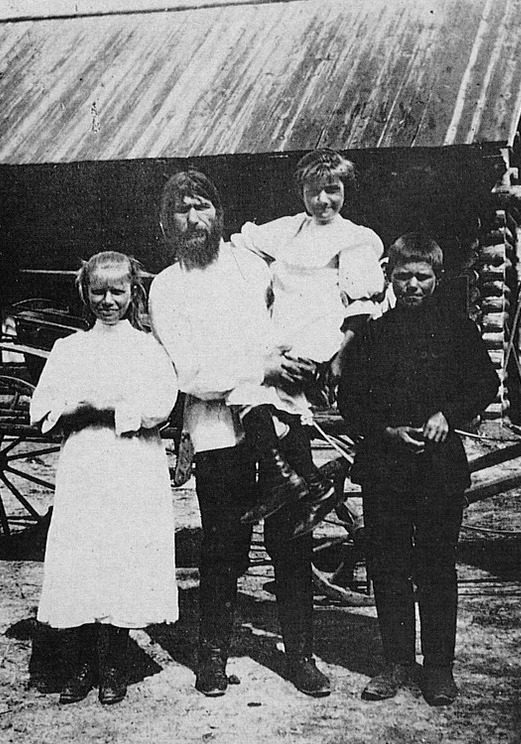

Born to a humble peasant family in the rural expanses of Pokrovskoe, Siberia, in 1899, Maria Rasputin’s life was anything but ordinary. Daughter of the notorious “mad monk” Grigori Rasputin, she walked a path riddled with profound contrasts and dramatic turns. From the rustic simplicity of her birthplace to the gilded halls of Russia’s elite, only to later descend into a life marked by fugitive survival after her father’s vicious assassination, Maria’s story bristles with the harsh contrasts of her epoch. Yet, to truly understand her tale, we must journey back to its inception.

As Maria etched in her adolescent diary, “I was born in 1899 in the village of Pokrovskoe in the county of Tobolsk. My parents are peasants, simple folk. Our family—father, mother, grandfather (my father’s father), my brother, sister, and myself—share a peaceful existence. Despite occasional spats with my siblings, especially my sister, there’s harmony. Yet, our lives are touched by the extraordinary. My father is a significant figure, beloved by the Sovereign, which lends our lives an uncanny tint of the extraordinary.”

This rustic life of hers, so charmingly depicted in her diary, stood in stark contrast to the tumultuous saga that unfolded. It’s a saga intertwined with Russia’s historical narrative, seen through the eyes of an ordinary girl born into extraordinary circumstances. A tale that deserves to be heard, as we trace Maria Rasputin’s life from the simple Siberian village to the whirlwind of controversies that marked her years as the ‘Mad Monk’s’ daughter.

“Mad Monk” Grigori Rasputin

The figure of Grigori Rasputin, Maria’s father, was a paradox in itself—a starets or a spiritual elder, whose ways of life often contradicted the common perceptions of piety. His journey began traversing the vast expanse of Russia, delivering sermons, and offering comfort to those grappling with life’s harsh realities. Despite the fervor surrounding her father’s perceived mystical abilities, Maria remained skeptical, yet never dared to challenge him publicly. She recollects his stern demeanor, and his relentless insistence on rigorous prayer routines and fasting sessions, prompted by a range of events from anniversaries to acts of penance.

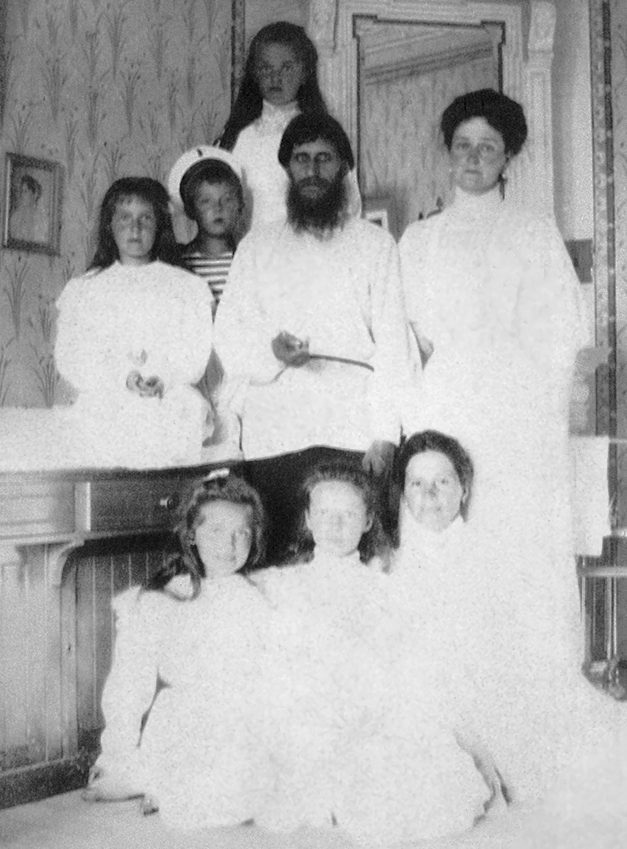

In 1906, their humble life underwent a seismic shift when Grigori Rasputin was summoned to the royal court in St. Petersburg. His reputed miracle of saving the life of Alexei, the hemophilic son of Empress Alexandra, secured him an esteemed place within the Romanov household. This turn of events led to Maria and her sister being uprooted from their modest dwelling and being ensconced in the sophisticated environs of the royal court to be molded into “refined young ladies.”

Their mother, however, elected to remain in Pokrovskoe, opting to maintain their rustic homestead with her son. Empress Alexandra, aware of the void left by Rasputin’s preoccupation with his royal obligations and the absence of the girl’s mother, appointed a governess to attend to their care and education. Maria remembered the time with gratitude, “She found a governess to look after us and take us out and helped us to make up for the lost time by making good the considerable gaps in our early education.”

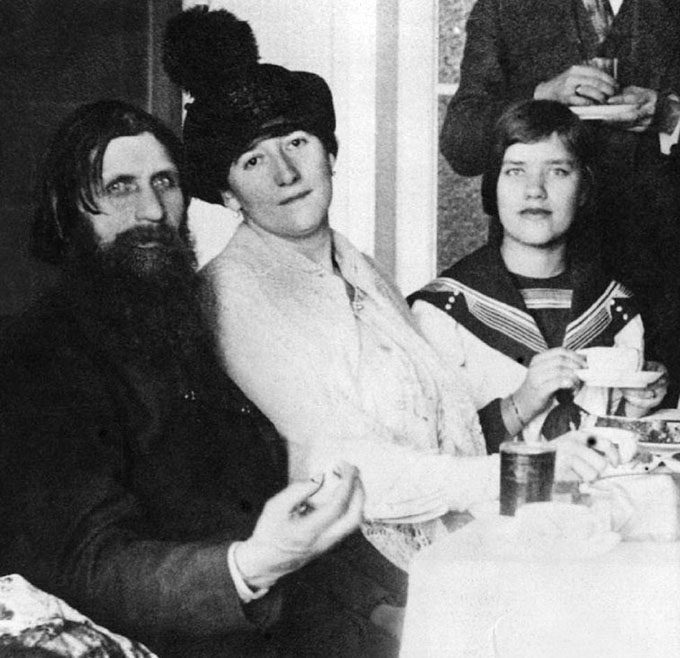

Over time, Maria found herself shouldering the responsibilities of an unofficial hostess, dutifully assisting her father during his royal receptions. It was a role she had never sought, yet one that she carried out with grace and tact, reflecting a maturity beyond her years.

Despite the mounting power and influence of Grigori Rasputin, marred by controversy and widespread public disapproval, Maria’s memories of her father remained relatively untainted. In her perception, he was merely a simple man, his penetrating blue eyes reflecting a peasant’s unyielding faith in prayer. She reminisced about a stern patriarch, committed to ensuring his daughters were cultivated and devout.

“Venturing out alone was a rarity for us, and infrequent were our visits to matinee shows. As adolescence dawned, and young men began to hover around us, my father assumed the role of the most stringent of chaperones. No suitor could enjoy a tête-à-tête extending beyond half an hour; any such attempt would witness my father’s abrupt intrusion, followed by the unfortunate lad being promptly shown the door. The only engagement not curtailed to half an hour was the seemingly endless time devoted to prayers! We prayed together, every dawn and dusk. Sundays saw us spend the morning in the church, while most of the afternoon was devoted to worship. The hours spent kneeling on the cold, stone floor felt interminably long to my sister and me. However, the long skirts of the era provided us with a convenient ruse; we could clandestinely perch on our heels during prayer, evading my father’s watchful gaze!”

The narrative spun by Maria about her father, Grigori Rasputin, stands in stark contrast to the public perception of a debauched, manipulative mystic, wielding undue influence over the desperate Empress Alexandra, oblivious to the sinister motives lurking in her earnest quest to cure her son Alexei. Rasputin was widely regarded as a drunkard and a seducer, exploiting his privileged position at the royal court to sway the royal couple, even as the geopolitical climate around the Romanovs teetered on the brink of chaos. His actions were purportedly instrumental in discrediting the Tsarist regime, fuelling the Russian Revolution, and precipitating the fall of the Romanov dynasty.

Maria, in her twilight years, conceded her limited knowledge about her father’s activities during her youth. Some accounts pointed to his rampant sexual exploits, allegations of sexual assaults on young women, and subversive anti-monarchical inclinations. Rumors circulated about his illegitimate children, though none were definitively proven. Despite such controversial whispers surrounding her father’s life, Maria’s recollections of him remain a testament to a different Rasputin – a stern, religious family man rather than the notorious ‘mad monk.’

Maria Rasputin’s life takes a turn for the worst

During her tenure within the regal milieu, Maria formed close friendships with the four daughters of Nicholas and Alexandra, the Romanov princesses. Yet, her idyllic immersion in royal life was destined for a rather abrupt and tragic end.

As the world plunged into the throes of World War I, the once-celebrated Grigori Rasputin spiraled increasingly out of control. His reputation as the “mad monk” attracted a growing swarm of malevolent scrutiny. Amidst a country descending into chaos, Rasputin found himself in the crosshairs of disgruntled aristocrats and burgeoning revolutionary forces, each viewing him as a blight on the Russian monarchy. Several unsuccessful attempts were made on his life during this tumultuous period until the fateful night when Prince Felix Yusupov and his accomplices took matters into their own hands. It is widely accepted that Rasputin was poisoned, shot, and subsequently cast into the icy depths of the Neva River. His lifeless body, frozen by the merciless winter, was discovered several days later. Heartbreakingly, it was his own daughter, Maria, who had to perform the grievous duty of identifying the corpse. One can barely comprehend the profound emotional turmoil such a grisly task must have inflicted upon a young woman barely out of her teens.

Tragically, the horror did not end with the recognition of her father’s lifeless body. The murder of Rasputin, far from bringing respite, only prefaced further chaos for Maria and her sister. As the nation erupted into the frenzy of the Russian Civil War, their lives were thrust into imminent danger. The sisters were compelled to make a desperate flight for safety. Their quiet lives within the royal circle were ripped away in an instant. Maria vividly recounted the moment the Empress implored her and her sister to flee: “Go, my children, leave us, leave us quickly; we are being imprisoned.” This poignant decree signaled the end of their royal fantasy and the commencement of life on the run.

Fugitive life and fleeing to continental Europe

Following the harrowing escape, Maria and her sister Varvara sought refuge in the comparative safety of their mother’s home in Pokrovskoe. Maria then entered into a hasty marriage with Boris Soloviev, thrusting them into a life of evading capture and a constant state of flight. After enduring a perilous existence on the run, they finally managed to cross the borders and escape to the relative safety of continental Europe. In this new, uncertain life, Maria was blessed with two daughters: Tatiana and Maria. The young family found a semblance of stability in Paris, even as they lived in the shadow of their infamous ancestry.

However, this stability was fleeting. Boris passed away in 1926, his health faltering under the strain of relentless hardship. Maria was left a widow, a single mother trying to navigate her way through a life fraught with challenges. As she poignantly wrote, Boris was “worn out with privations and the work beyond his strength that he accepted to preserve us from dying of hunger.”

Meanwhile, in the Eastern reaches of Europe, the once regal Romanovs were brutally murdered in 1918. Back in the homeland, they had left behind, Maria’s mother and brother vanished into the labyrinthine Soviet gulags of Siberia. Despite these tragic circumstances, Maria found the fortitude to carve out a new life in the West. It was a modest existence, stripped of the royal privileges she had once enjoyed, but Maria saw it for what it truly was—a lifeline. Demonstrating an indomitable will, she provided for her daughters by taking on work as a lady’s maid and companion to a wealthy Russian exile.

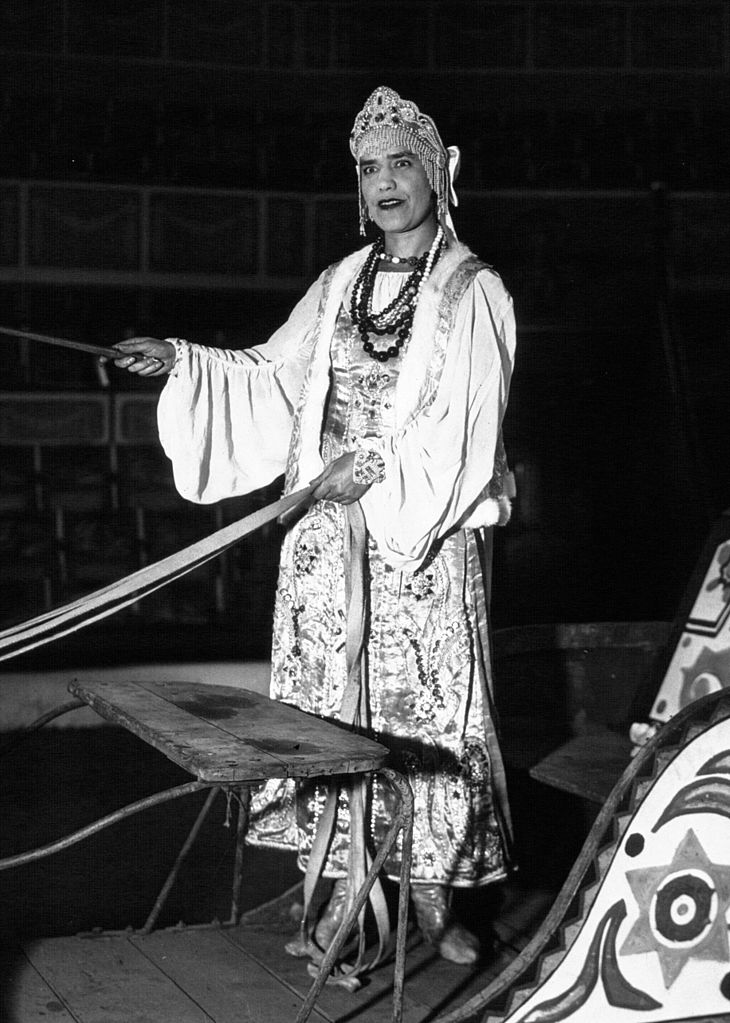

An unexpected turn of events propelled Maria into the spotlight when she was approached with an offer to become a cabaret dancer in Bucharest. In a self-deprecating admission, Maria later conceded, “This was because of my name, not because of my dancing.” For several years, Maria trod the boards across Europe, performing under the limelight as audiences were drawn to the novelty of watching “the daughter of the mad monk” in action. This unusual stint in her life seemed to underline the resilience and adaptability that marked Maria’s extraordinary journey from the royal court to the cabaret stage.

Maria Rasputin publishes her first book

Unfazed by the sudden limelight that her dancing career brought her, Maria made a surprising foray into the literary world. In 1929, she penned her first book, aptly titled The Real Rasputin. The book sought to exonerate her father, offering an alternative perspective to the infamous “mad monk” caricature that had become synonymous with Grigori Rasputin’s name. Not content with a single account, Maria followed this up with another publication in 1932, steadfast in her pursuit to restore her father’s tarnished reputation.

Maria’s desire to undertake such a literary endeavor was not born out of a newfound passion for writing but rather a deeper, more personal motivation. As she candidly stated, “If I thought myself capable of undertaking a literary career, I should not today be struggling to earn my daily bread as a trainer of wild animals… it is my desire to consecrate myself to a task, direct the whole of my life towards one goal, that of giving back to my father his true character.”

Maria’s journey took another unexpected turn as she transitioned from the glitz of cabaret dancing to a role vastly different—she became an animal trainer in a traveling circus. This unconventional career choice might have seemed audacious, even reckless, to some. But for Maria, it was just another challenge to surmount. When questioned about the perceived danger of stepping into a cage with wild animals, her response was as defiant as it was poignant: “Why not? I have been in a cage with Bolsheviks.”

This wry observation encapsulates Maria Rasputin’s remarkable resilience and unwavering spirit. Throughout her life, she navigated a labyrinth of personal and political upheavals, drawing upon an inner strength cultivated during her formative years amidst the turbulence of the Russian court. Whether in the embrace of the royal court, in the shadow of the guillotine, in the public eye of the cabaret stage, or in the iron-clad confines of an animal cage, Maria exhibited incredible adaptability and tenacity, forever marked by her lineage as the daughter of the infamous Grigori Rasputin.

Immigrating to America

In the throes of the 1930s, Maria journeyed across the Atlantic, seeking solace in the New World. She joined the ranks of the Ringling Brothers Circus in America, where she continued to test her mettle as an animal trainer. This transition, however, was not without its hardships. She had to endure the heartbreak of leaving her beloved daughters behind in Europe. Adding to her woes, her time in the circus was abruptly cut short when a bear she was handling turned on her, leaving her severely mauled and unable to continue her high-risk career.

Attempting to find some semblance of normalcy amidst her turbulent life, Maria sought companionship in her second husband, Gregory Bern, an electrical engineer. But alas, this union was far from the haven of peace that she might have hoped for. Maria found herself in a relationship characterized by abuse and torment, which culminated in Bern abandoning her after several grueling years.

Post-divorce, Maria carved out a new life for herself in the residential neighborhood of Silverlake, Los Angeles. Reimagining her career yet again, she put her tenacity and grit to work in an entirely different arena—the shipyards of San Pedro. She secured employment as a machinist, a role far removed from the grandeur of royal circles and the adrenaline of the circus but one that offered her the dignity of self-reliance.

Following her retirement, Maria sustained herself by providing services as a babysitter and caregiver. In her twilight years, she found herself retracing her past for the public eye, offering interviews when financial necessity beckoned. Curiously enough, her account of events appeared to fluctuate, depending largely on her audience. The discrepancies in her narratives lent an additional layer of mystery to Maria Rasputin’s already captivating story, keeping her inextricably bound to the enigmatic legacy of her infamous father, Grigori Rasputin.

Was Maria Rasputin who she claimed she was?

Such an enigmatic saga has, quite expectedly, given rise to an assortment of doubts and speculations. A prevalent belief that arose over time was that Maria Rasputin might not be who she claimed to be, a suspicion fueled by her gravitation toward careers in the public eye, often related to entertainment. These professions, although seemingly innocent, cast a shadow of doubt on the authenticity of her identity.

This skepticism was not unfounded. The riotous era following the assassination of the Romanov family saw a surge of individuals stepping forward, claiming ties to the famed lineage. Many professed to be a surviving Romanov, while others declared themselves heirs of Rasputin. The phenomenon was so widespread that Vladimir Smirnov, the co-founder of Russia’s first private museum dedicated to Rasputin, made light of the situation: “More than a hundred Marias, Anastasias, and Aleksei’s survived the execution in the cellar of the Ipatiev House. Now it’s the turn of Rasputin’s descendants.”

Despite the cloud of uncertainty surrounding her identity, many accounts corroborate the extraordinary journey of Maria Rasputin, affirming that she indeed managed to escape the nightmarish clutches of war and carve out a life of her own, far from her homeland’s violent reality. The life she led can be described in many ways, but perhaps most fittingly, it was extraordinary in every sense of the word. From her birth in a humble peasant family to her unique stint in royal circles, from her thrilling escapades in European cabarets to her gritty survival in the shipyards of America, the saga of Maria Rasputin unfurls as a compelling narrative of perseverance, undying tenacity, and spirit, artfully entwined with the historical tapestry of her era.