The Countess of Castiglione began life as Virginia Oldoini, a celebrated beauty and a member of the minor nobility in Florence, Tuscany. She was noted for her fair complexion, delicate oval face, long blonde hair, and eyes that changed color from blue-violet to green. Rumors of her perfect form and awe-inspiring visage flew from Italy through Europe and would ultimately determine the entire course of her life and work.

A noble wedding

Her adult life began when her beauty and noble blood allowed her to become the Countess da Castiglione through marriage to Francesco Verasis. She donned this title at the young age of 17, causing the men and women of the royal courts she subsequently frequented to know her primarily as La Castiglione.

On an early trip to Paris, she and her husband met with Camillo, Count of Cavour. He served in a political role as a minister of the King of Sardinia, who desired the unification of Italy. Knowing that Napoleon III was easy to seduce, he begged the Countess of Castiglione to plead the case for Italian unification to the emperor. Camillo encouraged seduction in no uncertain terms when he told her to succeed using any means necessary.

Seducing the last French Monarch

Gaining the attention of Napoleon III proved more difficult than expected. He commented that La Castiglione was a “dull doll,” implying that what she had in looks, she lacked in personality. Four months of attention-grabbing stunts were required for her to become Napoleon’s mistress. By that time, the Countess of Castiglione was as well-known for her detailed and decadent outfits as she was for her beauty.

Unfortunately, acquiring so many exceptional dresses, capes, and headpieces required lavish spending. By the time she gained notoriety as Napoleon III’s mistress, she had bankrupted her husband, who pushed for an irrevocable marital separation due to her infidelity and insupportable spending habits.

With the fruits of her husband’s fortune and her natural beauty, the Countess of Castiglione affected grandiose and eye-catching entrances. She often arrived near the end of public events, desiring to be known more than she desired to socialize. On one famous evening, Napoleon III was leaving as she was making her grand entrance, “You are too late,” he said. She replied in kind, “No, Sire. You are leaving too early.”

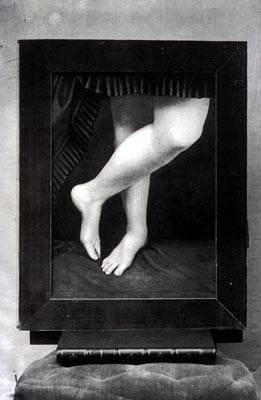

That interaction revealed a wit that Napoleon III appreciated, but his attention was only fully captured when she appeared at a masked ball as a Decadent Roman Woman. She revealed miles of porcelain legs and decorated her exposed toes with golden rings. With the conservative, almost prudish taboo the Victorians had against showing women’s legs, ankles, and feet, her outfit astonished partygoers while bringing her extraordinary beauty to the forefront.

Self obsessed influencer

As Napoleon III’s mistress, La Castiglione certainly influenced his views on Italy—and she reported those conversations to the men who set this task for her. But in the end, she would only be his mistress for less than a year, limiting her ability to manipulate him. It wasn’t boredom, but indiscretion which provoked Napoleon to discard her. When the Countess bragged and showed off the many gifts the emperor gave her, these lapses in her discretion prompted the dissolution of their relationship.

La Castiglione lived and died for beauty, but her inner beauty wasn’t up to the standards implied by her physical assets. While she was lauded as “Venus descended from Olympus,” she was exceptionally self-absorbed. Her arrogance was stupendous. It’s said that she expected to be admired by those who shared her company, and that her conversation was often grating, as it centered around herself and her needs exclusively.

In 1857, when her relationship with Napoleon III ended, La Castiglione moved back to Italy. While there, she was granted a pension for her diplomatic accomplishments. After four years in Italy, her political acumen was vindicated when the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed. She would later influence politics again when she was called to Otto von Bismarck’s side in a successful attempt to discourage his armies from occupying Paris.

Pioneering photography

But photography is the true legacy of La Castiglione’s life. By shooting and painting hundreds of photos to perfection, she opened the door to using photography as a medium to tell stories and create emotionally affecting art, ignoring its traditional usage of simple portraiture.

She paired with the imperial court photographers Mayer & Pierson from 1856 to 1895, utilizing the technology of painted photographs to craft multiple, sometimes conflicting, portraits of her nature. She sought to emulate her life, both as she lived it and as she imagined it. She also produced many photographs of herself depicting famous women from the Bible, history, and mythology.

Her level of control over these projects cannot be

understated; she did everything from choosing the camera angle to painting the photographs herself. Though most of the 700+ photos depicted her wearing her singularly extravagant outfits, some photos were salacious for the time, depicting her naked legs and feet. While many photos elevated her, her wardrobe, and the inventiveness of her spirit, other photos—especially those taken in her later years—were unsettling or macabre.

Once she even used this photographic art to communicate with others. When her husband threatened to obtain custody of their child, she replied by sending him a photograph of herself in her Queen of Etruria costume, pointing a knife at the viewer. The photo was entitled La Vengeance. Upon receipt of this photo, her husband quieted and left the boy with his mother.

The use of most of her photos is unclear. Some say she kept the corpus for herself, while others claim she offered albums to others as a sign of her favor or to control her public image and reputation.

In creating these photographs, the Countess cemented her place as a divine, unearthly beauty with a unique visual imprint on the royal courts and anyone knowledgeable about photography. A few of her admirers were fixated upon her beauty and art. Most famously, Robert de Montesquieu collected hundreds of her photographs and wrote a biography of her that he titled La Divine Comtesse.

Read more: Maria Rasputin: The Fascinating Life of the “Mad Monk’s” Daughter

Her last years were eccentric, but as in most of her endeavors, her youthful beauty drove her decisions. She lived in an apartment in the Place Vendôme where she painted the rooms entirely in black and banned mirrors. Within her abode, the blinds were always drawn against the sunlight, and it’s rumored that she only left her home at night. These actions protected her from watching her own beauty decay, and allowed her admirers to only remember the beauty she was in her youth. As an older woman robbed of the beauty that defined her, La Castiglione left the world quietly, in isolation and in darkness.