In William Faulkner’s short story, “A Rose for Emily,” the protagonist Emily Grierson—a Southern belle from a once-prominent family—lives a secluded life in her decaying mansion. As she descends into madness and delusion following the death of her domineering father, the townspeople become increasingly curious about her private life.

Only after Emily’s death do they uncover the gruesome secret she had been hiding for decades—the preserved corpse of her long-dead lover, Homer Barron, locked away in a room of her home. Bloodcurdling, the ending reveals a single strand of Emily’s iron-gray hair on the indented pillow next to Homer’s corpse, hinting at a disturbing and macabre relationship between the two.

The story of Elena Hoyos, a stunning Cuban beauty of everlasting 22, and Carl von Cosel, a German Jack-of-all-trades and self-proclaimed Count, is just as bizarre and chilling. Like Faulkner’s Gothic tale, it too involves a forbidden and grotesque love affair that ends in tragedy and scandal; unlike it, it’s hauntingly real.

Love at first X-ray: the German radiographer and the young señorita

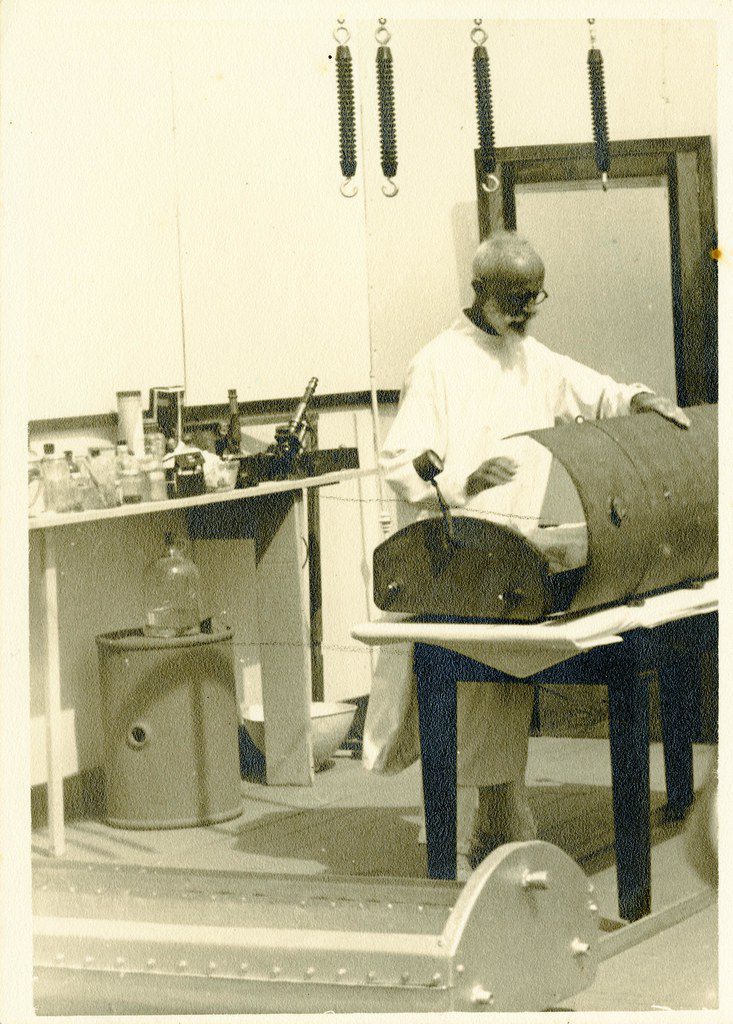

“A Rose for Emily” was first published in an issue of The Forum, on April 30, 1930. In a striking coincidence, just eight days before that, Count Carl von Cosel received a seemingly trivial phone call from the head office of the U.S. Marine Hospital in Key West, Florida, where he had been working for the previous couple of years as an X-ray technician.

The call informed him that “a young señorita,” an outpatient, had come for an examination, and that he was required to go immediately and take a blood test from her. Years later, in his unreliably dreamlike Memoirs—published under the Lovecraftian title “The Secret of Elena’s Tomb” in the September 1947 issue of the American pulp magazine Fantastic Adventures—von Cosel would describe his immediate infatuation with the young woman he met during that fateful exam:

The first thing I noticed of her personality as I bent down to take a drop of blood from one of her fingertips, rather than one of her ears which were too exquisitely lovely to mar, was that her hand was unusually small: its long tapering fingers the loveliest I had ever seen. […] Her face had been hidden by her hand, so that I had hardly seen it as I first entered the room. But now she withdrew her hand and I looked into a face of unearthly beauty, the face of the bride which had been promised to me by my ancestor forty years before.

The Ghost of Villa Cosel

According to von Cosel, it wasn’t just destiny that somehow led him from his birth town of Dresden, Germany, to Key West, Florida—it was also the caring ghost of his distant ancestor, Countess Anna Constantia von Brockdorff, a long-time mistress of Augustus the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony at the beginning of the 18th century. As attested by historical evidence, Augustus had once promised the Countess to marry her, but reneged on his word and abandoned her. After refusing to hand over Augustus’ secret written marriage promise, Anna Constantia was forced into exile in a remote castle in Stolpen, Saxony. Five decades later, just as the spring of 1765 blossomed, she passed away, heartbroken and alone.

If we are to believe him—and, admittedly, it’s often difficult to—Carl von Cosel spent much of his childhood in one of Anna Constantia’s villas, not far from Burg Stolpen, surrounded by stories of her tragic fate. Perhaps it was this family history, combined with his own eccentricities, that led Tanzler to become obsessed with death and the afterlife. Or perhaps, as he repeatedly claimed throughout his life, he was indeed visited by the ghost of his ancestor, if merely in a dream, when he was just a bleary-eyed 13-year-old boy, deeply absorbed in his experiments with electricity and flying machines. To quote him,

I was mysteriously awakened at around 2 A.M. I hardly believed my eyes. There were, however, standing by my bed two women, one bending over my face, a tall lady with snow-white hair, a striking likeness to the portrait of the Countess Anna which I remembered so well. The second figure kept somewhat behind her, as if trying to hide, and the Countess held the reluctant younger lady by the hand. Bending still lower and staring at me, the Countess Anna addressed me as follows: ‘… Look here, Carl, I have brought you the bride whom some day you will meet.’

When the younger woman’s veil briefly lifted, Carl saw a breathtakingly beautiful face framed by raven-black tresses. For a fleeting second, the girl smiled at him, captivating him with her radiance. Then, just as suddenly as she appeared, the woman vanished into thin air, leaving Carl bewildered, unable to speak or move. As brief as the encounter had been, the memory of the girl’s smile and beauty stayed with Carl Tanzer for almost 40 years. The moment he laid his eyes on “the young señorita” at the Key West Marine Hospital, he knew that he had already seen her before—she was the very same girl from his childhood vision.

Death is no way to die: the story of Elena de Hoyos

The birth name of the young señorita Carl Tanzler met on April 22, 1930, was Maria Elena Milagro de Hoyos, an exotic dark-haired woman of 21. Her father, Francisco “Pancho” Hoyos, was a local cigar maker, who had immigrated to Key West from Cuba years before, when the owners relocated the cigar factory he worked at to the Straits of Florida. Elena’s mother, Aurora Milagro, bore him two more daughters: Elena’s younger sister Celia, and her older sister, Florinda “Nana” Milagro. Sadly, both of them died of tuberculosis, in 1934 and 1944 respectively, as did Elena herself, on October 25, 1931, a year and a half after meeting Carl Tanzler.

It was Tanzler who first discovered the ignoble illness in Elena’s lungs. The blood tests showed nothing wrong, but a radiograph of the young woman’s chest revealed a dark mass that could only be tuberculosis. Tanzler was devastated by the news—it was a painful irony to bear, losing the girl of your dreams just after finally finding her in real life. Yes, tuberculosis is now commonly curable, but in the 1930s, a single droplet of blood in a person’s cough spelled a death warrant. Despite this, Tanzler was determined to save Elena. He offered to pay for her medical expenses, and even built a makeshift X-ray machine to monitor her progress. He spent countless hours by her side, administering various treatments and remedies, endeavoring to keep her alive.

“Carl, I think I’m dying,” Elena said one day, as Tanzler sat beside her, holding her hand. The words sent a chill down his spine—he knew them to be true, but he refused to accept them. “No, don’t believe that,” he stuttered at last. “You’re not going to heaven yet. But don’t worry: if you die, I’ll take you in my arms and—” “If I must die,” Elena interrupted, “all I can leave you is my body. For I am only a sick girl, so I can’t marry you while I am sick. But you will take care of my body after I die, won’t you?” Carl promised that he would. Little did Elena suspect this was a sacred promise, a marriage vow in all but name, and one that Tanzler would go to great lengths to fulfill.

The fanciful escapades of Carl Tanzler von Cosel

When Elena made Carl promise to take care of her body after death—provided that she did, of course, as we have only Carl’s unreliable memories to rely on—it was more than a simple request. To Carl, it was an inviolable oath, a pledge of love and devotion that bound them together for eternity. Their connection, he believed, was deeper than any earthly bond, and so, their marriage could only be spiritual. Not that it could be any different in practice—at the time of her death, Elena was still legally married to a fellow Cuban named Luis Mesa. Incapable of observing his marriage vows in full, Mesa may have cherished Elena in health, but abandoned her in sickness, shortly after the girl had been diagnosed with tuberculosis.

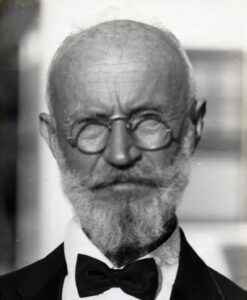

Carl Tanzler was married too, with two children—not that many people knew anything about it. Even in his memoirs, years later, he’d make no mention of his German family, remarking in passing that he, a bachelor on an Odyssey, “belonged to another years ago.” Meanwhile, his lawfully wedded Penelope—a hard-working woman named Doris Schäfer—was doing her best to raise their two daughters in Zephyrhills, Florida, where she was living at the house of Carl’s sister, a long-time immigrant to the United States. By the by, it is through Carl’s German marriage certificate that we find out another important thing about him—his birth name. Up until he changed it legally to Carl Tanzler von Cosel in his 70s, he was actually George Karl Tänzler, a fact that raises uncertainty about his claims to be descended from the noble von Cosel family.

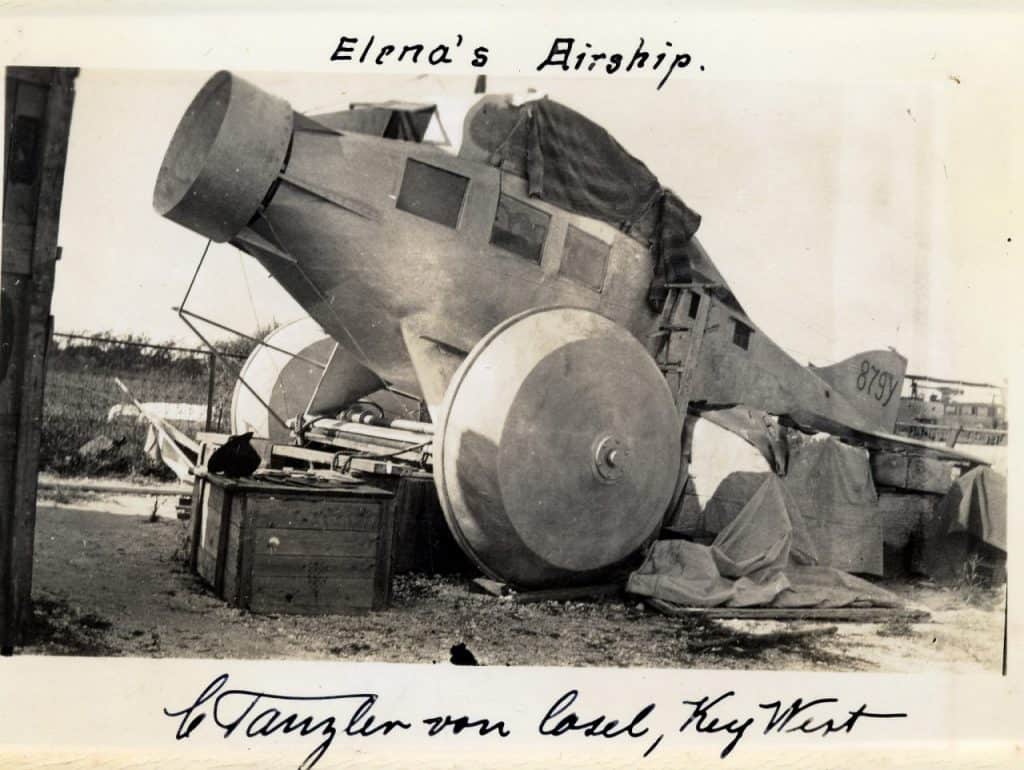

Either way, there was indeed a certain nobility to his character which cut a mesmerizing figure. With his dapper style and refined manners, Tanzler was often described as a gentleman by those who knew him. He was always impeccably dressed, carrying himself with an air of aristocracy, and possessed a deep knowledge of music and philosophy, as well as a talent for drawing. Newspapers of the day speak of him as “a man with nine college degrees,” a piece of information he didn’t fail to mention again in his memoirs. While this claim may seem far-fetched, it is nevertheless clear that he had a knack for understanding scientific language and using it credibly. After all, he did work as a radiologist, while his later endeavors demonstrate extensive training in chemistry. Moreover, though he’d never complete it, he spent years constructing himself a small airplane, possibly from scratch. He named it “Cts Elaine von Cosel C-3,” while Elena was still alive. He promised to one day fly her away to a far-off land where they could start a new life together. In some way, eventually, he did.

La boda negra

In Undying Love, Ben Harrison claims that “La Boda Negra” (“The Black Wedding”)—to the extent of our investigation, an 1885 bolero by Latin American romanticist Carlos Borges—was one of Elena de Hoyos’ favorite songs; soon enough, it probably became Carl’s too. A popular song in 1920s Cuba, it tells the dark tale of a bereaved lover “whose luck did betray/ when death took his sweet love away.” This is how the song, translated into English, continues:

Every night he went to the cemetery,

in silence, sadness and gloom.

Whispered the townsfolk with mystery,

“He’s a dead man, escaped from his tomb…”One night, unadorned with stars,

he shattered the abandoned crypt,

he dug up the earth and, in his arms,

her stiff skeleton he gripped.And there, in the darkness dreary,

by the flame of a funeral candle,

the corpse of his love he did marry—

oh, how the church bells trembled!He bound the bare bones with ribbons.

He crowned the stiff skull with flowers.

He kissed her vile mouth, unbidden.

He spoke of his love for hours.And then, with the dawn descending,

he lay in her bed uncovered,

and fell in a dream never-ending,

in the embrace of his skeleton-lover.

Oscar Wilde wrote once that life imitates art far more than art imitates life. At least in the case of “The Black Wedding” and the story of Carl Tanzler and Elena de Hoyos, nothing can be closer to the truth—the song’s haunting lyrics seem to have been tailor-made for the bizarre events that would unfold at Key West cemetery, 18 months after the death of Elena Hoyos.

Elena Hoyos’ unforeseen afterlife

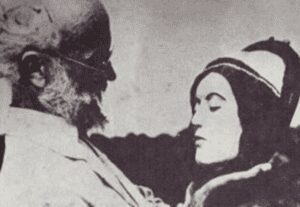

Ever since Carl Tanzler laid his eyes on Elena Hoyos, he became her devoted admirer, constantly finding ways to please her and fulfill her every wish. When Elena died, his obsession with her only intensified. Heartbroken and bereft, he could not bear to let go of her. Just when her coffin was about to be closed, he slipped a letter under her silk dress and onto her breast. “Elena, please come back to me, sweetheart,” it said. “I long so much for you, so tell me, what shall I do?” Since the de Hoyos were poor, it was Carl who paid for Elena’s funeral. Not long after, he offered them five dollars a month in rent money to live in Elena’s room; they needed the money so, as weird as it might sound, they accepted. “From then on, I slept in Elena’s bed,” Carl would later write in his memoirs. “It still preserved the sweet scent of her hair…”

With the permission of her family, Tanzler erected an above-ground mausoleum for Elena in the Key West Cemetery. Inscribed in the rectangle marble headstone were her name, the dates of her birth and death, and a curious little “Ct. d Cosel” in the lower right corner. True, this may have been a simple signature, but what did that “d” stand for, in that case? Is it possible, as Ben Harrison speculates, that this was Tanzler’s “obscure way of telling the world that Elena was now his wife—Countess damsel Cosel”? No doubt, that’s precisely how he treated her, even though she was dead. For 18 months, he visited the mausoleum he had built for her nightly, showering her corpse with gifts, serenading it with “La boda negra.” For 18 months, he continued to live in his delusion that Elena was somehow still alive, and that they were still together—even though, well, they never were.

One evening in April 1933, Tanzler took his obsession to an unimaginable level. Under the cover of darkness, he crept through the cemetery, removed Elena’s body from the mausoleum, and transported it, on a toy wagon, to the cabin of his plane. It was Elena’s spirit—he’d claim later in court—that had urged him to take her from the grave; he was merely following divine orders. Distressed at “the awful condition” of Elena’s body, he went to great lengths to spruce it up. He piano-wired the bones together and inserted glass eyes into the face. He filled the chest with rags, and replaced the skin with silk cloth soaked in wax and plaster. He dressed her in clean clothes, trinkets and all, and even fashioned a wig from her very own hair. To mask the odor of the decomposing corpse, he used perfumed soap and spirits of wine. He was exultant: “Despite the mud and slimy rags in which she had been lying for so many months, my angel was pure…”

The end of the affair

Tanzler moved Elena’s body to a tumbledown shack on Rest Beach; Mario Medina, husband of Elena’s sister Nana, helped him in the endeavor. Sitting atop Tanzler’s wingless airplane, as it was slowly being towed down the streets of Key West by a hired truck, Medina could have never guessed that he was part of such a macabre operation…

For over seven years, Tanzler shared his life with Elena’s lifeless body; these seven years, he’d maintain to the very end, were the happiest of his life, by far. They came to an abrupt end in the fall of 1940, when rumors of Tanzler sleeping with Elena’s body reached the ears of the disturbed Nana. On a fateful September 28 morning, Mario arrived at Tanzler’s home and informed him of Nana’s suspicion that Elena’s tomb had been tampered with. He returned three days later, and asked Tanzler to accompany him to the cemetery. There, Nana confronted him and demanded that the coffin be opened, causing a commotion amongst the onlookers.

“This shouldn’t be a public affair,” said the cornered, but nevertheless defiant, Carl. “If it’s Elena you want to see, then come with me. Come with me, Nana, and see how beautiful Elena is resting in her bed in her silken garments and with all her jewelry. Come and see, she could not have it better anywhere. I think that will pacify you now…”

It didn’t, of course—the unimaginable sight was so disturbing to Nana and Mario that they dashed off to the nearest police station almost immediately. Shortly after, a motorcade pulled up in front of von Cosel’s house, with two sheriffs leading the way, followed by the justice of the peace, a funeral car, and several other vehicles. As Elena’s corpse was taken to be reburied in an unmarked grave, in a secret location, Tanzler was handcuffed and charged with wantonly and maliciously destroying a grave. As he was taken to the courthouse, he cast one last look at Elena’s body. “Suffer it for me,” it seemed to him that she said. “It won’t be long. Then we will be free…”

The trial and death of Carl Von Cosel

When the story of Carl von Cosel and Elena de Hoyos hit the news in October 1940, it created a sensation that captured the attention of the entire country. People were both fascinated and horrified by the strange tale of the man who had lived with the corpse of the woman he loved for over seven years. The case became a media circus, with reporters and photographers from all over the United States descending on Key West to cover the story. von Cosel became a household name, and his strange obsession with Elena Hoyos became the subject of endless speculation and gossip.

Strangely enough, most people were generally sympathetic to the doctor, recognizing in him a refined romantic rather than a rogue. Mrs. Medina begged to differ. “He’s no idealist,” she told The Miami Herald on October 21, 1940. “Instead of being lauded, he should be condemned. I am convinced that the man was driven insane by his desire for Elena. He could not have her in life, so he stole her body and imaged her to the best of his ability. It is hard to conceive, but I am firmly convinced that his removal of the body was not motivated by a desire to restore life, but was the act of a man driven insane by his love for Elena….”

In the end, von Cosel was not charged with any crime, as the statute of limitations for the charges had expired. He left Key West a free man, moving to Zephyrhills first, and then to a rural residence of his own in Pasco County, Florida. It was there that he wrote his autobiography, in the cabin of Elena’s airship, “where her coffin had rested so long ago.” Even though he spent the rest of his life in relative obscurity, Count Carl von Cosel did make the headlines two more times: when his memoirs, edited and abridged, were finally published, in September 1946, and six years later, when his badly decomposed body was found by the police, on a quiet Wednesday morning, in the month of July 1952.

Officers searching his cluttered little house were met with a macabre sight. There, in the middle of the room, right next to Tanzler’s lifeless body, was a large object covered with a sheet. When they removed the sheet, they discovered that it was a life-sized effigy of Elena, decked with her death mask. Right to the very end, von Cosel had maintained his love for Elena, and kept his obsession alive. But, then again, it’s not like he even hid it. His memoirs end with a declaration of his undying love for Elena and his belief that they would be reunited in the afterlife:

Human jealousy and hatreds have robbed me of the body of my Elena. Yet Divine happiness is flowing through me. For she is with me. Nobody could take her away from me for God Almighty has united our souls. She has survived death, forever and ever she is with me…