When you think of medieval knights, the image that no doubt springs to mind is that of the knight in shining armor, riding to the Crusades, or rescuing damsels in distress. However, those damsels may themselves have been members of a knighthood! In several European countries, there is evidence of female knights in the Middle Ages.

Knights in medieval times

The knight was the core of the medieval army. While early knights may have risen from humble origins, by 1200 AD, a knight was usually born into a noble family and trained in the arts of war from an early age. In a time when common soldiers fought on foot, a knight was part of the elite mounted force of the king’s army, wielding shields, swords, and lances as they pressed across a battlefield.

A knight swore an oath of allegiance to a feudal lord or the king of the realm and was often given land in exchange for their service. Their titles were not hereditary; the son of a knight would have to earn his title himself. However, nobles and princes were also knighted, as they were expected to fight for the king.

Women knights

Undoubtedly, the most famous woman soldier of the Middle Ages is Joan of Arc, who dressed in armor and rode a horse astride as she carried her banner and led the French armies against the English occupiers of France in the early 1400s. She never was knighted and, in fact, probably never raised a weapon against the English.

However, other women did take up arms against their enemies and were either formally knighted or informally considered knights. For most women, though, membership in a noble order was an honorary title rather than acknowledging actual participation in battle.

Women in the military orders

There were several different religious orders that, rather than serving the Church in prayer and good works, fought against the enemies of their religion. The most famous military order is certainly the Knights Templar, which along with the Knights Hospitaller, Order of the Holy Sepulchre, Teutonic Order, and the Order of Saint Lazarus, traveled to the Holy Land and battled the Muslims to capture the lands of the Middle East for Christianity.

It’s not commonly known that there were, in fact, women members of these military orders, but women played a role in several of these monastic orders, even if they weren’t taking to the battlefield on horseback. Some of them had separate religious houses for female adherents, although, by 1300, only the Hospitallers and the Order of Santiago still had convents.

Mostly, women who joined a military order served as nursing sisters or worked the land if they were of humble origin. Women from noble families were more likely to administer the lands donated to their order or engage in outreach to encourage others to join.

For instance, the Knights Templar had some rich women of high rank who were known as donatas; they turned over some of their wealth and, in return, were accepted as members of their local Templar chapter. However, there was only one Templar convent at Muhlen in Austria.

England’s Order of the Garter

The Order of the Garter is the most prestigious of the knightly orders of England, founded in 1348 by Edward III. Originally, the membership was limited to the king and his eldest son, with 24 Knight Companions, and was largely ceremonial.

In 1358 the membership was expanded to include some female knights, starting with Edward III’s wife, Philippa of Hainault. They were known as Ladies of the Garter and were often female members of the royal family, but not always. They were issued robes and hoods similar to those given to the Knight Companions, and at least some of them were granted the right to wear the Garter itself.

The Ladies of the Garter ceased to exist after Henry VII’s reign, only being restored in 1901 under Edward VII.

Italy’s Order of the Glorious Saint Mary

The story of this medieval order is hard to track, as very few sources reference it. In 1261, Loderigo d’Andalo, a nobleman of Bologna, founded the Order of the Glorious Saint Mary. This was the first order to bestow the rank of militissa on women. It received the approval of Pope Alexander IV, but almost 300 years later, Pope Sixtus V moved to suppress the order.

We have no record of what activities the women knights in this religious order actually engaged in; the order was supposed to work to bring peace to the Lombardy region, which was at that time wracked with civil strife.

Order of the Ermine

In 1379, John V, the Duke of Brittany, returned from exile in England and two years later established a new chivalric order similar to the Order of the Garter, the noble order of which he had been made a member during his time in England. Named the Order of the Ermine for the national emblem of Brittany, noblemen, women, and commoners were inducted into the order to recognize their service to Brittany.

France and the low countries

In France, women married to knights were called chevaleresses, the female equivalent of chevalier, the title for a male knight. However, there were cases where a woman held a fiefdom in her own right and was also given the title. In most cases, a female knight was the only daughter of the previous vassal or possibly female knights who would have inherited the family estate from dead husbands.

There’s no evidence that these women participated as warriors; their knightly duties probably only extended to contributing soldiers to their feudal lord’s forces and paying part of the fief’s profits to the overlord.

Meanwhile, in the Low Countries, convents for noblewomen were established in the mid-15th century. The women who entered these orders were given the title of chevaliere or equitissa, with a knighting ceremony using a sword.

Spain’s Order of the Hatchet

The Order of the Hatchet is the most concrete example we have of women participating in actual fighting and being recognized as knights during the medieval period.

Over the course of much of the Middle Ages, Spain was occupied by the Moors, while the Spaniards fought back against this foreign occupation. In 1148, Tortosa was captured by the Count of Barcelona, but the Moors laid siege to the city the next year. Count Ramon Berenguer could not fight back, and surrender seemed imminent. But the women, “to prevent the disaster threatening their City, themselves, and Children, put on men’s Clothes, and by a resolute sally, forced the Moors to raise the Siege,” saved the day.

As a result of their heroism, the Count established the Order of the Hatchet in 1149. The women who had fought to defend Tortosa were exempted from taxes, given precedence over men at public meetings, and given crimson badges in the shape of a torch.

Not knights, but definitely women warriors

In the Middle Ages, knighthood was a formal title earned only after a period of intensive training and serving as a knight’s squire and then bestowed upon a successful candidate in a ceremony.

In such a male-dominated age, it’s little wonder that there are so few female knights, but we do have some examples of women who demonstrated many of the qualities we associate with their male counterparts.

While in some cases, queens or other women of high nobility were fighting for their own right to rule a kingdom or duchy, others were fighting on their son’s behalf.

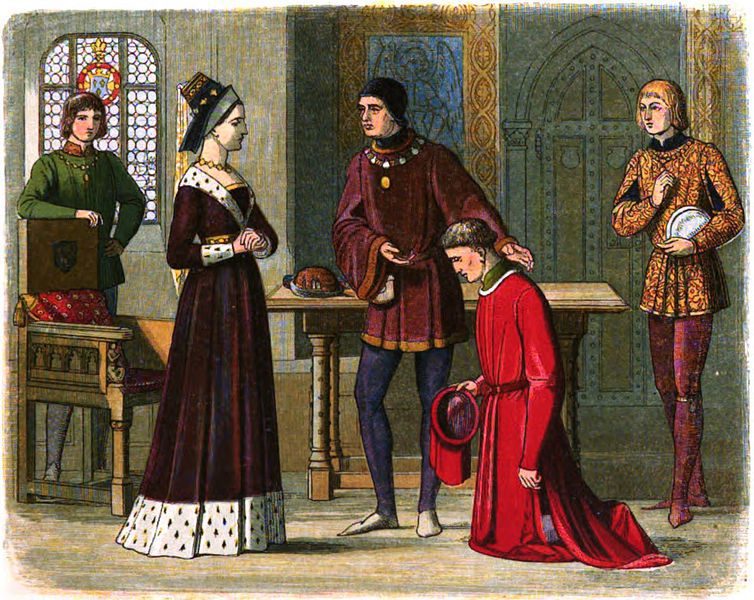

Matilda, the daughter of Henry 1, led an invasion force against her cousin Stephen when he claimed the throne after her father’s death. She claimed to be queen in her own right. The Anarchy, as the civil war was known, lasted from 1139 to 1153. Matilda was an integral part of the campaign against Stephen during the early years, although she did not actually fight in battle.

In 1217, Nicola de la Haye commanded the defense of Lincoln Castle while besieged by the forces of rebel barons and Prince Louis of France for seven months.

According to several accounts, one woman who wore armor and fought was Sikelgaita of Salerno in the 11th century. She fought by the side of her husband, Duke Robert Guiscard of Apulia, taking up arms in a battle against the army of Byzantium, and personally led the siege of the city of Trani against her own brother.

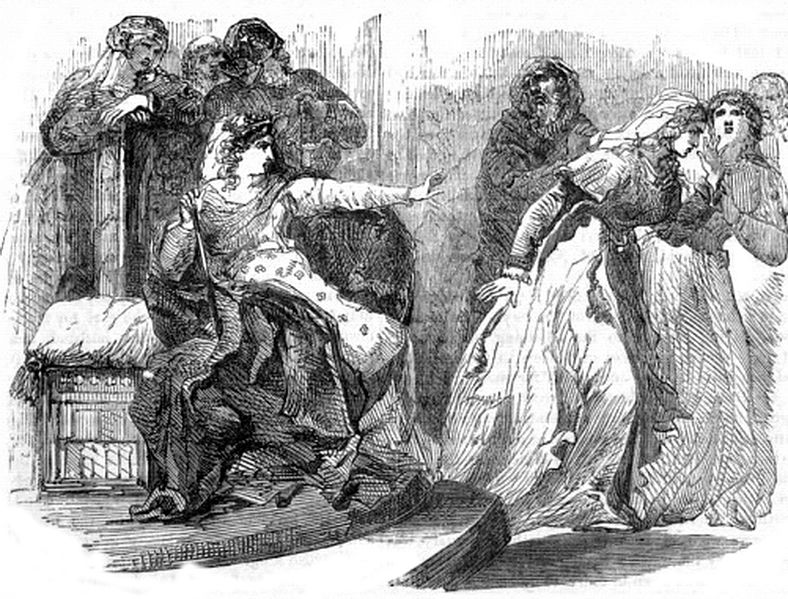

In the 15th Century, Margaret of Anjou, the wife of King Henry VI, commanded troops fighting for first her husband and then her son Edward’s right to the throne of England. Queen Margaret was considered a ruthless adversary; when her forces captured the Duke of York and his second son, she ordered them beheaded and their heads impaled on spikes outside the walls of York. Margaret would not surrender until after the death of Edward when all her hopes were crushed.

Women in the Middle Ages usually could expect their lives to follow a few well-defined paths; noblewomen were expected to marry early and bear heirs for their lord, while common women might work as servants or laborers whether they married or not. For many women, the only alternative was to join a holy order and spend their lives as nuns.

However, we have seen some examples of female knights in medieval times, whether they were defending a castle or land from attack or claiming a throne. Whether they were actually granted membership in chivalric orders or not, they demonstrated the same honor and courage as any armed man.