We often hear of the trials of child stars forced into extreme diets and grueling work schedules. But while this might seem like a modern phenomenon, it is nothing compared to what some young Italians suffered in the early modern era—the age of the castrato singers.

From the 16th to the 19th centuries, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of young Italian boys were castrated in the name of art. These men, the castrati, sang with child-like voices, and could hit high notes usually reserved for their female counterparts.

They became an extraordinary operatic phenomenon, and were in high demand for choirs. But while some had soaring careers and international success, most of these male singers had to make their way in a society that had no place for them off the stage.

In this article, we will look at who the castrati were, when and why they emerged as a cultural phenomenon, and what they sacrificed to achieve the incredible castrato voice.

What were castrato singers?

The castrati were young boys castrated before entering puberty, in order to maintain the full vocal range associated with pre-pubescent boys and girls. This meant these men could sing much higher than normal and reproduce a vocal range usually exclusive to female singers. Their child-sized vocal cords give them an incredible singing range.

But more than that, castrating young boys pre-puberty changed other aspects of their development. They would almost certainly develop a condition known as epiphyses, which stopped the bones from hardening, and resulted in their bones growing extremely long.

Consequently, they tended to have large rib cages, capable of supporting a greater lung capacity—very useful for singers, especially operatic ones. The singers were also tall and slender, a look which came across well on stage.

Castrato singers were usually high sopranos, mezzo sopranos, or contraltos.

The emergence of the castrato singers

Eunuchs were commonly found throughout the history of the world, though they were most often intended for roles other than singing. Since they were incapable of producing heirs—and thus creating dynasties of their own—castrated men were often given positions of high authority, particularly in the royal courts of the Middle East and China.

There is also some evidence to suggest that eunuchs have been prized as singers since late antiquity. Around 400 AD, for example, Byzantine Empress Aelia Eudoxia had a eunuch choir master, presumably overseeing a choir of similar men.

Church choirs and female singers

The modern phenomenon of castrato singers in the western world began in the 16th century, when the laws of the Papal States—a region of northern Italy ruled directly by the Catholic Church—created a demand for men with high-pitched voices.

Women had always had an uncomfortable place in church choirs, and were often banned from participating. One such ban was renewed by Pope Sixtus V in 1588. Without female singers, choirs had limited options for reaching higher notes. While they could use young boys, they grew up quickly and did not always have the stamina for rigorous training. Thus began the practice of castrating boys to produce male soprano singers.

Early popularity

Castrati predated the 1588 decree on female choirs. In 1589, there were already enough of them around for there to be a papal bull ordering all boys and falsettos in the Sistine Chapel Choir to be replaced by castrati. We also know that, prior to 1588, Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este sent two cantoretti (“little singers,” almost certainly castrati) to the Duke of Mantua, so that he could choose one of them for his own service.

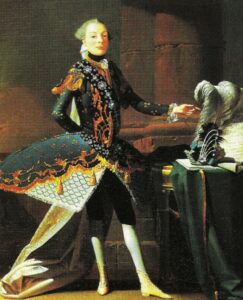

The papal endorsement of castrato singers ushered in a golden age for the phenomenon in musical history. As well as featuring in choirs around Europe, they became stars of opera. Among the most famous Italian castrati were Francesco Bernardi, also known as Senesino, and Carlo Maria Michelangelo Nicola Broschi, also known as Farinelli, who appeared in many shows in the 18th century. Probably the most famous castrato operatic role is that of Armando in Meyerbeer’s opera Il crociato in Egitto, first shown in Venice in 1824.

Popularity and influence

During the height of castrato‘s popularity in the 1720s and 1730s, around 4,000 boys were castrated each year. Some of them became extremely popular and successful, and could even transform their success into political clout. For example, Queen Elisabetta Farnese of Spain brought Farinelli to her court to improve the mood of her depressed husband, King Philip V. There, he had the ear of both monarchs. Cardinal Borghese was also known to have a favorite castrato, whom he dined with each night.

Several castrati had hordes of female fans—like the heartthrob musicians of 18th-century Europe—and were often suspected of seducing these women, despite their lack of ability to consummate the relationship in the traditional manner.

The practice of castration

While the church welcomed castrato into their choirs, they did not explicitly support the practice of castration, which remained illegal in most places. But parents would take their young boys to unscrupulous doctors willing to conduct the surgery, and then concoct elaborate stories about the “accidents” that had left their sons castrated. For example, the parents of singer Alessandro Moreschi—among the last of the castrati, in the late 19th century—claimed that he needed the operation due to an inguinal hernia.

Why would loving parents do this? The career of a castrato, if successful, could lift a large family out of poverty. Poor families with several children probably saw this as a good investment, and perhaps a gateway to a brighter future.

But the reality was quite different. Becoming a successful choir or operatic singer took more than just child-like vocal cords. Stories of Italian singing schools in the 18th century describe castrato singers engaging in hours of grueling singing exercises each day. And after all that practice, only a few castrati went on to illustrious careers. Those who didn’t “make it” often had to make a living singing on the street. With their bodies mutilated, and the public at large generally hostile to castrati, many fell into poverty and early death.

Distrust of castrato singers

Many people viewed the castrato singer with suspicion. Castrati were accused of seducing saintly women, and even turning some men towards homosexuality. They were also often considered prima donnas, notorious for throwing tantrums before their performances.

Despite audiences enjoying their performances, most people saw them as less than men, and the term castrato, plus alternative euphemisms such as “Musico” and “Evirato,” clearly had negative connotations.

The end of the castrato era

The Pope’s ban on women in church choirs made it difficult for them to sing on stage for centuries. Reflecting the church’s ideas, poet Girolamo Fenaruolo wrote in a letter: “Never is there found a woman so rare nor so chaste that if she were to sing, she would not soon become a whore.” It may surprise you that it took until 2017 for a woman, Cecilia Bartoli, to sing with the Sistine Chapel Choir.

But women were already singing in the choirs of France from the 1650s, and they became increasingly popular in Italian opera in the 18th and 19th centuries, often performing alongside castrati and out-competing them in female roles.

These changing attitudes may have contributed to the newly unified Italian state making castrato illegal in 1861. The church followed soon after, and Pope Leo XIII banned the church from using castrato in 1878. This was reinforced by Pope Pius X, in 1903, when he officially told Catholic choirs to use boys and not castrati as sopranos.

Alessandro Moreschi: The last of the castrato singers

The last castrato to perform in the Sistine Chapel Choir was Alessandro Moreschi, who had joined the choir at age 15, in 1873. He stands out among the castrato singers because he made a series of recordings between 1902 and 1904. While many people say that he was well past his prime when he made these recordings, they still offer a rare insight into this musical phenomenon and why the practice continued for so long. You can hear his rendition of Ave Maria here.

Looking back

Castrato receded into obscurity with the coming of the modern age. Eunuch singers are now a thing of the past, though some men can suffer similar symptoms due to conditions such as Klinefelter syndrome or Kallman syndrome, which interfere with normal puberty. Today, male singers must generally rely on a falsetto voice to hit high notes. There are no singers like Farinelli or Alessandro Moreschi. It seems clear, though, that the price paid by castrati—grueling musical training, social ostracism, and above all, permanent bodily mutilation—was entirely too high.