Pankration competitions, much like the UFC and MMA around the world today, were commonplace across ancient Greece. Such feats of bravery and violence were displayed as an Olympic event from 648 BC until the Christian Byzantine Emperor abolished the sport in 393 AD.

But what was Pankration? What part does it play in ancient Greek history? Who competed? What skills, moves, and regulations were involved in the battle? And most importantly, what role did it play in developing some of the world’s most significant sporting events, including the Olympic Games and mixed martial arts, until the dawn of modern Pankration?

What was Pankration?

Pankration was an ancient Greek martial art introduced to expand the original Olympic games’ fighting offering. The name comes from the Greek pan, meaning ‘all,’ and kratos, meaning ‘power.’ The name of the sport literally means to employ ‘all powers’ with the aim of victory over an opponent.

Pankration competitions filled a gap in the market of the ancient Olympic Games by offering an all-around fighting sporting event in which nothing, or almost nothing, was off-limits. Unlike the established boxing and wrestling, the precursor to MMA was performed with bare hands and nothing else.

As an athletic event, Pankration was at the forefront of ancient Greek culture, where Greeks believed it to be an essential part of a soldiers’ upbringing. The competitions combined many different moves derived from boxing and wrestling but also included kicking, chokes, and submission moves which would make it so familiar to modern MMA fans. However, the ferocity of Pankration competition would often result in the death of an opponent—which was nevertheless considered a victory.

Skills such as striking and grappling techniques were taught and practiced rigorously by Greek soldiers who wanted to participate in the sport to prove their mettle. The only two Pankration rules were no biting and no eye gouging. Athletes received punishment for aiming to gouge or ground and pound opponents’ private parts. However, the rule was seemingly enforced through the mutual respect of participants and officials rather than codified.

The history of Pankration and the Olympic Games

Pankration originated in the Greek and Roman antiquities, and whilst an Olympic event from 648 BC, it had been practiced potentially since the second millennium BC. The ‘Pankration event’ was a crowd favorite at the 33rd Olympic Games. As part of the ‘heavy events’ alongside wrestling and boxing, it was reserved only for the strongest athletes.

However, Pankration’s reception at the Olympics was not beloved by all—as many thinkers and philosophers of ancient Greece were damning in their criticism. Xenophanes suggested that the sport was a ‘terrible contest’ which served only to enrich those strong enough by gaining the adulation of fans. The competitors took pride in representing their city-state at each game and were well aware that they would return as heroes by being successful. Think gladiators in the Colesseum or a much more violent and ancient version of Love Island.

Pankration’s mythical origins

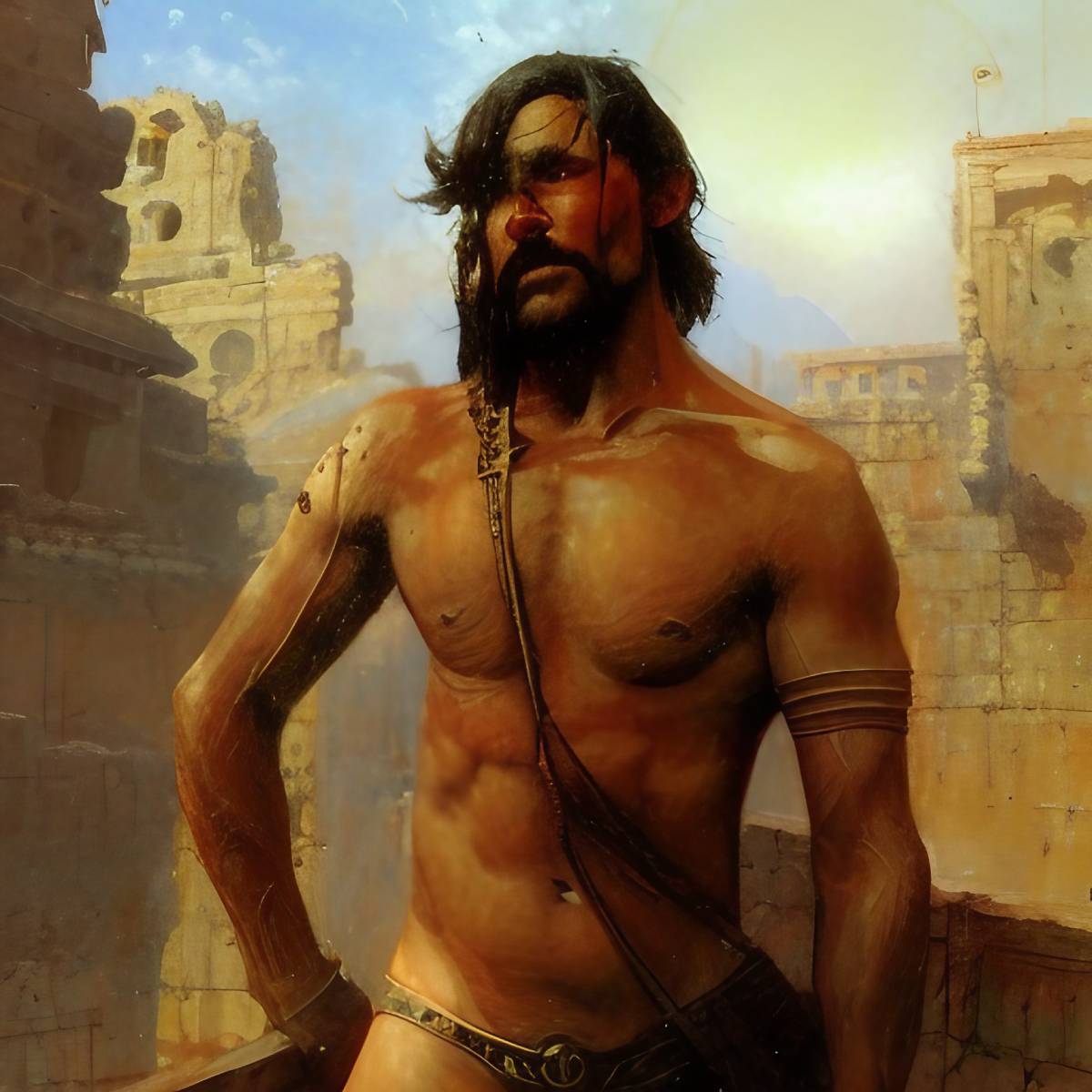

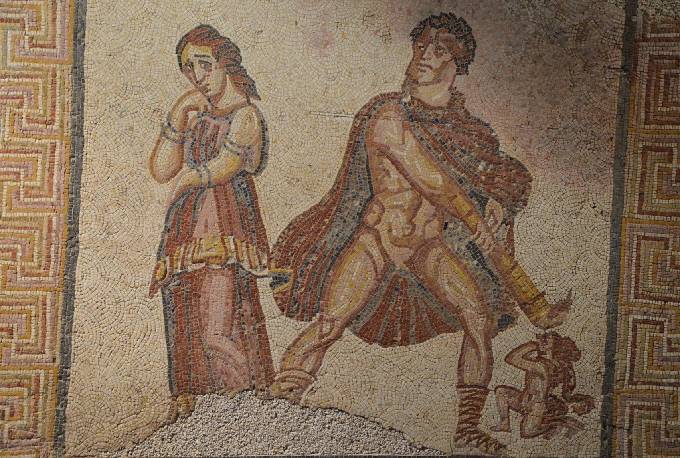

The nobility of Pankration is derived from mythology. It was said that Heracles and Theseus were the originators of the sport, with Theseus famously driving the Minotaur to submission in the Labyrinth using his prowess at grappling. Similarly, Heracles was said to have used Pankration techniques to victory against the Nemean lion—the defeat often depicted in ancient Greek art and culture.

However, Pankration was not merely a skill learned by the heroes of Greek mythos but was a strengthening exercise used in part of the soldierly activity. In particular, the Spartan hoplites and Alexander the Great’s Macedonian phalanx counted skilled Pankration fighters amongst their ranks. Ancient sources stated that at the famous last stand of Thermopylae (upon which the Gerard Butler-starring film, ‘300‘ was based)—after the spears and swords of the Spartans were rendered useless, the warriors continued fighting with their bare hands. Fortunately for the Spartans, the rules on gouging an opponent’s eyes were not enforced while in deadly combat.

Alexander the Great’s influence

The training that went into Pankration was so significant that it became a defining feature of a soldier’s prowess in the field, depending on his mastery of the art and techniques required. Herodotus mentions specifically that Hermolycus, son of Euthynus, was particularly distinguished in the battle of Mycale in 479 AD. Alexander the Great is on multiple occasions mentioned by ancient greek history as being a supporter and enabler of Pankration events around his court.

Famous pankratists such as Dioxippus, Arrhichion, and Theogenes were recognized as some of the most inspiring cases of bravery and regaled by ancient greek history for centuries. Dioxippus showed particular courage. After winning the Olympic Games in 336 BC, he went on an expedition to Asia, naturally falling into the inner circle of Alexander the Great. He was challenged by several of Alexander’s followers to duels, fighting only with his training and a club to hand. In contrast, Coragus, another famed warrior, fought with weapons and full armor. Dioxippus defeated Coragus without killing him, fighting and forcing his opponent to concede. However, Dioxippus had nothing on Theogenes—the man who allegedly won over 1300 bouts over a distinguished career—making him, probably, the best martial artist of all time.

Pankration techniques allegedly journeyed with Alexander the Great to India and beyond after his death, forming the basis of Asian martial arts. Pankration developed into many different practices, which we can still see today, that have become more specialized than the original bare hands’ event ever was.

Decline and ban of Pankration

From John Murray’s work, we know that by the time of the coronation of the first Roman Emperors and the dawn of the Imperial Period across the empire, the Romans had adopted the sport into their games in the colosseum as a part of gladiatorial combat. The usual regulations surrounding kicking, boxing, and wrestling on the ground were maintained from the ancient Greeks’ games.

However, the sport was to be short-lived, as, by 393 AD, Pankration and all other pagan festivals were abolished by an edict of the Christian Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I. The sport was almost entirely removed from the Greek English lexicon and forgotten in the annals of history.

What were the rules of Pankration?

There were two significant constraints to the sport, which hold similarities to modern-day MMA. First, there should be no eye gouging, and second, there should be no biting. However, the sport wasn’t as simple as throwing two men in the ring and waiting to see which came out on top.

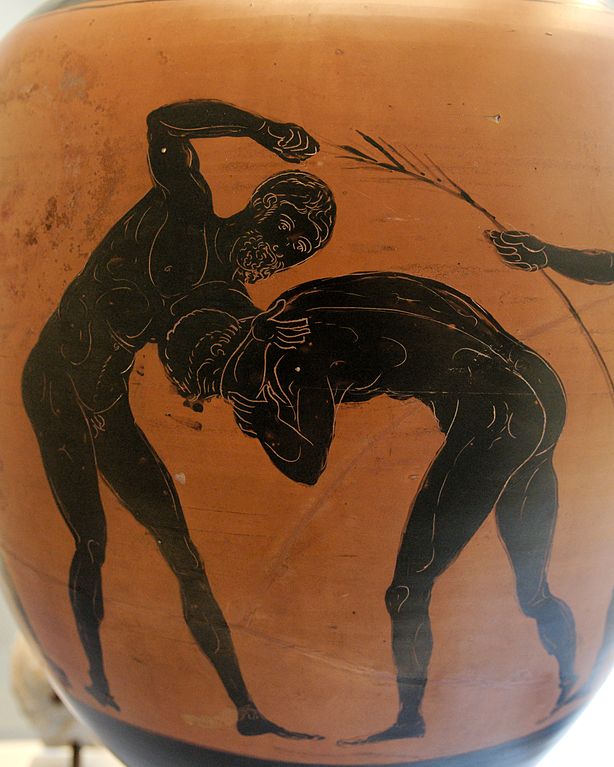

Pankration was split into multiple different phases of play, though not quite the first and second halves we see in soccer. The first phase, Ano Pankration (or Upper Pankration), required athletes to fight upright, performing kicks, punches, elbow charges, and other lethal attacks to weaken an opponent and win the battle! This was probably most similar to boxing today, or the style of Connor McGregor, aiming to keep an opponent at bay while landing as many successful shots as possible. However, ancient sources suggest that this phase often ended up in a brawl.

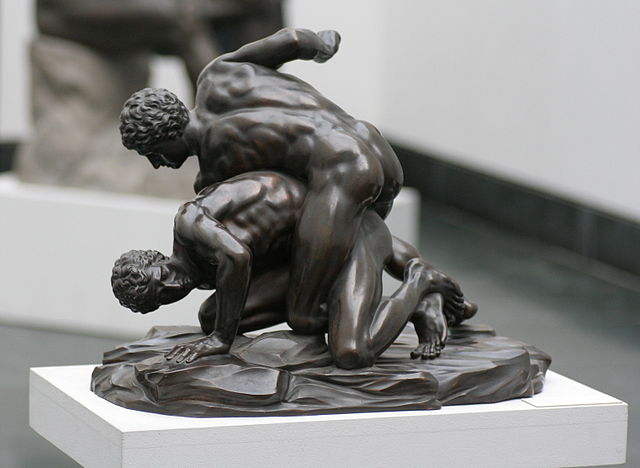

The second phase began imminently when the first opponent fell to the ground. This was called Kato Pankration, unsurprisingly translated to ‘lower pankration,’ and was much more the Greco roman wrestling that we’ve become accustomed to from painted images left behind by the respective empires. Fighters choked and wrestled one another to concede, or until unconscious. There were no time limits to the struggle, unlike in modern-day MMA, meaning combatants died, as many refused to give up after being choked—which is where the ban on gouging came to fruition.

History suggests that ancient Greeks, especially athletes at the Olympics with years of training behind them, were much more capable of tolerating pain than today in MMA. Evidence suggests that many fighters preferred to go for their opponent’s eye rather than entertain the humiliation of giving up. The signal of giving in was not the tap a certain Irishman gave to Khabib Nurmagomedov (sorry McGregor fans)—but rather a single index finger raised to signal a tap-out. Famously, Arrichion earned a posthumous victory. The fighter used the last ounce of his strength to crush and dislocate his opponents’ ankle—while being strangled on the ground, breathing his last as his opponent raised his index finger.

The strategy of a Pankrationist

Pankrationists were committed to learning as many different methods by which they could challenge and beat an opponent.

Pankrationists would aim to position themselves in the skamma, which is to say, with the low sun to their backs. Due to Greece’s outdoor nature and climate, often Pankration events would continue into the evening, during which a competitor did not want to have the disadvantage of the sun being in their face.

There was always a decision for Pankrationists as to whether remaining Ano or Kato was the best format to take. Generally speaking, staying on one’s feet was considered a more advantageous position—as falling to a knee was considered a significant disadvantage. This is most likely where the laws of boxing originated and where taking a knee became the metaphor of pundits and fans alike for conceding a big advantage to an opponent.

Fighters would often play their style defensively or offensively, reactive or proactive, to exploit an opponent’s weak side if it was known. Of course, reviewing the tapes of your opponent pre-fight was difficult for a society whose only electricity came from a God at the top of Mount Olympus—so this had to be judged at the moment. This made many pankrationists swift thinkers and good soldiers, hence its practice across the city-states, particularly in Sparta.

Common moves of a fight

A fight in Pankration would often use many different moves and techniques across its length. Punching and striking techniques featured heavily. Many derived from boxing and, in the millennia since have not changed enormously. Strikes with the legs, on the other hand, were an integral part of Pankration—as the aim was to bring the opponent to the floor in order to submit them rather than knock them out. Kicks were utilized towards the stomach, which is a prevalent theme across vases depicting Pankration—though, of course, kicks could be disastrous if countered.

Locking techniques were the bread and butter of Pankration, including arm locks, single shoulder locks, arm bars, and their combinations, and leg locks. There were not many differences to the current state of MMA in these moves, and it seems in the form of leg locks, pankrationists were the creators of the straight ankle-lock and the heel hook. There would be references made to pankrationists based on their style—whether they wrestled with the heel or the ankle.

Chokes and throws were utilized significantly by pankrationists, though throws were often ineffective in forcing an opponent to raise a finger. Chokes were the primary method by which fighters would win a contest, choking with the forearm, and aiming to restrict the trachea.

Pankration compared to Modern Mixed Martial Art

Modern-day MMA is highly different from Pankration, using many different styles, including Ju-Jitsu, Judo, and Thai Boxing. However, the main similarities relate to ground combat and its focus on submission rather than the standard knockout from boxing. In the ancient game, knockouts would occur, but far less often than ground combat, and Kato Pankration skills were tested.

Pankration was possibly the first to utilize leg and body kicks as a method by which to fatigue an opponent before going for a chokehold or submission finish. Martial artists were, of course, different and would use different combinations of hitting and grappling depending on their preference.

In the comparison, it does become apparent that MMA today has a big onus on head striking, both as a method of disorientating an opponent and finishing a fight. In ancient Olympic Games, this would often result in a fatality, by contrast to the doctors on-site and referee in the ring with participants in MMA—where fatalities are far less common.

Modern Pankration: One of the newest Mixed Martial Arts

Fortunately for all of you Pankration enthusiasts, the sport continues today. After its initial ban in 393 AD, the ancient Olympic sport found new life in the form of Neo-pankration. However, upon the revival of the Olympics in 1896, Pankration was not reinstated as a competition—its rules on hitting an opponent barehanded being of particular concern to a much more ‘polite’ society. Instead, the MMA sport divided across the decades into Boxing, Fencing, Judo, Karate, Taekwondo, and Wrestling.

Modern-day Pankration was introduced once more as a mainstream form of martial arts by Jim Arvanitis in 1969 and brought to world attention with his feature on Black Belt’s front cover. Arvanitis’ efforts were essential in getting MMA to come to the forefront of media attention, as he pioneered the return to the methods of the ancient Greeks.

Savvidis E. A. Lazaros was the founder of modern Pankration Athlima, which developed into the World Pangration Athlima Federation to help support and guide those coming into the sport for the first time. This made a lot of sense, as it meant that there was dedicated teaching of techniques from standard and a technical examination program called the endyma for the first time in the sport’s history. After the regulatory scrutiny was taken away, much like MMA, modern Pankration was accepted by FILA, known now as United World Wrestling, not the sneaker manufacturer!

These innovations gained Pankration international acclaim, resulting in its inclusion in several different games, including the World Combat Games, from 2010 onwards.