Deep within the heart of the Earth, where light has long ceased to penetrate, there exists a life form as remarkable as it is alien to our conventional understanding of life. This creature, a humble hexapod known as the deep cave springtail, holds the extraordinary title of the world’s deepest-living terrestrial organism. Found dwelling at a staggering depth of 6,496 feet (1,980 meters) below the earth’s surface, it has adapted to an environment far removed from the sunlit world we know.

The journey to this monumental discovery started in 2010, with an ambitious and diverse group of explorers known as the Ibero-Russian CaveX Team. This collaborative effort, composed of Russian and Spanish explorers, set out to explore the labyrinthine expanse of a cave system as elusive as the creature it housed.

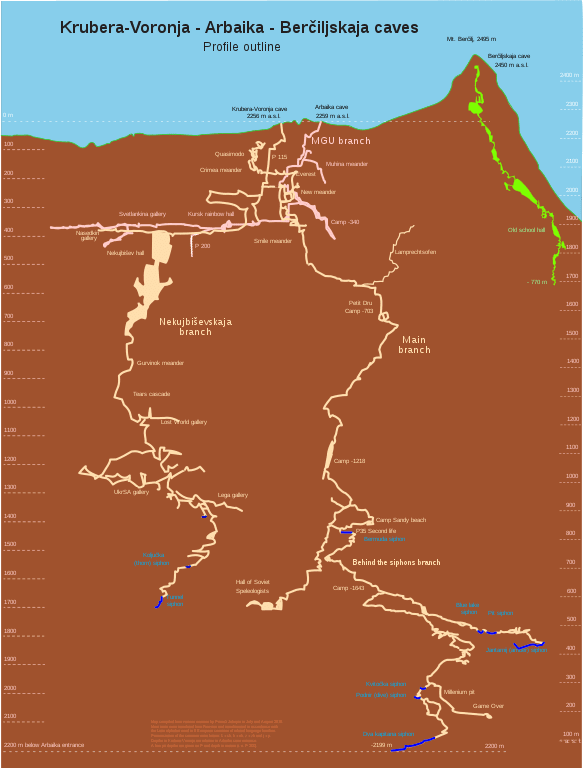

This extensive subterranean world, known as the Krubera or Voronja Cave, is a titan of natural architecture nestled close to the Black Sea in the Arabika Massif, within the expansive landscapes of the Western Caucasus mountains. Its entrance remained hidden from human eyes until as recently as 1960, a mere glimpse into its secluded existence.

This majestic cavern, however, would reveal its full grandeur only later. In 2001, the intrepid Ukrainian Speleological Association managed to traverse its dark, winding paths to a depth of 6,824 feet (2,080 meters). With this feat, the Krubera Cave was officially recognized as the first known cave to delve deeper than 6,561 feet (2,000 meters) into the earth.

Yet, it was during the Ibero-Russian CaveX Team’s exploration almost a decade later that they discovered the deep cave springtail. This eyeless, spotty creature with an affinity for cheese, was a testament to life’s extraordinary ability to adapt and thrive in the most inhospitable environments.

What is a deep cave springtail?

The 2010 expedition led by the Ibero-Russian CaveX Team presented the world with a suite of strange and previously undiscovered creatures, thriving in the depths of the enigmatic Krubera Cave. The most fascinating among them was an arthropod designated as Plutomurus ortobalaganensis. Though not quite an insect in the traditional sense, this creature embodies the unique classification of a hexapod, characterized by its articulated legs and robust external skeleton.

Members of the biospeleological team from Spain managed to lure one such specimen into a trap using a piece of cheese—an unusual bait that evidently struck the creature’s fancy. This beguiling creature, identified as a springtail, forms part of a relatively common species that can be procured quite conveniently — they’re just a few clicks away on eBay if you’re so inclined!

Springtails are far from idle purchases. They play a crucial role in stimulating composting cycles within gardens, transforming waste into fertile soil. However, their industrious nature has also earned them a less desirable reputation as pests in North America. Tiny yet tenacious, these creatures generally do not exceed 1/8th of an inch (0.31 cm) in size. They derive their moniker from their unique locomotive skill — the ability to launch themselves into the air, covering significant distances relative to their size. This feat is achieved through their furcula, a peculiar appendage on their abdomen which, when uncurled, propels them through the air in what appears to be a random, uncontrolled manner.

Springtails are hydrophilic beings, their lives intrinsically linked to water, permeating through their casings. They are naturally drawn to the moist recesses of caves, reveling in the abundant presence of fungi and decomposing plant material. These creatures are not mere inhabitants of their chosen ecosystems but critical custodians of their ecological health, upholding the delicate balance within these unique habitats.

Adapting to darkness

Plutomurus ortobalaganensis, the deep cave springtail, holds a captivating set of adaptations that have enabled its successful dwelling in cavernous abysses. The absence of sunlight in these profound depths negates the need for visual navigation, resulting in the creature being entirely sightless. However, evolution has compensated for this lack of sight by endowing it with an impressive chemoreceptor, an antenna-like organ. This chemoreceptor serves as a sensory compass, helping it traverse its dark surroundings and perhaps even leading it to the odorous lure of cheese that eventually led to its discovery. The springtail’s pigmentation, or rather its absence, further reflects its subterranean lifestyle, as it lacks any necessity for sunlight protection or camouflage from predators. Intriguingly, it exhibits a smattering of grey spots, suggesting that the creature’s descent to these extreme depths may be a relatively recent evolutionary development.

The journey that led to the revelation of this unusual creature was nothing short of a testament to human endurance and scientific ambition. The cave’s remote location presented an arduous trek laden with potential hazards, while the exploration of the cave system itself posed a grueling challenge. Over a decade of meticulous investigation was invested by the Cave X team, persevering through harsh, unyielding conditions. Their base camp, deprived of modern facilities, relied on snow as the sole source of water and imposed stringent rationing of food. The cave environment’s frigid temperatures, which ranged between a barely above-freezing 0.5 °C (32.9 °F) and 5 °C (41 °F), left the explorers persistently flirting with hypothermia as they undertook protracted specimen-seeking missions.

Prior to the unveiling of this deep-dwelling springtail, the reigning champions of Earth’s deepest living creatures were silverfish and a certain type of scorpion, discovered approximately thirty years prior, dwelling at about -3018 feet (-920 m). The unveiling of Plutomurus ortobalaganensis, thriving at almost double that depth, served as a staggering revelation to the scientific community. This discovery has not only broadened our understanding of life’s tenacity but also ushered in a paradigm shift, prompting us to rethink the breadth of biodiversity harbored in the uncharted depths of our planet.