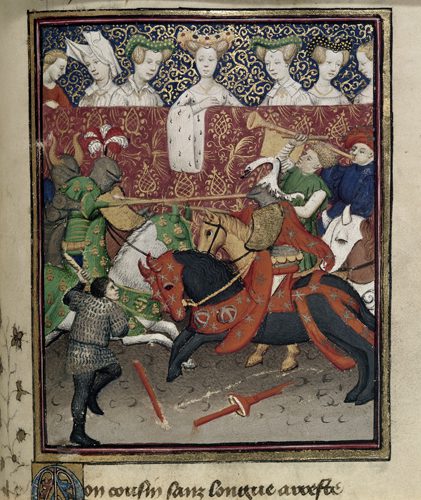

With this extraordinary display of devotion, von Liechtenstein managed to regain her favor and earned the privilege of competing under her banner. Determined to win not only her heart but also the prestige and riches that accompanied jousting victories, he embarked on an extended chivalric expedition across Southern Europe, dubbed “The Journey of Venus.”

For more than five weeks, von Liechtenstein jousted while donning women’s attire, symbolizing the Goddess Venus as a testament to his love and devotion. He would announce his arrival to each city in advance, allowing other knights to prepare for honorable combat in the name of the ladies they served.

This epic quest is vividly detailed in The Service of Ladies, where von Liechtenstein claimed to have shattered an astounding 307 lances. Furthermore, in a generous display of chivalry, he awarded a golden ring to every knight who managed to break a lance against him—a testament to his mastery of the joust and his unwavering devotion to his elusive beloved.

Returning home

The impact of von Liechtenstein’s extraordinary adventures on the noblewoman’s affections remains questionable. Upon his return, she extended an invitation for him to visit her castle, though with the unusual caveat that he must dress as a leper and join the throng of beggars outside her walls. Ever the gallant knight, von Liechtenstein complied, only to be met with her cold indifference. As the story goes, she glanced at him without recognition and nonchalantly strolled past.

Adding insult to injury, she later lowered a rope for von Liechtenstein, suggesting an invitation to climb. However, before he could reach her, she cut the rope short, resulting in an undignified plunge into the water below.

The noblewoman’s aloof, capricious nature and seemingly unreachable status are reminiscent of Lady Jocelyn, the enchanting but seemingly unattainable love interest of William Thatcher in A Knight’s Tale. The uncanny similarities between the historical and fictional accounts serve to highlight the enduring complexity and often fraught nature of courtly love.

From the insights offered in The Service of Ladies and the limited historical records available, it’s evident that Ulrich von Liechtenstein’s thirteenth-century life was extraordinary, even in comparison to the cinematic exploits of William Thatcher. Beyond his jousting prowess and devoted pursuits of courtly romance, von Liechtenstein adeptly managed a thriving estate and navigated the multifaceted responsibilities of knightly duties.

His accomplishments extended beyond the battlefield and romantic endeavors, as evidenced by his later roles as a high-ranking commander and provincial judge. Additionally, he was the proprietor of three significant castles: Strechau, Murau, and Liechtenstein.

While historians suggest that The Service of Ladies may have been consciously amplified for dramatic effect, it nonetheless embodies the period’s ideals of knightly romance. Here, physical prowess and gallantry were seen as essential tools for a knight to stake his claim and win the affections of his chosen lady, encapsulating a vivid illustration of love and chivalry in the Medieval era.