It is ultimately a tragic story, that of Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, an eternal child of six. Strangely enough, it begins not with her birth, as most personal stories do; rather, it begins with an unfortunate fascination: that of most European renaissance courts with the peculiar and the eccentric. In fact, it could be argued that the two surviving portraits of Vallejo—which today hang together in the Museo del Prado in Madrid—are the culmination of a century-long obsession of Spanish royals with odd-looking and disabled lowborns—and all for mere sport and prestige.

Dubbed la Monstrua, “the Monster,” Vallejo was summoned, as a confused six-year-old girl, to the court of Spanish regent Charles II, for no other reason than to fulfill the functions of a jester—that is to say, to serve as just another joke for the pleasure of the elite classes. Regrettably, the only quality of Vallejo that lent itself to such misuse and abuse was a severe genetic condition: perhaps due to a loss of function of specific genes on chromosome 15, she was of significantly larger stature than other toddlers of the time—and constantly hungry!

Never paid by the royal court for being maltreated, and immortalized by its painter for all the wrong reasons, Martínez Vallejo died a poor girl, in obscurity, at the tender age of 25. The least we owe her are a few paragraphs of sensitive remembrance.

Eugenia Martínez Vallejo’s childhood

Eugenia Martínez Vallejo was born in the small village of Merindad de Montija, one Sunday morning in 1674, during mass. Her parents, Antonia de la Bodega and José Martínez Vallejo, were relatively poor, but absolutely happy with the unexpected church birth. This was such a rare occurrence in 17th-century Spain that it was seen as a most fortuitous sign. That’s precisely how Eugenia’s voracious appetite as a toddler was also perceived: at the time, women of size were favored by the average man, as they were considered to be both more fertile and more beautiful.

It wasn’t long, however, before Eugenia’s parents realized that something was a bit off with their daughter. Just a year and a few days old, she was measured as weighing more than 50 pounds (around 25 kg), and a few months before she reached the age of six, her weight was reported as standing at staggering 150 pounds (68 kg)—which was the average weight of an adult Spanish man at the time! It was then, in 1680, that the news of her condition reached Madrid, and Martínez Vallejo was quickly summoned to the the Royal Alcázar, where queer individuals had been invited for decades—to be gawked at, toyed around with, to serve as mere jesters and fools.

Post mortem diagnoses: Eugenia’s disease

What nobody at the Royal Alcázar could have known for a fact back in 1680 was that many of the jesters at the court were actually disabled people, suffering from grave mental and physical disorders. Martínez Vallejo was no exception. In 1941, three and a half centuries after Eugenia’s death, Spanish polymath Gregorio Marañón hypothesized that she represented the earliest known case of hypercorticism, better known today as Cushing’s disease. One of the leading causes of the incurable Cushing’s syndrome, this rare disease is characterized by the overproduction of cortisol and can lead to a number of serious health problems, including high blood pressure, diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Modern research has all but disproved Marañón’s hypothesis and concluded that Martínez Vallejo’s extraordinary size was probably the result of something even rarer: the Prader–Willi Syndrome (PWS). Caused by a defect on chromosome 15, PWS is a genetic disorder characterized by mental retardation, short stature, low muscle tone, and a unique facial appearance. Just as prominently, individuals with PWS have an insatiable appetite, which can lead to constant hunger, compulsive overeating and obesity—the exact reason why Martínez Vallejo seemed so interesting to Charles II. Even though, quite ironically, he’s nowadays best remembered for his ill health and physical disabilities, the regent saw something monstrous in Eugenia, which fascinated him so much that he had his court artist paint two large portraits of her, one clothed and one nude.

The court painter and his model: Juan Carreño de Miranda and his two paintings of Eugenia Martinez Vallejo

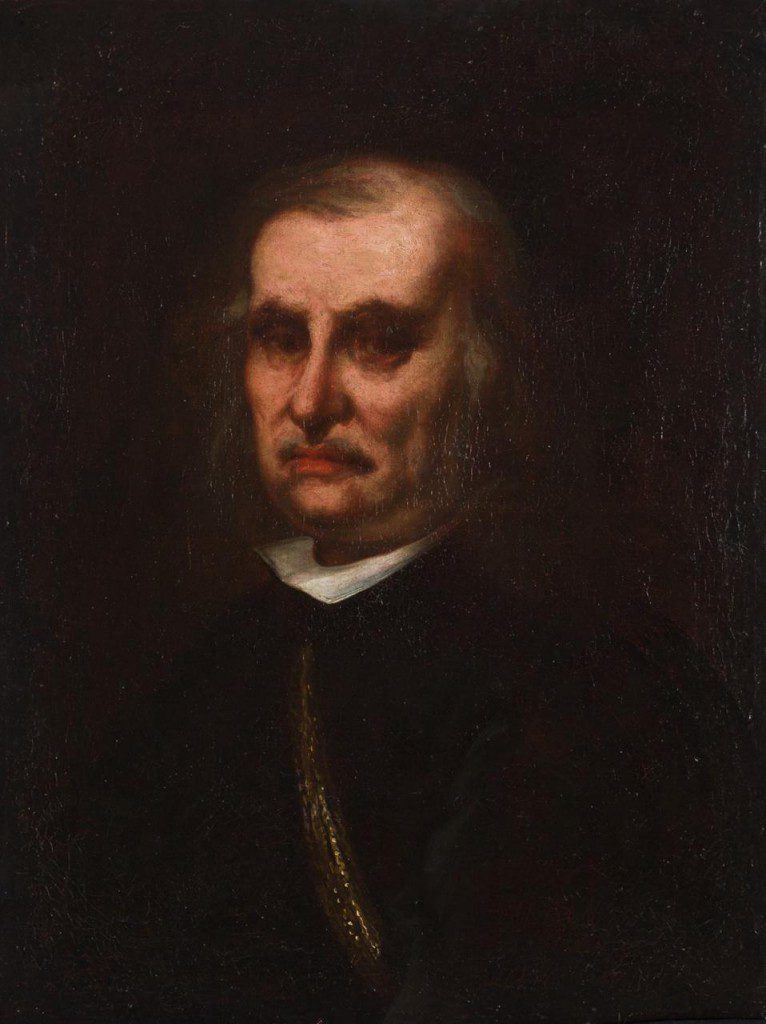

For the latter two thirds of his life, Baroque maestro Diego Velázquez was a court portraitist. For the first one of these two thirds, he was the darling-artist of King Philip IV, and then from 1640 to his death in 1660, he was the leading painter at the court of Charles II. After Velázquez died, there were only a few men in Europe worthy enough to take his place. Juan Carreño de Miranda, a proud Asturian, was one of them. Almost as soon as he was appointed court painter, he proved himself worthy of continuing Velázquez’ depiction of “monsters, jesters, and dwarves that inhabited the Spanish court.” So, unsurprisingly, his are the only two portraits of Eugenia Martínez Vallejo surviving today.

Portrait No. 1: La monstrua, clothed in finery

Not long after Eugenia’s arrival in Madrid in 1680, one Juan Cabezas published a booklet titled Relación verdadera (True Relation), in which he spent some time describing that “great prodigy of nature that has arrived at the court, in the person of a giant girl-child called Eugenia.” It is from Cabezas’ little book that we learn that, for Eugenia’s first portrait, the regent himself “ordered that she be attired decorously, in the style of the palace, in a sumptuous dress with red and white brocade and silver buttons.”

Even so, she looks quite desperate, as though uncomfortable and irate. In her left hand, she holds an apple, its color matching that of her dress, and symbolizing wealth and wellbeing, two things she’d never have. At the same time, the apple is hinting at Eugenia’s fall from grace. As late as the 19th century, physical disabilities were commonly viewed as signs of moral impairment. Since Eugenia was still a child, her sins were seen as being inherited by birth, going all the way back to Eve’s original fall.

Portrait No. 2: La monstrua, nude

In Carreño de Miranda’s second painting, Martínez Vallejo is portrayed entirely naked. Despite the disturbing nature of the act—a six-year-old child being presented for a nude portrait—there is a demonstrable improvement in Martínez Vallejo’s demeanor. Even if still perplexed, Eugenia seems a bit more comfortable, not the least because of Carreño’s ingenious decision to portray her as something more than just another freak—namely, a Roman god.

This time, instead of an apple, Eugenia holds a bunch of grapes in her left hand, the leaves of which cover her privates and hide her sex. She leans on a pedestal, laden with several fruits; one can still see the “apple of the fall” there, but it’s now hidden in the background, as if suddenly inessential or ignorable. What’s not is certainly her intricate crown of ivy and grape vines, which is what Bacchus, the ancient god of the grape-harvest and fertility, usually wears in painterly depictions. It’s almost as if she’s not Eugenia the Monster anymore, but Bacchus, the god, as a child.

Eugenia’s death and afterlife

By mythologizing Eugenia as Bacchus, Carreño de Miranda inadvertently did something no member of the Spanish aristocracy had done before: he humanized the young girl. One could even argue that, in some ways, his nude portrait questions the morality of his clothed version, painted as such on the strict orders of the king. It’s almost as if the artist realized something as an afterthought, as if he wanted to say out loud, if only through dark colors and subtle symbols, “Yes, she’s different, alright, but how can we be sure that she is something less than us? Maybe—just maybe—she’s something more?”

It was a question nobody actually bothered with in 1680. Vallejo was never compensated for her time at the royal palace. She was returned to her parents shortly after her portraits were completed, and brought in back only for certain events, as entertainment. Due to the lack of contemporary accounts, we know little of what happened next. But we do know that Eugenia died in poverty, completely forgotten by everyone, at the early age of 25—just one year before the death of Charles II kickstarted the War of the Spanish Succession. Perhaps she died traumatized and haunted by her very own portraits; or perhaps, just before she died—at least for a brief moment—she found solace in the knowledge that, for a few days in 1680, when she was just six years old, a royal portraitist saw her as something more than a freak, and shared his vision with posterity.