“One’s death should be a memorable occasion,” writes Israeli-born writer Lavie Tidhar near the end of his “nicely affecting” short story “Vladimir Chong Chooses to Die,” one of the best SF-works of 2014. There’s a reason we start our article with this quote, and it’s not just because it’s a great line.

Vladimir Chong chooses to die

It’s Tel Aviv, the far future, and Vladimir Chong is an old man, tired of living several lives at once. Weiwei’s Curse is what the doctors call it, his curious affliction, after the name of his late father. As people get older, they tend to forget things. With Vlad, it’s the other way around: with each passing day, he seems to remember more and more about the past, inheriting ever newer memories from Weiwei, his family, his loved ones.

They come broken, though, the recollections, jumbled up to the point of disarray and incoherence. Vlad can remember his mother’s terminal illness and his father’s work injury, but not his own wife’s name. “Drowning under the weight of memories,” there’s only one thing he is absolutely certain of—that he is not afraid of death anymore. He can remember death. In fact, he can remember several deaths. It’s just that none of those are his. And it’s time to change that.

At the life termination clinic—fanned out, in its frighteningly cool calmness, across a pine-scented oasis in the heart of Central Station—Vlad is visited by his son Boris and his “80-percent cyborged” sister Tamara. The two try to talk him out of his determination to end his life, but it is to no avail. It’s only the method that Vlad is unsure about.

“We have a range of options available, of course,” Dr. Graff, the mortality consultant, politely tells Vlad, handing him a book-length catalog. “We, humans, are remarkably good at devising new ways to die.” Leafing through the book, Vlad brushes off the overly traditional “blood loss in a warm, scented bath” and the “garish faux-murder” before seeing something that catches his eye. “I’d like this,” he says, tapping the page with his finger. “The Euthanasia Coaster.”

Less than a human world, more than a human being: the HUMAN+ exhibition

Back to reality now, April 15, 2011. At Trinity College Dublin, the Science Gallery opens its newest flagship exhibition HUMAN+, inviting visitors to “consider a future of augmented abilities, authored evolution, new strategies for survival and non-human encounters.” Michael John Gorman, the Gallery’s director, describes the exhibition as “a combination of a sweet shop and a pharmacy, an Alice-in-Wonderland world of pills, promises and prosthetics.”

There’s a lot to see and mull over inside. A silver toolkit to help humans pollinate plants in the seemingly ineluctable post-bee world of tomorrow. Sixty skulls with mechanical eyes that follow you around while tracking your facial features. An Improvised Empathic Device, which pricks the wearer with a needle every time a US soldier dies overseas. A “plantimal flower” called Edunia which combines the DNA of a petunia with that of a human.

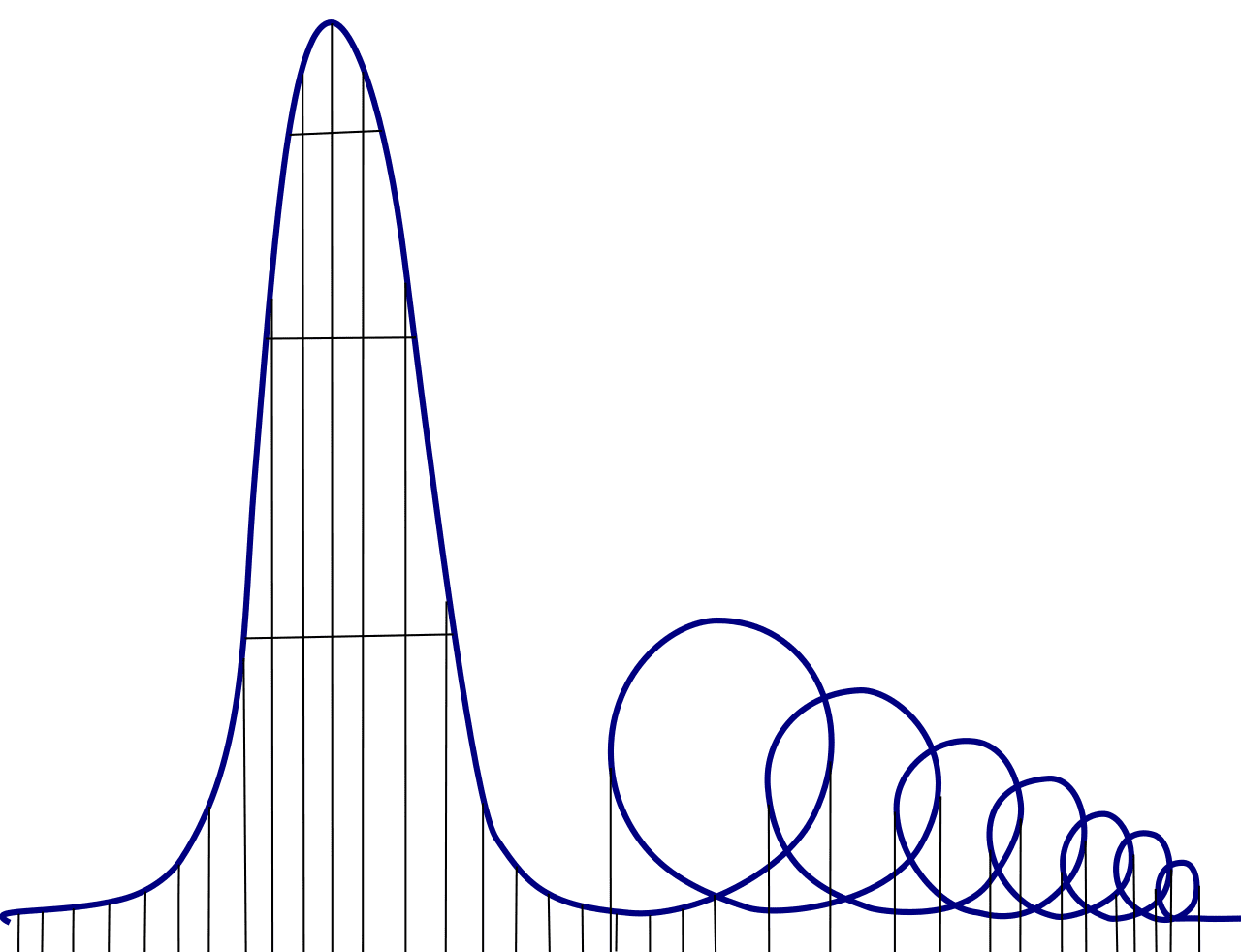

Still, the thing that attracts the most attention from the media is a 1:500 scale model of a steel roller coaster. It’s designed by Lithuanian artist Julijonas Urbonas, a PhD candidate at the Royal College of Art in London. It’s not only the name that makes Urbonas’ roller coaster so provocative—the Euthanasia Coaster—but also its intent. “The Euthanasia Coaster,” its description states, “is a hypothetic death machine in the form of a roller coaster, engineered to humanely—with elegance and euphoria—take the life of a human being.”

Before too long, these words would launch a thousand reports, retorts and virtual replications, a special TV show, a rock song, a short movie. They would also inspire a chapter in a 2022 novel, and Lavie Tidhar’s lauded short story, written just three years after the HUMAN+ exhibition. In April 2011, Michael Gorman saw, in Urbonas’s Euthanasia Coaster, an invitation to ponder over “the ultimate boredom of longevity.” Other artists saw something far more literal and, arguably, just as disquieting: a way to make death… different.

The death coaster experience

From 2003 to 2007, Julijonas Urbonas ran an amusement park in the coastal city of Klaipėda, Lithuania. There, he became fascinated with “gravitational aesthetics” and the idea of a concept roller coaster that would “celebrate the limits of the human body,” by allowing its riders to experience the dizzying effects of a fatal g-force. “The ultimate roller coaster is built when you send out 24 people and they all come back dead. This could be done, you know,” said once John Allen, former president of the celebrated Philadelphia Toboggan Company. It is in this quote that “the killer coaster” was born.

1. The lift: the most idyllic prelude to a most extreme ride

The euthanasia roller coaster begins with a slow, sharp-angled lift that carries riders up 1,600 ft (500 m) to the top of the drop-tower. As the ride is about 0.3 miles (0.5 km) long, it takes a while, no less than a couple of minutes. This is so by design: the idea is to give people a chance to go over their past lives once again, and reconsider their decision one last time.

2. The top: getting a bird’s eye view of life, death and everything

Sitting at the top of the Euthanasia Coaster, riders are given a few minutes to enjoy the view, say their goodbyes and possibly change their mind. If they do, they can just press a button that will abort their journey and let them off the coaster. If they don’t, they go ahead and press the “fall” button which will initiate the ride.

3. The fatal journey: surrendering to the inexorable force of gravity

Whirrr… swish. The 1,600 ft (500-meter) drop accelerates the coaster car to a whopping speed of 220 mph (360 km). It’s close to the terminal velocity, “when the force of air drag becomes equal to the force of gravity, thus cancelling the acceleration.” Just after, the coaster’s track flattens out and enters swiftly into the first of its seven 360-degree loops, all of which completely invert the riders at the topmost part. Each loop has a smaller diameter, and is engineered in such a way to ensure the deadly 10 g-force remains constant despite the train losing speed.

4. The cause of death: cerebral hypoxia

The loops are a fail-safe, to ensure the trip ends the riders’ life. Chances are, the drop will leave most of them either already dead or unconscious, rushing their blood to the lower extremities and causing oxygen deprivation in the brain. “It is exactly this cerebral suffocation, also known as cerebral hypoxia, that is going to kill you,” reasons Urbonas. But what if it doesn’t? What if you survive the drop conscious?

5. The before-effects: through 10 g to g-loc

If one is “g-force-resistant enough” to remain awake after the initial drop, they will experience several g-force related symptoms. First, their vision will blur. Then it will lose color (grayout) and peripheral sight (tunnel vision); finally, along with hearing, it will disappear completely (blackout). The experience—which may be “accompanied with disorientation, anxiety, confusion, and euphoria”—should cancel itself with G-LOC (g-force induced loss of consciousness), during which the body becomes completely limp as the mind drifts off in a world of bizarre and vivid dreams.

“Of course, you can tell the story only if you survive,” says Urbonas, “but that is virtually impossible.” That’s where fiction comes in handy.

Vladimir Chong, revisited

So, back to our dear friend Vlad, whom we left at the life termination clinic in Tel Aviv. After filling up the necessary forms, a solar-paneled mini-bus takes him and his loved ones to the Arava desert, wherein—”in a green oasis of calm”—lies the Euthanasia Park. Within it, just beyond the glinting-blue swimming pools and the needle-like towers, the Euthanasia Coaster stands erected, 1,600 ft (500 m) above the ground. Vlad says his goodbyes, sits down in the car and puts on the safety belt. At the top of the hill, just before he presses the “fall” button, he remembers his wife’s name. And then…

The car dropped. Vlad felt the gravity crushing him down, taking the air from his lungs. His heart beat the fastest it had ever beat, the blood rushed to his face. The wind howled in his ears, against his face. He dropped and levelled and for a moment air rushed in and he cried out in exultation. The car shot away from the drop and onto the first of the loops, carrying him with it, shot like a bullet at 358 kilometers an hour. Vlad was propelled through loop after loop faster than he could think; until at last the enormous gravity, thus generated, claimed him.