Perhaps the phrase “Er aber, sag’s ihm, er kann mich im Arsche lecken” does not frequently grace your daily conversations, unless, of course, you are of German heritage or have a penchant for stirring up a ruckus. The English equivalent of this curt German retort, resonating with a feisty spirit, can be colloquially understood as “Tell him he can kiss my ass.” More endearingly recognized in the German cultural landscape as the “Swabian salute,” this saucy expression boasts a rich and intriguing history, its roots entwining with the fascinating life of a fiery character from the 16th century.

The tale harks back to the dramatic exploits of a defiant and contentious knight named Götz von Berlichingen, an illustrious figure whose vibrant personality painted the canvas of his time. The legend goes that, in response to an irate bishop demanding his submission, our audacious knight unsheathed this audacious phrase, solidifying it as a memorable artifact in the annals of German folklore. This historical episode injects life and color into the language, underscoring how expressions are not mere linguistic constructs, but often intimate windows into a culture’s history and character.

An embodiment of martial audacity and mercenary fervor, Gottfried “Götz” von Berlichingen (1480–1562) was not your average knight. He stood tall as a feudal soldier, his sword ever-ready to carve a path of carnage through the battlefield — but only for those who could spare a hefty coin. A mercenary of the first order, Götz’s allegiance could be purchased, but never cheaply, a fact well-known to the deep-pocketed Bavarian dukes and sundry influential figures of his era who regularly requisitioned his services.

Yet, this sword-for-hire held a distinct place in the collective memory of the German people, a curious blend of a fearsome mercenary and a champion of the common folk. Parallels can be drawn to the folkloric figure of Robin Hood, as Berlichingen, much like the English outlaw, had a soft spot for the working class. His sympathy for the commoners expressed itself in an unconventional and perilous hobby that occupied his off-duty hours.

Götz, in his rogue pursuit of social justice, was said to kidnap high-born nobles, demanding a hefty ransom for their release. Moreover, he frequently set upon merchant convoys, seizing goods that he would later trade and sell. These activities, while criminal by the standards of nobility, painted him as a rebellious hero among the common people. His life, therefore, presents a fascinating blend of ruthless pragmatism, financial opportunism, and a certain rebellious sympathy for the underprivileged.

“Götz of the Iron Fist”

Gottfried “Götz” von Berlichingen, a knight of infinite resilience and adaptability, was no stranger to the volatile, cut-throat landscape of 16th-century European warfare. Indeed, his military repertoire was vast and diverse, ranging from services rendered to numerous masters in campaigns as wide-reaching as the wars against the Turks in Hungary in 1542, to leading a band of rebels in the German Peasants’ War of 1525. His reputation as a hardened warrior, however, was not his sole claim to historical renown.

In a twist of fate that would forever mark his life, Berlichingen lost his right arm at the tender age of 21 in the crucible of a fierce battle. The circumstances surrounding this event have been a matter of much historical debate. The common consensus is that the mishap occurred during the Battle of Landshut in 1503, a fiery clash sparked by a territorial dispute between the duchies of Bavaria-Munich and Bavaria-Landshut. Legend has it that an enemy cannonball, deflected off the young knight’s sword, triggered a grievous self-inflicted wound that cost him his right arm at the wrist.

For a knight like Götz, whose very livelihood was intertwined with his martial prowess, this personal catastrophe necessitated swift adaptation and resilience. The resolution to his predicament came in the form of an iron prosthetic, a crude but ingeniously crafted replacement for his lost arm. This early example of prosthetics, robust in design and remarkable in its functionality, has since been celebrated as a pioneering feat of 16th-century medical innovation.

The iron hand was not just a testament to its creator’s metallurgical skills but also displayed an astonishing degree of aesthetic detail and mechanical sophistication. Crafted from heavy iron, the prosthetic boasted a half-functional hand, fully articulated at the forearm. It featured two hinges at the top of the palm, enabling the four hook-like fingers to curl inward, thereby facilitating the gripping of a sword. Remarkably, the prosthetic arm bore engraved details mimicking the natural features of a hand – the shapes of fingernails, knuckles, and even the intricate lines of wrinkles, a testament to the creator’s meticulous attention to detail. In the face of adversity, this iron hand helped Berlichingen to continue his military career and remain a formidable force on the battlefield.

An advanced model

While the first iteration of Götz von Berlichingen’s prosthetic hand served him well, the relentless drive for innovation that defines human progress soon led to a markedly more sophisticated version. This second model, though crude by today’s standards, was a marvel of its era, the 16th century, a period of burgeoning technology and nascent scientific understanding. “A clumsy structure, but an ingenious one,” was how the American Journal of Surgery aptly characterized it.

This advanced prosthetic was a significant upgrade from its predecessor, embodying a leap in mechanical and design sophistication. It boasted spring-loaded mechanisms, similar to the ratchet systems found in handcuffs, allowing the fingers to lock into place. This feature dramatically expanded the range of movements possible, providing a more robust grip, and enabling a level of dexterity previously unattainable.

The mechanical enhancements of this second model were particularly advantageous to its wearer’s knightly obligations. Notably, the refined design offered an ease of manipulation that brought mundane tasks within reach. For instance, holding a quill, an essential skill in a world where diplomacy often required written correspondence, became feasible for the knight.

Yet, the most critical improvement lay in the sphere of combat. The new model’s superior grip and range of movement significantly enhanced Berlichingen’s fighting capabilities. It enabled him to securely wield a sword with one hand while managing the reins of a war horse with the other. Such newfound versatility undoubtedly cemented Berlichingen’s reputation as a formidable warrior, despite his disability.

A brief history of prosthetics

The realm of prosthetics has a rich and storied history, stretching back thousands of years, reflecting our innate human yearning for wholeness and functional independence. The first recorded prosthesis, a detailed artificial hallux (or big toe), belonged to an Egyptian noblewoman living between 950 and 710 BC. This seemingly humble appendage recovered from antiquity, reveals much about the role of prosthetics in societal integration, identity formation, and preserving one’s ability to partake in cultural norms. In this case, the artificial toe would have enabled its wearer to comfortably don the traditional sandals of the period, epitomizing the dual role of prosthetics in both practicality and societal conformity.

Venturing into the annals of Ancient Rome, we encounter General Marcus Sergius, the first recorded individual to wield an artificial limb. His narrative mirrors that of our 16th-century knight, Götz von Berlichingen. Sergius, having lost his right hand in the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), was furnished with an iron prosthesis, allowing him to continue his military career. The parallels between these two warriors underline the enduring practicality and significance of prosthetics across millennia.

While the prosthetic technologies of these eras were relatively rudimentary, the tide turned dramatically between 1500 and 1800 AD. This period, marred by warfare and its resultant casualties, served as a crucible for innovation in both amputation surgery and prosthetic development. The 16th century was a particularly pivotal era, witnessing breakthroughs that would shape the future of prosthetics.

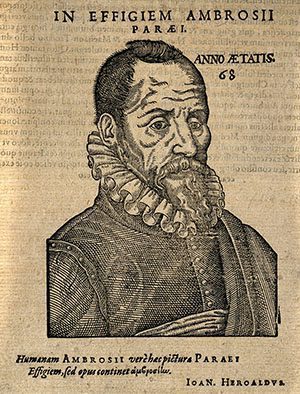

Among the luminaries of this era, few shine brighter than Ambroise Paré (1510–1590), the official royal surgeon for multiple French kings. Paré, hailed as one of the founding fathers of surgery and modern forensic pathology, made significant strides in surgical amputation techniques and prosthetic design. His pioneering innovations included a hinged prosthetic hand and a leg featuring a locking knee joint, concepts that remain integral to the modern prosthetic design. Paré’s work set the stage for subsequent advancements, creating a lasting legacy that resonates in the field of prosthetics today. Through these historical vignettes, we are reminded that the art of prosthetics has long been an integral part of our human journey, a testament to our unwavering resilience and tenacity in the face of adversity.

Götz von Berlichingen’s story inspired Goethe

The remarkable saga of Götz von Berlichingen, the spirited 16th-century knight known as “Götz of the Iron Hand,” didn’t cease upon his retirement from the battlefield at the ripe age of 64. His innovative iron prosthetic, while not a flawless replacement for his original limb, proved to be an instrumental ally throughout his adventurous life, granting him not just an extended career, but also a unique identity.

In his golden years, Berlichingen chose to set aside his sword and take up the quill, creating an autobiography that offered an intimate lens into his dynamic world. While the manuscript was left unpublished at his death in 1562, it resurfaced in 1731.

It was then that the manuscript caught the eye of the distinguished German writer and statesman, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who was so profoundly stirred by Berlichingen’s tale that he immortalized it in a dramatic play aptly titled “Götz von Berlichingen” (1773). The play vividly depicts Berlichingen as a German Robin Hood-like figure, a complex hero wielding his might to protect the vulnerable. His legendary iron hand serves as a powerful symbol of his courage and resilience, epitomized at the moment when he, declining to offer his iron hand for a handshake, eloquently informs a friar, “My right, although useful in war, is insensitive to the touch of love; it is disguised by a glove; you see, it is made of iron.”

This poignant imagery—Berlichingen placing his iron hand over his heart—is commemorated in a plaque in the southwestern German municipality of Weisenheim, serving as a visual tribute to the chivalrous knight and his extraordinary journey. The knight’s legacy is further preserved in his native town of Jagsthausen, where, in defiance of the passage of time that often erases tangible historical artifacts, Berlichingen’s iron hand endures. On display at the local castle museum, the prosthetic continues to captivate and inspire, a vivid symbol of resilience, innovation, and the relentless pursuit of life – encapsulating the essence of the unforgettable Götz von Berlichingen.