Evolution cranks out a seemingly endless iteration of small changes in life in the animal kingdom. You get countless species that are just a little different from some other species. And every now and then, there is a creature or plant that is just so far out of the normal that it deserves a special story.

The gympie-gympie, the deep cave springtail, the wolf cat. They are all fascinating in their own right. This story, however, isn’t about any of those. It is about the coconut crab, a creature which stands out amongst this menagerie of oddities, not just for its appearance, but for its lifestyle and diet as well!

(She’s got) the look: not your average crab

The coconut crab—or, Birgus latro if you happen to be a scientist (or a Roman, for that matter)—is an evolutionary oddball that has been around for millions of years. Also known as the robber crab or palm thief, it is the largest land-living arthropod in the world, and also one of the weirdest! For starters, all of those names are, well, descriptive! You’ll see to which extent in just a minute.

A proper behemoth this one

Although the coconut crab never quite achieves the leg span of the largest marine crab there is—which is the Japanese spider crab, measuring at 12 ft (or 4 m), claw to claw—it is still quite the heavyweight!

With an average body length of 16 inches (40 cm) and a leg span of about 3 ft (1 m), the coconut crab is not only the largest terrestrial arthropod, but also one of the largest terrestrial invertebrates known to science—if not the largest in all!

Moreover, coconut crabs can weigh up to 9 lb (or 4 kg), making them one of the heaviest land-living invertebrates as well! To put things into perspective, that’s almost as heavy as a full-grown dachshund, or a newborn baby. In terms of size, it’s twice that!

Color me attractive

Most coconut crabs are a brownish-red color, but there are striking differences between individuals, depending on their diet and habitat. In some places such as the Seychelles, for example, the majority of coconut crabs are luridly red. At Bora Bora, however—and many other islands as well—the predominant color is purplish blue.

It’s possible that, in the past, the red coloring helped coconut crabs to blend in with the coconut trees of their surroundings so as to avoid being eaten by predators. However, nowadays, all the bright colors are probably just a reproductive advantage, as the more brightly colored an individual is, the more likely it might be to find a mate.

After all, on the islands they live on, coconut crabs don’t really have any predators to worry about anymore. Their size, strength, and sharp claws make them nearly invincible to most animals. The only creatures that can really take them down are much larger animals like, well, us.

About those legs

Crabs are decapods—which means that they have 10 legs. Well, most of them do: every now and then, crabs can lose some of their legs in a fight, so it’s not strange to see a coconut crab with a leg or two missing.

Either way, out of these 10 legs, the front two are by far the most impressive. They sport two massive pincer claws, or chelae, which in mature adults have sufficient strength to crack open a coconut! They do that, coconut crabs, and they do it often! Where do you think they got their most common name from?

The next two sets of legs are specially adapted for gripping and climbing. As with other hermit crabs, they are large and powerful, which allows coconut crabs to carry their massive shells around with ease—and, of course, to climb trees. Not something you’d expect from a crab, but coconut crabs are no ordinary crabs! When god gives, they say, he gives a plenty. In the case of these fascinating creatures, that’s certainly true.

The penultimate pair of legs is a bit thinner and weaker but it has tweezer-like chelae at the end, which allow adult coconut crabs to grip and break open coconuts. The chelae are also useful for opening the hard shells of other animals, such as snails and crabs. Young coconut crabs use them to grip the inside of a coconut husk to carry for protection.

Finally, the back legs are the most primitive of all and are mostly used by female coconut crabs to tend their eggs. The males use them primarily—if not only—in mating rituals and displays.

Sneaky sniffer

Compared to other parts of their brains, the olfactory system of coconut crabs is incredibly large, comprising up to 40% of the entire brain volume and amounting to more than one million interneurons, specifically evolved to analyze olfactory input!

In this regard, coconut crabs surpass almost all other terrestrial arthropods, including honeybees and moths, suggesting that they have an exceptional sense of smell! They use it for a variety of purposes, including detecting mates and finding food. Among other things, the smells of coconuts, bananas and rotting meat are known to attract them from far away.

There’s another thing that makes this sense so special. Namely, the olfactory system in coconut crabs differentiates substantially from that of other crabs, while being incredibly similar to the olfactory system of insects!

Indeed, just like insects, coconut crabs flick their antennae to maximize the amount of odorant molecules they can sample from the environment. Moreover, just like them, they have adapted to smell things through the air, rather than by way of chemical cues in the water, as is the case with almost all other crabs.

Lifecycle: from eggs to riches

Coconut crabs mate frequently, and usually do so during the summer months. As with everything else about them, their reproductive habits are intriguing and unique too.

It all starts with a struggle

To earn his right to progeny, a male coconut crab has to first fight a female coconut crab for the prerogative to mate with her. After a while, the female gets tired, and the male gets a chance to flip her on her back.

The coconut crabs then mate. The female coconut crab lays the fertilized eggs shortly after mating, and clamps these to the underside of her abdomen, carrying them for a few months. When the time of hatching draws near, the female coconut crab scurries to the sea, and buries her eggs in the sand, where they hatch a few days later.

The floating larval phase

Like most crabs, coconut crabs spend the first few weeks of their lives in water, growing and developing. For the vast majority of these crabs, however, that is as far as they get: their ocean-going lives are usually cut short when they are eaten by predators.

The crabs only emerge from the ocean if they happen to find land in four to six weeks. The lucky few that make it to land begin their lives as miniature versions of the adults, and are soon on their way to adulthood.

The awkward teen phase

As with other hermit crabs, young coconut crabs are very vulnerable. Their shells are incredibly thin and soft, and they can’t yet protect themselves with their claws. For that reason, they must constantly search for discarded shells to inhabit. Otherwise, they are easy prey for predators.

However, finding an empty shell is not always an easy task. Coconut crabs are known to search through trash and debris in search of something that can fit them. If they can’t find anything, they resort to stealing shells from each other.

In the meantime, their soft bodies are constantly growing, and after a few months, they are ready to move on to a larger shell. Once they find a suitable one, they discard their old shell and move on to the next phase of their lives.

The adult phase

Coconut crabs reach sexual maturity between the ages of 5 and 10 years. By then, they are about the size of dinner plates. Since they grow remarkably slow, it takes them quite long to reach their full size. In fact, it is now believed that most coconut crabs will die while still growing.

There is not much data on how long coconut crabs can live, but it is believed that they can live for at least one hundred years, or even twice as that. It is not uncommon for a coconut crab to reach an age of 50 or 60. Until just a few decades ago, it was believed that this was the age they reached their maximum size.

However, recent findings have suggested that a coconut crab might take twice as much—at least 120 years!—to reach its full size. This would make it one of the longest-living land animals!

Diet: a cup of coconut water, a booby, and you

To reach a ripe old age, coconut crabs have to do two things: eat well and avoid being eaten. In most islands where they have settled, both are quite easy to do, as they are an apex predator. This means that, basically, they are at the top of the food chain wherever they are. Notorious omnivores, they will eat just about anything they can get their claws on—including other coconut crabs, and even dead humans!

Neophiliac foodies

Coconut crabs are mostly nocturnal animals and prefer to stay hidden in burrows during the day. When night falls, they come out to look for food. Because they are so big, they don’t have anything to fear from, and they can afford to be very picky eaters.

In this regard, they demonstrate a peculiar characteristic known as neophilia—meaning, a love of novelty. Indeed, when it comes to food, coconut crabs are gourmands: they quite enjoy exploring and trying on new things! Whatever seems edible to them is automatically assumed to be so.

The fact that some of these things might not belong to them or might be poisonous does not bother them in the slightest. If anything, it seems to add to the appeal. Hence, their nickname: robber crabs.

Regular robbers

It’s not unusual for a coconut crab to sneak into a campsite in order to steal a thing or two. Watches and jewelry tend to have protein odors on them from whoever’s wearing them, which makes them appealing to coconut crabs. Of course, the crabs don’t actually eat the watches and jewelry, but it seems that they do keep them as toys!

Coconut crabs also tend to pinch pots and pans and scurry away with these as well. Even though empty pots and pans have no practical value for a coconut crab, it often happens that the robber might fight with other coconut crabs to keep their newly acquired possession. For some reason, the crabs really seem to like hanging onto these pots and pans!

They also like raiding trash cans, and will often pull the entire can towards their burrow. On occasions, crabs can might climb into cottages and moored yachts in search of food.

The basic menu for the day

One of the most common foods for coconut crabs is, you guessed it, coconuts. Coconuts are very nutritious and contain a lot of water, which coconut crabs need to stay hydrated. Boasting the strongest claw grip in the animal kingdom at 1500 Newtons (337 lb force), the coconut crab is able to singlehandedly crack through the thick outer husk of coconuts to get to the sweet, milky flesh inside!

Mainly vegetarians, coconut crabs will also eat many other fleshy fruits, including figs and mangoes. They are also known to eat other animals, such as crabs, snails, and even other coconut crabs. These cannibalistic tendencies are more common in older individuals, which tend to feed on smaller, younger crabs.

Pinching boobys (and some other gruesome stories)

Even though coconut crabs are better described as scavengers rather than predators—and even though they are slow enough to be only average hunters—when they attack other animals, they are quite brutal.

In one particular example, a coconut crab was filmed killing a large seabird—the red-footed booby (Sula sula). It supposedly caught the bird asleep in its nest, grabbed its wing with its powerful claws, and then dropped it down to earth, where it ripped it apart.

The smell of blood attracted more coconut crabs, which soon devoured the entire bird, bones and all, scattering its remains around the island. Similar events have inspired what is perhaps the most fascinating theory regarding one of the most famous mysteries of the 20th century.

The disappearance of Amelia Earhart

On July 2, 1937, Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, took off from Papua New Guinea in their twin-engine Lockheed Electra on the last leg of their around-the-world flight. They were never seen or heard from again.

It is now widely hypothesized that they crash-landed on the Pacific island of Nikumaroro, only to be killed and eaten by coconut crabs. Indeed, in 1940, the island’s administrator, discovered a partial human skeleton, which he believed to be “just possibly that of Amelia Earhart.”

The bones (13 in total) were sent to Fiji for examination, but were subsequently lost, leaving the official identity of the remains unestablished. The identity of the scavenger, however, seems clear: as always, the coconut crab.

Eating coconut crabs

The reason that there were—and are—so many coconut crabs on Nikumaroro island is quite simple: the island is uninhabited. Generally speaking, people are the only real predators of these creatures, so without people around to hunt them, their population ballooned.

However, coconut crabs are rare on islands where people live, and the animals are extinct on many of the atolls that once hosted them. In fact, the coconut crab is listed by the IUCN as a vulnerable species, which means that their populations are at risk of disappearing.

Considered a delicacy, coconut crabs are hunted by people in many areas. They are also used in traditional medicine, as they are thought to have aphrodisiac effects. Sometimes, however, the crabs can accumulate poisons (possibly by consuming sea mango) and become toxic; indeed, cases of coconut crab poisoning have been reported on several occasions.

So, to sum up, a little coconut crab can purportedly act as an aphrodisiac, but a lot of it might lead to serious illness. So, one of those “get up or fall down” situations…

A place in the sun (and our cabinet of curiosities)

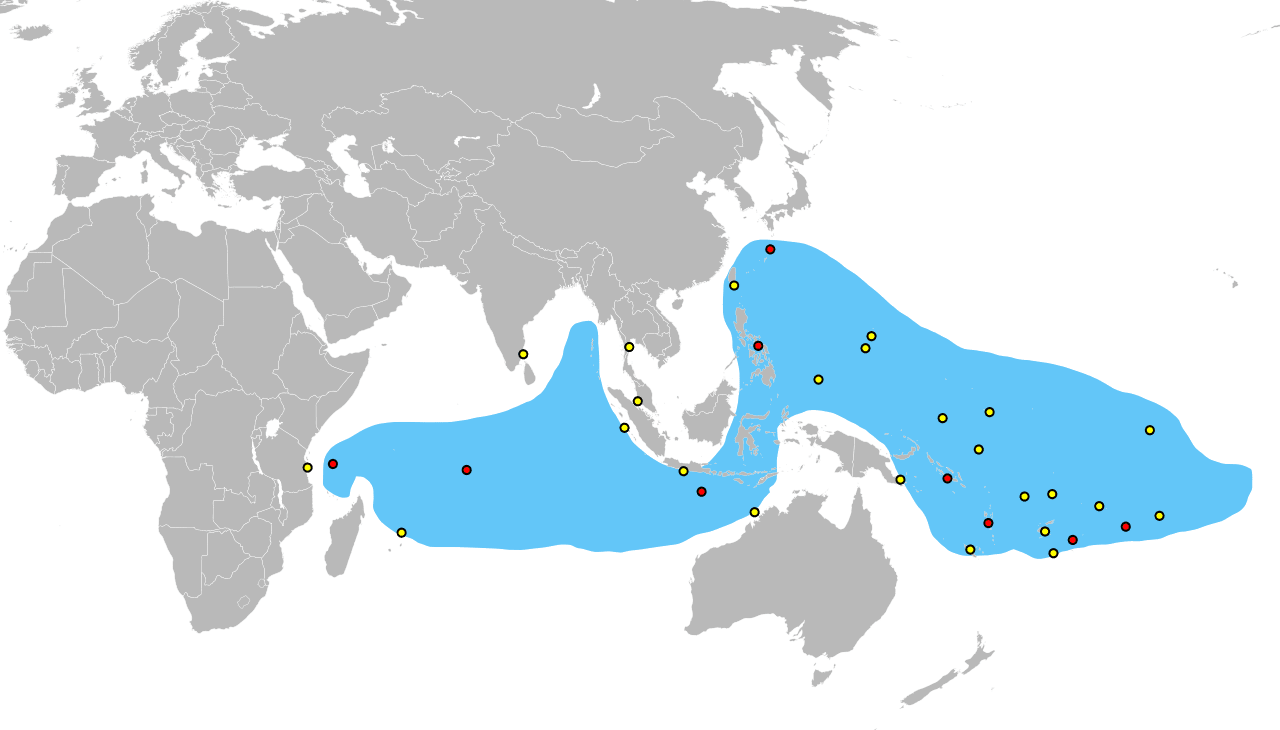

Coconut crabs are found on numerous tropical islands across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, from Zanzibar in the west to the Gambier Islands in the east, from the tropic of Cancer in the north to the tropic of Capricorn in the south.

They are particularly common on the Christmas Islands, which has the largest coconut crab population in the world. However, a significant number of crabs can also be found on the Seychelles, the Comoros, and the Chagos Archipelago, as well as near the coasts of Australia, India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines and Japan. On some of these islands, coconut crabs have been observed up to 4 miles (6 km) from the shore!

They are indeed fascinating creatures, to say the least! The largest terrestrial arthropods, they have a sense of smell that rivals that of insects, can live for over a hundred years, and are an apex predator.

They are also a delicious delicacy, a potential aphrodisiac, and a scavenger of human remains. Truly one of a kind, they are definitely deserving of their place in Odd Feed’s menagerie of natural oddities!