The most misunderstood monarch in the Spanish Habsburg dynasty, King Charles II may also be one of the most misunderstood monarchs in all of modern history. By all accounts, he was not a monster, but a shy and self-effacing person; he was also an able diplomat, genial and generous; finally, he was a decent rival of Louis XIV for European hegemony, at a time when France was rapidly emerging as the leading power on the continent.

Yet, he’s best remembered today for his prominent jaw, his numerous ailments and illnesses, and for being alive much longer than he was expected to—despite dying at the young age of 39! His death, when it finally happened, plunged the Old Continent into a series of bloody conflicts jointly known as the War of the Spanish Succession—which marked the first quarter of the 18th century, and changed the course of European history forever.

The establishment of the Spanish Habsburg Dynasty

Тhere would have never been a Charles II of Spain if there hadn’t been a Charles V before him; the two mark the beginning and the end of Habsburg Spain, a time of great prosperity and growth for the country, as well as a period formative of the idea of “Spain” in the sense that we know it today. So, let’s rewind and give a little context to our story.

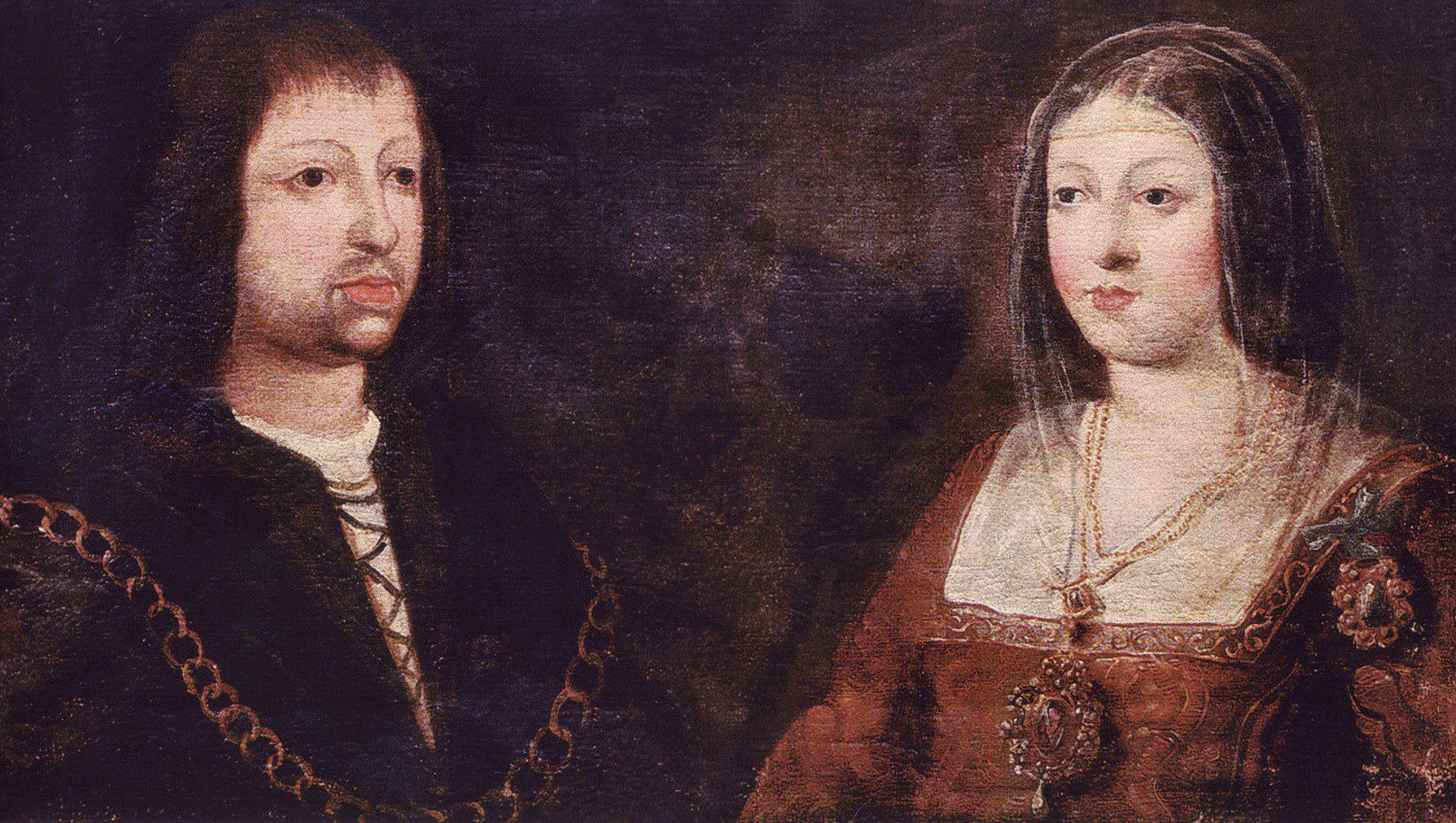

The foundation of Spain can be traced back to October 19, 1469, when the marriage between Isabella I of Castille and Ferdinand II of Aragon—later proclaimed the Catholic Monarchs by Pope Alexander VI—led to the fusion of the two largest kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula. This eventually resulted in the de facto unification of the country, which was famously crowned with the conquest of Granada in 1492, the last Muslim territory in Western Europe.

Now, even though the Catholic Monarchs had seven children, they only had one son—John, Prince of Asturias—but he passed away at the early age of 18, in 1497. Therefore, when Isabella died in 1504, the crown of Castilla passed to Joanna, the couple’s oldest living daughter, and her husband Philip the Handsome, Archduke of Austria of the House of Habsburg. Philip died before his father—Maximilian I, the Holy Roman Emperor—so he inherited neither his father’s territories nor his title. His oldest son, Charles, did both in 1516, thereby adding the expanding Spanish Empire to the Habsburg territories in Europe. A new empire was born, one of the largest in history.

Between two Charles’s: Habsburg Spain from King Charles V to King Charles II

Charles I, the first Habsburg king of Spain, is better known today as Charles V, since he was the fifth Holy Roman Emperor with that name. A capable ruler, he revived the medieval concept of Res publica Christiana, and spent his entire life attempting to defend the totality of the Holy Roman Empire from Ottoman and French intrusions, while overseeing its expansion to the American continent. By the end of his life, he had established “an empire on which the sun never sets”—the first of its kind in all of human history.

Charles V was the most powerful monarch of his age. His ascent brought the Habsburg dynasty to the Spanish throne; his progeny ruled over the country and a large part of the world for the next century and a half. It was an era of wealth and well-being, an age of prosperity and plenteousness. However, due to several factors, including economic problems, political instabilities, and religious conflicts, by 1661—when Charles II was born—Spain was no longer the dominant great power of the continent.

In fact, by then, the issue of who would succeed him to the throne had already become a matter of diplomatic debate. Therefore, as soon as Charles II was born, his death became one of the most anticipated events in Europe. It didn’t help that he was struggling with poor health pretty much from the day he was born.

A brief study in royal inbreeding (and the risks of a shallow gene pool)

It is a known fact that, from the early Medieval era forward, European nobility frequently married within the same extended family to preserve status and possessions. Even among them, the Spanish Habsburgs deserve a special mention—arguably, they were the European royal dynasty most famous by the extent to which they followed the policy of consanguineous unions and imperial intermarriage.

It could be argued that this was a consequence of the limpieza de sangre (“blood purity”) statutes, which were developed on the Iberian Peninsula after the Reconquista so as to keep Christian bloodlines pure, while preventing anyone with Jewish or Muslim ancestry from marrying into an Old Spanish or aristocratic family. The statutes were eventually repealed, but by then the damage had been done. The Habsburgs had intermarried for centuries, and this led to the development of the Habsburg jaw, a physical deformity caused by inbreeding. Rather than being considered a handicap, the deformity became a symbol of the power of the Habsburgs, as well as their isolation from the rest of the world.

Charles II of Spain was born with an especially prominent Habsburg jaw. Most of his ancestors had intermarried; his parents were no exception. He was the only surviving son of Philip IV of Spain—who died when Charles was just three years old—and his very own niece, Maria Anna of Austria! It was one of two avunculate marriages (uncle/niece) in the royal history of Habsburg Spain; the other one was between Charles II’s great-grandparents, Anna of Austria and Philip II of Spain, one of the earliest Spanish kings to be born with a Habsburg jaw. His son Philip III (Charles II’s grandfather) had the same prominent jaw as well—and married his cousin! Charles II didn’t really have a chance.

The many deformities and diseases of Charles II of Spain

The deformities of Charles II have been well documented: many wrote about them throughout the latter half of the seventeenth century. We know, for example, that because of his prominent jaw, he couldn’t properly chew his food, which often caused him stomach problems. As a result of related genetic disorders—not necessarily brought about by the inbreeding—he struggled with prolonged infancy, as well as significant motor development issues. Probably due to Vitamin D deficiency, he suffered from rickets as a child: until the age of five, he couldn’t walk without the use of leg braces. Miraculously, he also survived several potentially deadly attacks of chickenpox, rubella, smallpox and measles—which had killed some of his siblings and relatives. In other words, he was a lot tougher than has been given credit for.

Due to his numerous diseases and ailments—and especially due to his extraordinary ability to somehow outlast them—Charles II (or Carlos II as he was locally known) was nicknamed El Hechizado, “The Bewitched One.” However, it seems that some of the reports of his deformities and ill health have been greatly exaggerated. For example, it’s not true that he was mentally retarded or that he was illiterate late into his teens; just as well, he didn’t really have a large tongue, so large it is sometimes said, that he could barely speak. But this is all just 17th-century sensationalism.

The truth is that Charles II was a victim of contemporary negative press. After all, there were many powerful people vying for the throne of Spain who couldn’t wait for him to die—and he repeatedly didn’t! Just an illustration. In 1687, when Charles II was 25, Francesco Niccolini, the Apostolic Nuncio to Portugal, famously described him as “short” and “ugly of face,” incapable of straightening his body (of which he says was “as weak as his mind”), “clumsy and indolent, constantly appearing stupefied,” and lacking any own will. Yet, we know that Charles II was a dedicated hunter and successfully negotiated the exchange of prisoners on more than one occasion. So, in truth, he was neither as useless nor as ill as it is generally accepted.

Rewriting history: Charles II and his Empire at the end of the Decadence

Charles II of Spain was a decent monarch. The reason why he isn’t remembered as one is because he inherited a splintered land, a vast empire in terminal decline. Even though the Spanish Empire was still the largest country in the world at the time he became a king, it had been in a state of unceasing decline for decades, with his father Philip IV declaring bankruptcy four different times over the course of his last twenty years as a ruler. So, whereas most of Charles II’s predecessors could worry about enlarging and enriching the empire, Charles II—a young man prone to illness, of no allies or male heirs—was left with the ungrateful task of managing its decline.

A large part of the decline was due to the Spanish-Franco War, which lasted from 1635 to 1659. The war was a disaster for Spain, as it lost a few of its colonies and much of its prestige, at the same time as catapulting France to European predominance. With the Sun King, Louis XIV, increasingly interested in the Spanish throne—and the Dutch Republic and England steadily becoming global economic juggernauts—the Spanish economy began to show signs of exhaustion. In an attempt to reduce the raging inflation, in the years before Charles II became a king, Spanish officials tried revaluing the Spanish coinage. The revaluation was not entirely successful: it led to a credit crisis and a total disruption of commerce, while failing to make Spanish exports more competitive and decreasing the people’s purchasing power.

Further problems were brought about by the so-called “Little Ice Age” of 1650-1700. Notwithstanding that the whole of Europe had to deal with it, Spain was especially affected. Poor harvests led to widespread starvation, and the population of mainland Spain dropped by 1.9 million people (or over 25%) in less than a single century—from 8.5 million in 1600 to 6.6 million in 1680! These were issues that Charles II of Spain was not the cause of, nor could provide any solutions for. He was, simply put, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, fighting a wrong war, and with all the wrong enemies.

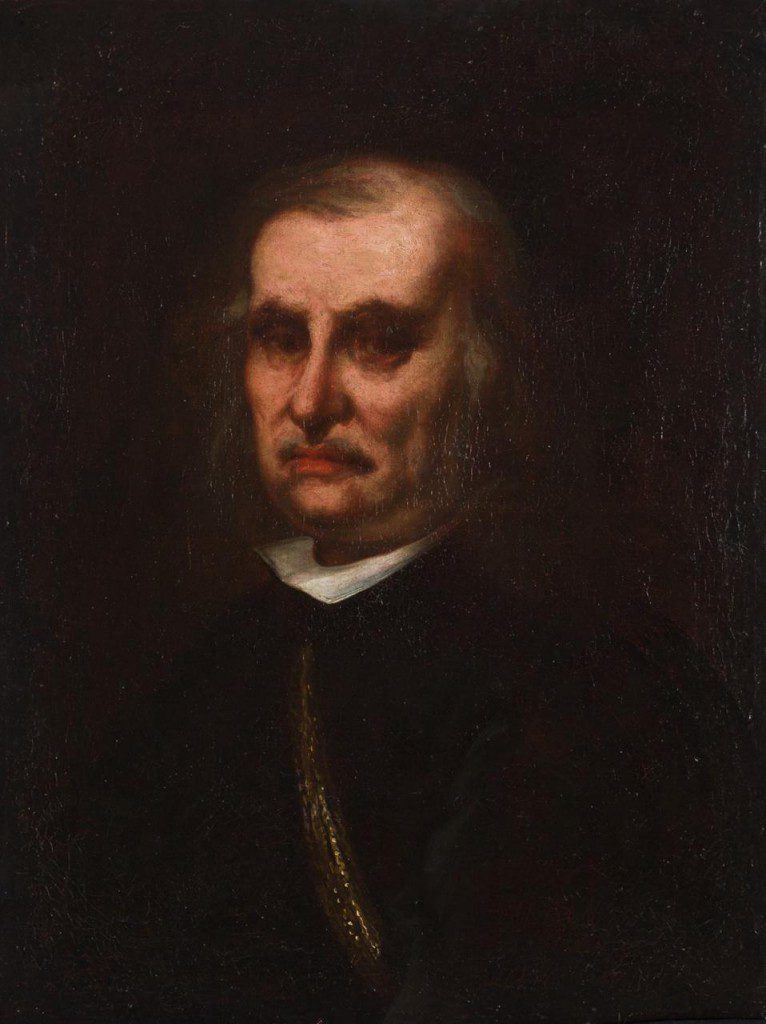

Even so, he largely succeeded in maintaining the territorial integrity of his empire, while overseeing the demographic recovery of mainland Spain, and instituting some of the earliest policies aimed at reforming peninsula trade. In addition, he was a great patron of the arts and sciences. An admirer of the work of Juan Carreño de Miranda—known today as “the painter of the Austrian decadence of Spain”—Charles II made him a court artist, and commissioned many paintings from him, including several portraits of himself and his wives, as well as two of Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, an extremely obese 6-year-old child. Combining Velázquezian gravity and decorum with the dark, loose vividness of Anthony Van Dyck’s technique, most of these portraits—as well as a few other paintings by Juan Carreño de Miranda—are nowadays considered supreme masterpieces of middle-Baroque art.

Childless Charles, Heirless Habsburgs

So, for all intents and purposes, it would be an exaggeration to say that Charles II of Spain was a bad monarch. The truth is, even if he was, he was certainly not particularly worse than those before him. In terms of his royal legacy, the main issue with him was, well, his issue: he couldn’t have any. His first wife, Marie Louise d’Orléans, struggled to conceive, and though we don’t know the reason for this, we do know that she once confided to the French ambassador in Spain that “she was really not a virgin any longer, but that as far as she could figure things, she believed she would never have children.”

It seems that Charles II blamed himself for this. At the advice of either his mother or governess (both named Maria Anna), he spent a period of his life sleeping next to his father’s grave, and then even alongside Philip IV’s disinterred body; it was believed, at the time, that this should help a person produce an heir. It didn’t, of course. Unfortunately, similar primitive fertility gave Marie Louise severe intestinal problem and in 1689—a decade after she had become the Queen of Spain—she died at the age of 26, probably from appendicitis.

After Marie Louise’s death, Charles II married Maria Anna of Neuburg. She was chosen precisely because her family had boasted reputation for fertility for several generations; Maria Anna herself was the last of 12 children. Even so, much like her predecessor, she was also incapable of producing an heir for Charles II. His autopsy, years later, would reveal that every hope to the contrary was futile all along: at the time he died, Charles II had a single atrophied testicle, black as coal.

The War of the Spanish Succession

It wasn’t only his impotence that the autopsy of Charles II revealed. It also exposed the extent to which he had been exhausted by his numerous afflictions and chronic health problems. The records say that his “heart was the size of a peppercorn;” that “his lungs were corroded;” that “his intestines were rotten and gangrenous;” and that “his head—was full of water.”

Charles died on November 1, 1700, in his royal palace, five days before his 39th birthday. In March of that year, he had chosen for his successor an Austrian claimant to the throne: Charles VI, a member of the House of Habsburg. However, just a few days before Charles II’s death, the Archbishop of Toledo, Luis Manuel Fernández de Portocarrero, coaxed him into altering his final will and testament in favor of another candidate: Philip of Anjou, the grandson of the French King Louis XIV. Philip was proclaimed King of Spain just 15 days after Charles’ death. The event set off the War of the Spanish Succession.

The war lasted for 13 years and resulted in the Bourbon Dynasty taking over the Spanish throne from the Austrian Habsburgs. In 1714, Philip of Anjou became Philip V, King of Spain; his descendants ruled Spain for the next century, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded the country and installed his own brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as the new king.

The War of the Spanish Succession had lasting effects on Europe, particularly in terms of the balance of power between the major states. It ended with a power shift; it began with a power struggle. However, its real origins should be sought elsewhere—most befittingly, in the bedrooms of the Habsburg royal family.