Dare to imagine, for a moment, that you’re traversing the cobblestone streets of Victorian-era London at nightfall, the solitary echo of your footsteps a stark reminder of your loneliness. The inky darkness seems to press against your very skin, and the distant hooting of an owl is the only indication that you aren’t utterly alone. Suddenly, the prickling sensation of unseen eyes bears down on you, causing every hair on the back of your neck to stand on end. Is this merely the conjuring of an overactive imagination, or something more? For the residents of 19th-century London, such a feeling was no stranger; rather, it was an all too familiar dread. A fear-inducing specter, known by the moniker of “Spring-heeled Jack,” was said to lurk in the gloom, ready to strike terror into the hearts of unsuspecting citizens.

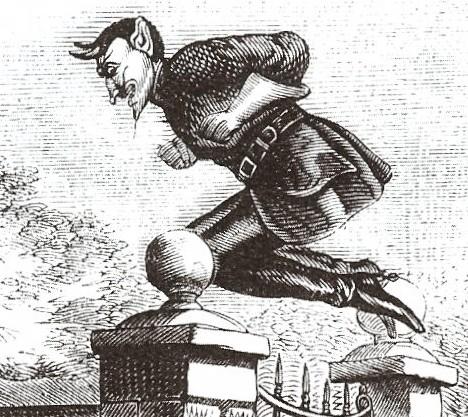

The folkloric figure, affectionately or perhaps fearfully named “Spring-heeled Jack” for his reputed uncanny ability to leap extraordinary distances and heights, emerged in the folklore of Victorian London in the early 1800s. The tales of his mischief were as numerous as they were terrifying, his escapades ranging from mere jester-like pranks to inducing swooning fits and fainting spells among his victims. His unmatched agility enabled him to swiftly retreat from the scenes of his pranks, leaving only the echo of frightened whispers in his wake.

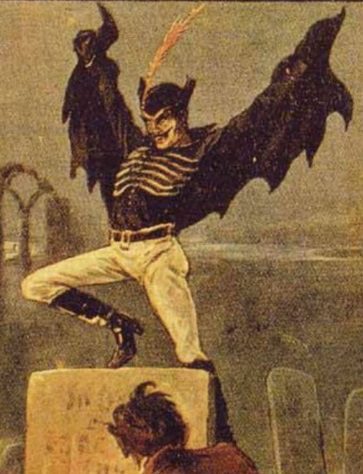

Those unlucky enough to cross paths with him shared strikingly similar descriptions of his terrifying visage. Witnesses spoke of clawed hands, like the talons of a predatory beast, that could send chills down the bravest of spines. His eyes were described as eerie “balls of red fire,” burning with an intensity that could be seen reflecting in the widened eyes of his prey. The demon-like apparition was said to be garbed in a haunting ensemble: a long, billowing black coat that whispered of endless darkness, a mysterious helmet, and an oilskin suit that clung tightly to his form, glinting ominously under the scarce light of the moon. This spectral image seared itself into the collective consciousness of the era, manifesting in a myriad of chilling illustrations that amplified the citywide fear of this nocturnal terror.

Ghostly origins

One might be intrigued to learn that the iconic image we now associate with Spring-heeled Jack was not his original form. Indeed, the origins of this diabolical character are grounded in somewhat more terrestrial imagery. The figure that would eventually transform into the dreaded phantom of London’s streets first appeared as an eerie spectral bull, sighted in South East London in the year 1837. As whispers of this so-called “Suburban Ghost” fluttered across the cityscape, the creature’s form, as if imbued with a life of its own, began to morph into an assortment of beasts and mythical entities, each more fantastical and petrifying than the last.

Caught within this whirlwind of rumor and intrigue, the burgeoning press of the era seized upon this opportunity. Through purported first-hand accounts of terrified witnesses, they bestowed upon this spectral menace the moniker “Spring-heeled Jack.” This naming not only distinguished him from the plethora of ghost stories pervading the era but also marked his transformation into an enduring and unforgettable figure in the annals of urban folklore.

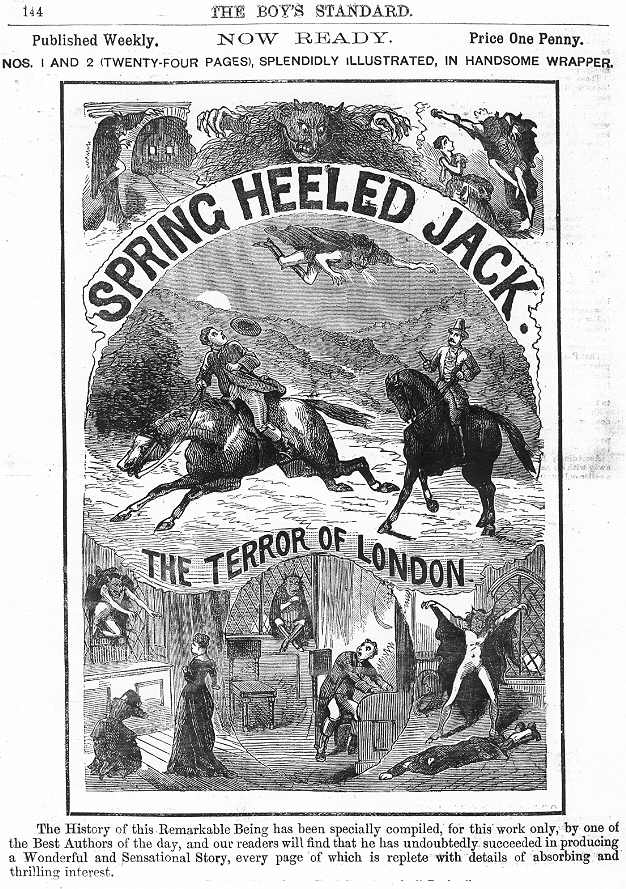

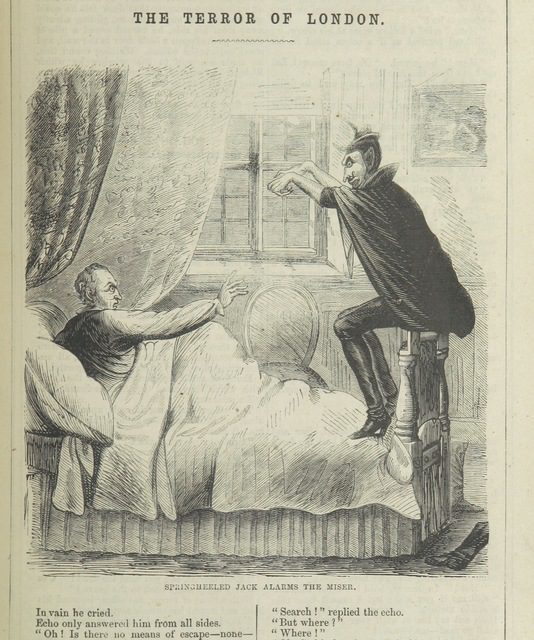

His name and image found their way into the very heart of Victorian popular culture, feeding the imagination of the masses. He became the brooding anti-hero of the “penny dreadful” literature of the time, his terrifying escapades thrilling the readers. In households, his name was invoked as an instrument of discipline, with parents warning mischievous children of his arrival—similar to the “bogeyman” of modern-day lore. Thus, Spring-heeled Jack navigated the delicate boundary between urban legend and real-life criminal, his existence endorsed by alleged eyewitnesses and his legacy amplified by an enthralled public.

This dual status as both a tangible threat and an intangible legend played a pivotal role in his enduring infamy, ensuring that the specter of Spring-heeled Jack, with his fiery eyes and remarkable agility, continued to haunt the collective imagination of Victorian London and beyond.

A Victorian villain

Indeed, the macabre myth of Spring-heeled Jack was grounded in terrifying reality, with accounts of actual victims, often solitary and defenseless women, lending an eerie credibility to his tale. The first account of his horrifying exploits emerged in 1837, painting a vivid picture of the chaos he induced. The victim was a young servant girl, Mary Stevens, who, while making her usual trek through Clapham Common on her way to work, found herself the sudden target of this ghastly figure. As she later described, the figure abruptly leaped out at her, ensnaring her with an iron grip. He then attempted to steal a kiss while simultaneously tearing at her garments with what she later recounted as claws “cold and clammy as those of a corpse.”

The spectral assailant did not allow much time to pass before selecting his next victim. The very next day, reports emerged of a phantom figure audaciously springing in front of a passing coach, which resulted in the coachman losing control and crashing the vehicle. Onlookers to the scene were left astounded as the culprit evaded capture by taking an extraordinary leap over a 9-foot (2.7 m) wall. As if this feat were not startling enough, he was said to have done so while emitting a spine-chilling, high-pitched, and almost hysterical cackle that echoed through the London night.

News of these bizarre and brazen attacks spread like wildfire, and before long, the press latched onto these sensational stories. The tales of Spring-heeled Jack’s exploits, printed in black and white, soon began to circulate in the city’s papers, saturating local conversation and fanning the flames of fear. Thus, Spring-heeled Jack was catapulted into the public consciousness, transforming from mere rumor into a notorious and fearful figure whose dark shadow loomed ominously over the cityscape of Victorian London.

The Alsop and Scales case

One of the most widely circulated and deeply chilling incidents involving Spring-heeled Jack involved the traumatic experiences of Jane Alsop and Lucy Scales, two unsuspecting teenage girls who found themselves the prey of the leaping menace in the frigid month of February 1838. These particular cases, marked by a sinister masquerade and the dread of blue and white flames, resonated deeply in the public consciousness and stoked the already raging fire of fear in the hearts of London’s populace.

Alsop’s ordeal began on an ordinary evening when a man knocked on her door, claiming to be a police officer with urgent news: they had cornered the elusive Spring-heeled Jack in a narrow alley near her home. However, as she rushed to accompany him to the scene, the dim glow of the gas lamps revealed a strange, anomalous detail—the man was swathed in a flowing black cape, hardly the uniform of the police force. By the time this discrepancy was registered, it was tragically too late. The man turned to face her, and to her sheer horror, he disgorged a torrent of blue and white flames from his mouth and eyes before launching himself at her in an attempted assault.

A disturbingly similar scenario befell Lucy Scales just nine days later, casting a new wave of fear over the city. Returning home from a visit to her brother in the affluent borough of Limehouse, Scales was startled by the sudden appearance of a man. His attire bore a striking resemblance to the deceitful ‘policeman’ in Alsop’s tale. The similarities didn’t end there—the man proceeded to release a burst of brightly colored flames from his face. The encounter sent Scales into a state of intense distress; she later reported that the shocking spectacle had caused temporary blindness and sent her into uncontrollable fits.

These harrowing episodes painted a terrifyingly vivid picture of Spring-heeled Jack’s antics and escalated his reputation from an urban myth to a tangible and deeply dreaded specter of the London streets.

A public nuisance

Just as in the modern era, where we firmly reject the idea of a repeat offender – especially one armed with claws and capable of vomiting flames – freely roaming the streets, the sightings of Spring-heeled Jack provoked a wave of anxiety among the Victorian populace. Even before the horrific episodes involving Scales and Alsop, Jack had infiltrated societal consciousness and popular media to such an extent that he was the focal point of a notable public gathering in 1838. On the chilly morning of January 9, London’s then Lord Mayor, Sir John Cowan (1774–1842), took to the podium to address an unsettling issue.

At the heart of his speech was an anonymous grievance penned by a resident of Peckham. This written account detailed the traumatic experience of a servant girl from a well-to-do family, who had been so profoundly terrified by an encounter with a mysterious entity that she was yet to fully regain her composure.

The Mayor’s recounting of this harrowing incident sent ripples through the audience, and the ripple soon became a tide. Several individuals stepped forward to recount eerily similar tales involving other servant girls in the areas of Kensington and Hammersmith. The pattern of reports suggested a targeted terror campaign that seemed too coordinated to be random incidents.

Unsurprisingly, this story—ripe with fear, mystery, and the sensational—made for ideal fodder for the press. The Times, a prominent news outlet of the day, seized upon the narrative, stirring public curiosity and fear in equal measure. Just as the public meeting had commanded attention, so too did the publication. Letters flooded in from readers who claimed to have seen or knew someone who had encountered the infamous Victorian menace.

The identity and motives of the malevolent figure haunting London’s cobblestoned streets remained shrouded in mystery, but one thing was clear: someone, or something, was sowing terror with purposeful intent. The question remained: Who was this phantom, and why did they inflict such horror? The city held its breath, awaiting answers in the eerie shadows cast by gas lamps and the flickering pages of penny dreadfuls.

So just who was the man beneath the cape?

Over the passage of time, a variety of theories have surfaced concerning the true identity of Spring-heeled Jack. These hypotheses span a wide spectrum, extending from the realms of scientific skepticism to considerations of group psychology and even explorations into the supernatural. A faction of researchers are inclined to explain the phenomenon as a case of mass hysteria, a well-documented sociogenic illness that compels large collectives to manifest similar physiological or psychological symptoms, often without an evident physical cause. This phenomenon also referred to as “conversion disorder,” serves to incite communal belief in unusual or extraordinary occurrences.

A contrasting, more cynical viewpoint suggests that the figure of Spring-heeled Jack may, in fact, be the manifestation of one or multiple individuals who either opportunistically or premeditatedly engaged in parallel types of offenses.

One person of interest that has been singled out by historical scrutiny is the notorious Marquess of Waterford, an Irish nobleman who lived from 1811 to 1859. This individual was infamous for his overtly misogynistic tendencies, and his reputation with law enforcement was less than stellar, largely due to his frequent indulgence in alcohol-fuelled misconduct. Consequently, his name was not an uncommon sight in the newspapers of the day, which were only too eager to chronicle his drunken escapades that ranged from vandalizing property to assaulting police officers.

His scandalous behavior, along with his delight in “springing on travelers unawares,” a remarkably reminiscent trait of Spring-heeled Jack, earned him the colloquial moniker of “the Mad Marquis.” His infamy and antics aligned suspiciously well with the harrowing deeds attributed to the terrorizing phantom that was Spring-heeled Jack, raising eyebrows and fueling speculation about whether the two notorious figures might, in fact, be one and the same.

The role of the press

To fully comprehend the phenomenon of Spring-heeled Jack, it is critical to view it through the lens of its historical context. The era in question was marked by the sweeping currents of the Industrial Revolution, which heralded significant advancements in printing technology. Coupled with an unprecedented rise in public education leading to declining illiteracy rates, the number of readers in society multiplied considerably. This, in turn, stimulated greater demand for reading materials, including books, periodicals, and critically, newspapers which thrived on sensationalist narratives.

Victorian Britain, in particular, was grappling with alarmingly high crime rates, a scenario that proved to be fertile ground for such newspapers to flourish. By packaging and presenting sensationalized stories, they capitalized on the prevailing public sentiment, turning fear into profit. Their readers, in turn, were often all too willing to accept these alarming accounts at face value.

The impact of the press cannot be underestimated when considering how the tale of Spring-heeled Jack came into the limelight. Other mediums of news dissemination, such as the popular “penny dreadful” literature of the time, also played a pivotal role. These inexpensive, sensational works of fiction were widely consumed, furthering the reach of such stories.

This sociocultural backdrop provided the ideal ecosystem for the propagation of the Spring-heeled Jack narrative, allowing it to take root and spread throughout Victorian society. Given these factors, it is hardly surprising that the urban legend of Spring-heeled Jack was not merely regarded as a fanciful tale, but was genuinely believed, enabling it to gain such a stronghold in the societal consciousness of the time.

The legend lives on

Probing into the enigma of Spring-heeled Jack and his spectral presence in 19th-century Britain provides a captivating window into the era’s rich tapestry of folklore and societal attitudes toward crime. The legacy of Spring-heeled Jack offers a deeper understanding of how fear, real or imagined, can capture the public imagination and propagate cultural phenomena that span generations.

The tale of Spring-heeled Jack serves as a potent illustration of the influential role of the press in shaping public opinion and perpetuating legends. The press was not just a passive recorder of events, but an active participant in their creation and narration. They wielded considerable power in amplifying the narrative of Spring-heeled Jack, weaving together alleged sightings and reports into an interconnected tapestry of fear and fascination.

The enduring mystery surrounding the true nature of Spring-heeled Jack—whether a product of mass hysteria, an imaginative piece of folklore, or a sinister entity with malicious intent – continues to captivate our collective consciousness. Regardless of his actual existence or lack thereof, he stands as a stark embodiment of society’s deepest fears and anxieties, a phantom from the past that still echoes in our imaginations.

As we walk our solitary paths home in the twilight hours, the legend of Spring-heeled Jack serves as a chilling reminder of the power of myth and the shadows that our minds can cast. Despite our advances in understanding the world around us, there still exists a primal part of us that dreads the flicker of an unknown figure in the corner of our eyes, the unwelcome companion in the desolate alleyways of our nightly journey home. Whether real or imagined, Spring-heeled Jack continues to haunt us, a reminder of our fears and the enduring power of legends.