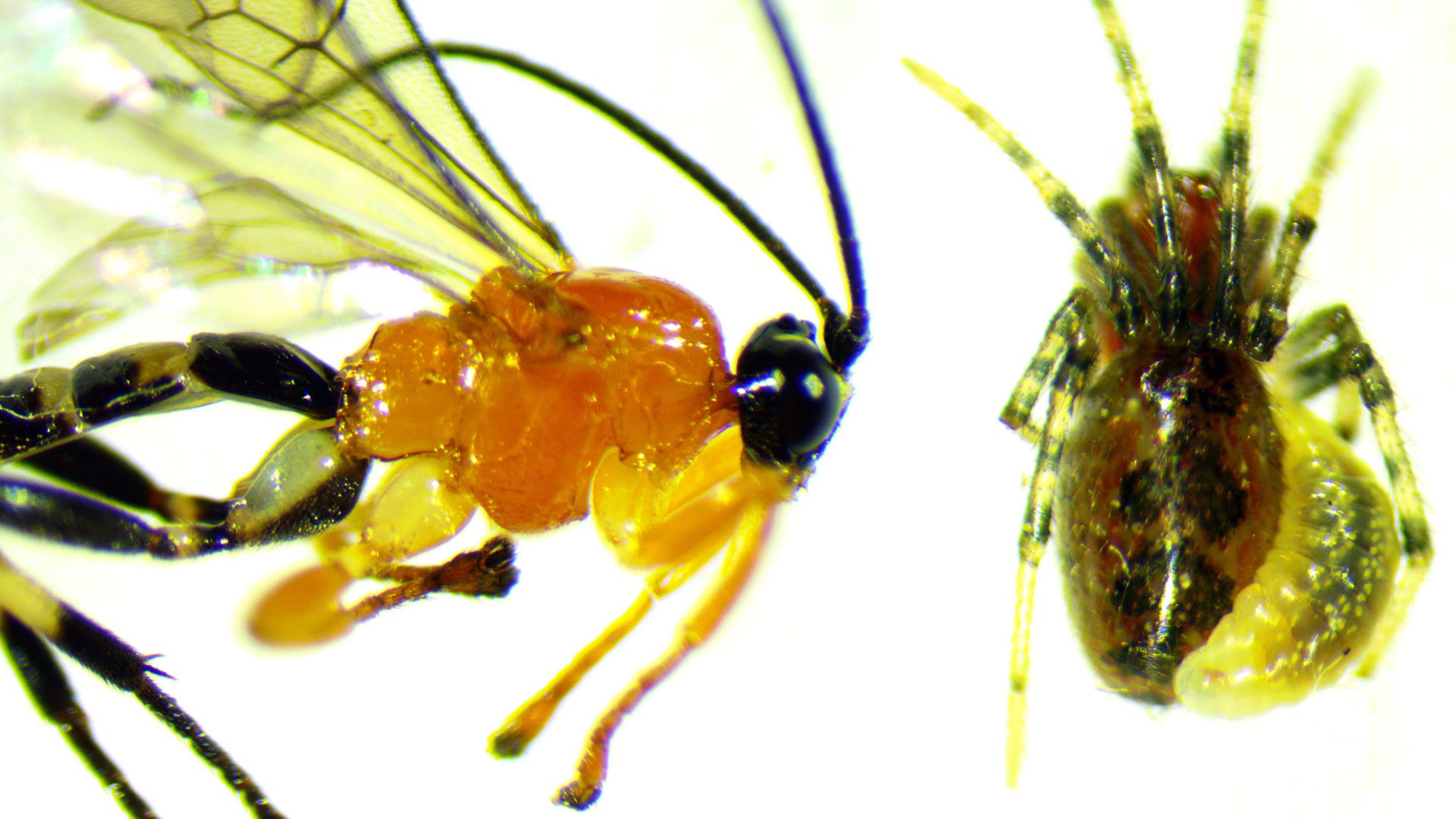

Sure, they may look like the main protagonists in a live-action adaptation of a R. L. Stein Goosebumps novel, but the parasitic wasp and the zombie spider are actually real-world creatures, and their relationship is even eerier than it sounds!

In a sentence, the Zatypota wasp—a newly-discovered wasp species—lays a larva on the abdomen of a social Anelosimus eximius spider, which transforms the spider into a zombified drudge which, in turn, abandons its colony to prepare a resting web for the larva’s cocoon!

It is a horror story for the ages, and it’s one worth telling in detail. But first, about that name.

Social spiders: arachnids who slay together, stay together

Most spiders, as you well know, are solitary creatures. Whereas many other arthropods hunt in groups, spiders hunt alone. They weave their webs alone, and then they eat their prey alone. But there are a few species of spider that don’t conform to this rule. They’re known as social spiders.

The Anelosimus eximius spiders are one such species, native to tropical America. These tiny spiders are only a few millimeters long (less than a quarter of an inch), and don’t look impressive at all on their own. But they live in large colonies of several hundred, sometimes even several thousand, spiders. Now, that’s impressive.

What’s even more impressive is the fact that they do almost everything together. They build webs together, they hunt together, they raise their brood together, and they share their prey with each other. Their way of life provides them with more food, and more protection from predators than most solitary spiders. Unfortunately, it’s also what makes them more vulnerable to parasites.

In fact, the larger the spider colony is, the higher the chances of a wicked Zatypota parasitic wasp lurking nearby. After all, who’s gonna notice a few adult wasps (or a little larva or two) in the midst of hundreds of arachnids? Well, scientists didn’t too—until just recently. And it was quite by chance as well.

“These graceful wasps—they do the most brutal thing!”

Meet Philippe Fernandez-Fournier, a PhD candidate at Simon Fraser University.

Back in 2012, he was marching through the steamy jungles of Ecuador, studying parasites in the nests of A. eximius spiders, when he noticed a few members of the group wandering off a bit, and building weird-looking webs for themselves, a foot or two away from the colony.

Out of sheer curiosity, he took a few of these webs back to his lab to study the reasons behind their odd behavior. Imagine his surprise when he realized, just a few days later, that these were no normal spider webs at all, but cocoon webs—and for adult wasps too!

“These wasps are very elegant looking and graceful,” comments Samantha Straus, a PhD student of biology at the University of British Columbia and member of Fernandez-Fournier’s research team. “But then—then they do the most brutal thing.”

In November 2018, after six years of research, Fernandez-Fournier, Strauss, and two other researchers published their findings in the Journal of Ecological Entomology. Their paper, titled “Behavioral modification of a social spider by a parasitoid wasp,” attracted a lot of attention, from both scientists and the public alike.

For a good reason: it sounded like the plot for an R-rated B horror movie. Well… a wasp one.

The ichneumonian candidate: or, How parasitoid wasps breed zombie spiders

The terrifying part of our story begins some two weeks before the appearance of the cocoon web, and a few days before the social spider wanders away from its colony. But it doesn’t begin innocently. Rather, it begins with a female wasp laying her eggs on a spider’s abdomen.

For a while, the unsuspecting host goes about its business, not knowing it’ll die soon, and knowing even less that it is about to become someone’s slave. But then the eggs hatch, and the real villain of this movie appears—the parasitic wasp larvae!

In a true Manchurian candidate fashion, a wasp larva attaches itself to a spider host, and initiates a sinister brainwashing program. Much like in Ray Bradbury’s “Fever Dream,” it slowly takes over the host’s body, whilst feeding on its hemolymph, until it is finally capable of manipulating its behavior.

“But this behavior modification is really hardcore,” remarks Strauss. “The wasp completely hijacks the spider’s behavior and brain and makes it do something it would never do, like leave its nest and spin a completely different structure.” So, we’re back where we started: the cocoon web.

Entering the web of lies, deceits—and the occasional death

It is not yet fully understood how a wasp larva induces an A. eximius spider to weave a resting web for it. But it’s very likely that—just like some other parasitic wasps—it injects its host with a specific hormone called ecdysone, which deceives the spider into believing it’s at a different life stage—namely, the final molt into adulthood.

Molting, in case you didn’t know, is the process of spiders shedding their exoskeleton, or outer layer of skin, in order to grow. During this time, they spin a resting web to lounge in it for a while until their body is fully formed.

This resting web is quite different from the normal web a social spider would use to catch its prey. But—and here’s the plot twist—it’s also pretty similar to the web that the wasp larvae need to complete their own development!

Although web types vary from species to species—or, drug to drug!—the hunting webs of most spiders feature an intricate design, whereas their molting webs are quite sparse. They are also thicker and stronger so as to support the entire weight of the growing spider.

In social spiders, normal webs are large, round, silken, and basket-shaped. Resting webs, on the other hand, are smaller, oval, and more compact, resembling a deflated rugby ball. They are the perfect web for a wasp larva to curl up in—which it, of course, does, but not before feasting on its unfortunate host. About ten days later, an adult wasp emerges.

Curtains up for the next chapter, in which—spoiler alert—pretty much the same thing happens. It’s just that the victim is different. You know, like it is in most sequels.