The Erfurt latrine disaster remains the most famous scatological tragedy in history. In July 1184, a terrible accident saw at least 60 German nobles die in human excrement, after they fell into the latrine cesspit below the monastery of St Peter’s Church in Erfurt. The future Holy Roman Emperor, Heinrich VI, only survived by hanging on to a window frame. Despite his lucky escape, this toilet tragedy would remain with him until his dying day.

Read on as we look at the circumstances behind this bizarre event, the fates of the noblemen involved, and what it meant for the future of the Holy Roman Empire.

Background to the disaster

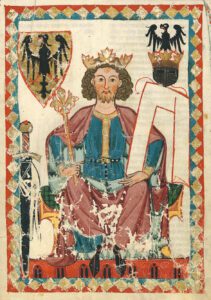

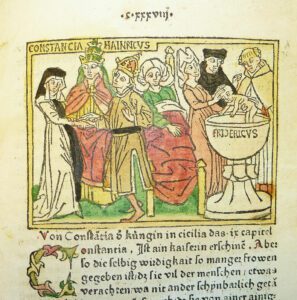

King Heinrich VI (anglicized as Henry VI) was the son of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa. At the time of the latrine disaster, he was only 19 years old, but he was already the king of Germany. In due time, he would succeed his father as ruler of the Holy Roman Empire. This decentralized realm spanned modern-day Germany and parts of Italy and France and was recognized by the Catholic Church as the rightful continuation of ancient Rome.

While preparing for an invasion of Poland, the young monarch set up a seat in Erfurt, located in the Dutchy of Thuringia. Soon afterward, he discovered that all was not well.

Power struggles

The German empire was still recovering from the Investiture Controversy, which had seen religious and secular leaders battle over who had the right to appoint archbishops—an important position, both politically and within the Church. While the conflict was officially resolved, tension remained between feudal nobles and religious leaders.

This resulted in a land dispute in the Duchy of Thuringia. Conrad of Wittelsbach, the Archbishop of Mainz, began the construction of a castle on a hill in Heiligenburg in 1180. This castle lay very close to the border of Thuringia and was built specifically for protection from the landgrave (duke) of that duchy, Ludwig III, who was King Heinrich’s cousin. Of course, Ludwig took this as a provocation, and the two fell into a heated land dispute, with various other noblemen choosing sides.

The diet at St. Peter’s Church

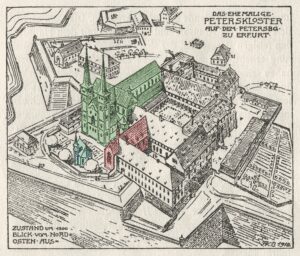

Wanting to end this conflict and hoping to discourage similar conflicts among other leading nobles, the young German king called a formal diet—or assembly meeting—to resolve the situation. Hundreds of nobles assembled in the rectory in the St Peter’s Church monastery, located in the Petersberg Citadel in Erfurt.

The monastery latrine

It is important to note that latrines were quite basic in medieval Europe, just holes in the ground to capture waste. Even in larger, more sophisticated buildings, like the monastery at St. Peter’s, the toilets were still just sloping holes, which delivered waste to large cesspits buried in the ground. These were deep and murky, filled with quicksand-like filth that harbored deadly bacteria and parasites.

But this was normal for the Middle Ages. As Heinrich arranged his meeting on the upper floor of St Peter’s Church, no one thought about the cesspit far below.

The Erfurt latrine disaster

On July 26, 1184, nobles from around the empire had crowded together in the largest room of St Peter’s Church, discussing land control in the region at Heinrich’s request. It turned out, however, that hundreds of nobles were more than the old wooden floor could handle; immediately after the start of the meeting, the floor collapsed, plunging the group into the depths of the monastery.

Another level lay directly beneath them. This, too, gave way, and the nobles continued falling, now accompanied by a mass of wooden beams and other debris. The next floor was the latrine, where the monks dressed and relieved themselves. It was not sturdy enough to survive so much weight collapsing onto it. The plummet continued without pause, until the unfortunate nobles found themselves at the very bottom of the building’s structure, immersed in a dark, putrid realm of concentrated excrement: the cesspit.

A foul and filthy fate

At least 60 men perished that day. It may have been as many as 100. Some died from the fall or from being battered by their flailing companions, while others suffocated in the cesspit. Some who survived the drop became sick after contact with human excrement and died later.

According to the Chronicle of Saint Peter of Erfurt, the king survived by hanging onto the iron rails of a stained-glass window frame. He and Archbishop Conrad happened to be at the edge of the room at the time of the collapse, which ended up saving both of their lives. The pair had to hang there, dangling over the cesspool full of dying men, until people from the Petersberg Citadel arrived with ladders to save them. After his rescue, the king left the city immediately.

A matter of luck

The archbishop’s rival, Duke Ludwig III of Thuringia, also survived, though he fell into the cesspit with his fellow nobles and had to climb out. He would have needed some time to recover from the battering and the infections that no doubt ensued. Later on, in 1190, he died on a ship returning from a crusade in the Holy Land, and his entrails were buried on the island of Cyprus, while his bones were taken to the monastery at Reinhardsbrunn.

While the three protagonists survived, many high-ranking officials of the middle ages were not so fortunate. Among the dead were Heinrich von Schwarzburg, Hesse Gozmar von Ziegenhayn, Burkard von Wartberg, and Fredrich von Kirchberg—to name just a few counts, barons, and other eminences from Germany’s most prominent households.

Historical aftermath

While our records from the period are spotty, the Erfurt latrine disaster would have significantly impacted local politics. The sudden deaths of so many noblemen would have significantly changed the region’s landscape, particularly given the fractious nature of the Holy Roman Empire.

The young King Heinrich VI (King Henry), who had barely escaped the cesspool, became a prominent historical figure. He succeeded his father as Holy Roman Emperor in 1191 and conquered Sicily in 1194. As was common for monarchs of that time, he added King of Sicily to a growing list of titles, with the acquisition making him the most powerful ruler in the Mediterranean. He even threatened to invade the Byzantine Empire, only desisting in exchange for a very handsome ransom.

The death of Heinrich VI

After this string of successes, Heinrich had the confidence—or was it hubris?—to plan a crusade to the Holy Land. In September 1197, however, he fell seriously ill with chills and fever; it may have been malaria, but poisoning could not be ruled out. His death on September 28 plunged the German Empire into a 17-year dispute for the throne.

Heinrich was only 32 when he passed, cutting short what might otherwise have been a long and illustrious reign. Looking at his mysterious sickness and the untimely death that ensued, one must ask the question—had that fateful day in Erfurt come back to haunt him?