It was only in 2005 that the United States Supreme Court banned the execution of minors—those under 18—considering it a cruel and unusual punishment. The practice had faded from use in the decades prior, with several states issuing individual bans and many banning the death penalty entirely from 1846 onward; 27 states still have the death penalty.

But between 1642 and 1924, there are records of 102 juveniles being executed in the United States. The number is probably much higher, due to many people not knowing exactly how old they were at the time of their death. Young people of color, both Native Americans and African Americans, are over-represented among those executed.

The youngest girl ever to be executed in the United States was Hannah Ocuish, a half-Native American girl who was hung for the murder of Eunice Bolles in Connecticut in 1786. Today, the NAACP and the Innocence Project are investigating whether her execution was itself a crime born of racism and the need to find someone culpable for the death of Eunice, a young daughter of an influential local farmer.

The murder of Eunice Bolles

Eunice Bolles was the six-year-old daughter of a local New London County farmer in Connecticut. She disappeared on her way to school on 21 July 1786. Her body was later found next to a stonewall on a public road connecting New London with Norwich. She looked as though she had been battered by falling debris from the wall; rocks were lying around her head and torso, but because of her injuries, no one thought it was an accident.

A group of local men started investigating, and one of the witnesses they encountered was Hannah Ocuish. The girl worked as a servant for a widow who lived about three miles outside New London.

While she claimed not to know anything specific about what happened, she said that she had seen a group of four boys in the area earlier that day. The men tried to locate these four boys, but they were never found. Wondering why she had invented this information, their suspicion fell on Hannah.

The confession of Hannah Ocuish

The following day, the men returned to speak to Hannah Ocuish and questioned her. She continued to deny knowing anything about what happened to the younger girl.

Unsatisfied, they dragged Hannah to the Bolles’s house and forced her to look at Eunice’s body. At this time, the men claimed that she broke down and confessed to the crime.

According to their account of the confession, Hannah admitted to having a grudge against Eunice following an encounter five weeks earlier. Hannah explained that Eunice had caught Hannah stealing strawberries during the strawberry harvest. Eunice had threatened to report her, and Hannah vowed revenge.

According to their account of Hannah’s confession, when Hannah had seen Eunice walking to school the previous day, she lured her off the road with a piece of calico. Once she and Eunice were alone, Hannah had beaten her nearly to death with a rock and then strangled her. She then placed rocks around the body to make it look like a wall had fallen in a horrible accident and fled the scene.

Hannah was arrested on the basis of this confession. No other evidence was collected against her, but there were also no other reported suspects.

The trial of Hannah Ocuish

When Hannah was taken to trial, she pled not guilty, seemingly reneging on her earlier confession. That Hannah did not stand by her confession is also suggested by a sermon delivered by the local minister Henry Channing, who had visited Hannah several times in prison while she was awaiting execution.

According to a sermon by Henry Channing on the occasion of Hannah Ocuish’s execution, she had not repented. He said she would be punished in the afterlife, “unless you now obtain a pardon, by confessing and sincerely repenting of your sins.”

Witnesses report that Hannah Ocuish was calm and unfazed at her trial, almost as if she did not understand the seriousness of the charges against her. This has been used as evidence that she may have suffered from a mental disability.

Later, as she was awaiting execution, she was distressed. On the day of her execution, December 20, 1786, she thanked the Sheriff for his kind treatment over the previous months before stepping out to her fate. But onlookers noted that she was distressed, greatly afraid, and looked like she was waiting for someone to help her. This paints a picture of a girl much more cognizant of her situation than described at the trial.

Was Hannah Ocuish a violent criminal?

The stories that circulated surrounding Hannah’s trial suggested that she was a violent criminal with a malicious nature. Following the death of Eunice Bolles, local children claimed that they had always been afraid of Hannah. But it is hard to know whether this was true, or simply prejudice harbored by the local community who wanted to believe she was guilty.

Hannah’s life had certainly not been an easy one. She was half-Pequot Native American through her mother; her father was not reported and was presumably unknown. Hannah’s mother was reportedly an alcoholic, and there was a strong implication that she worked as a prostitute.

Hannah lived with her mother in Groton until the age of 6. At this age, Hannah and a brother of hers that was two years older were accused of mugging and almost killing a younger girl. Hannah and her brother reportedly beat the girl to within an inch of her life and stripped her of her clothing and gold jewelry. While the pair argued over the spoils, the girl awakened, ran away, and reported the crime.

Local officials decided to remove the children from their mother, which meant passing them into bound servitude. Nothing more was heard of Hannah’s brother, but she ended up working as a servant for a widow a few miles outside of New London.

Henry Channing’s sermon on Hannah Ocuish

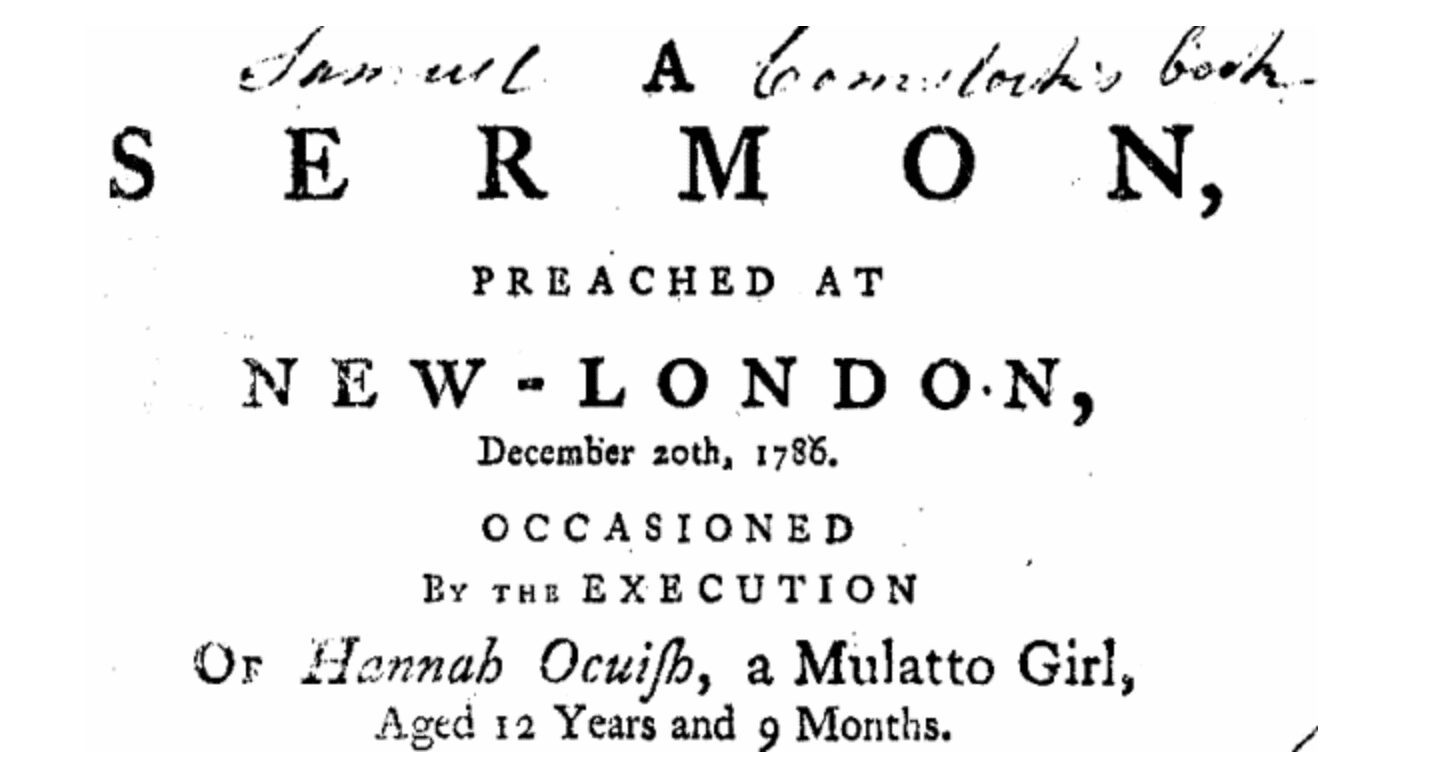

Hannah’s character was probably attacked during the trial, and certainly by the local Minister Henry Channing, who published his sermon: God Admonishing His People of Their Duty, as Parents and Masters: A Sermon, Preached at New-London, December 20th, 1786. Occasioned by the Execution of Hannah Ocuish, a Mulatto Girl, Aged 12 Years and 9 Months. For the Murder of Eunice Bolles, Aged 6 Years and 6 Months.

Channing used his sermon to lecture the community on the dangers of not raising their children correctly, suggesting that Hannah’s criminal behavior was the “natural consequence of too great parental indulgence” and proclaimed that “appetites and passions unrestrained in childhood became furious in youth and ensure dishonor, disease, and untimely death.”

This seems a strange invective to throw at a poor girl who was unlikely to have been indulged as a child, considering she had worked as a bound servant since the age of six. The widow does not seem to have had occasion to complain about Hannah in the six years she was with her.

Did Hannah Ocuish kill Eunice Bolles?

It is unlikely that the Innocence Project will be able to determine whether Hannah actually committed the crime for which she was executed with such limited evidence to interrogate.

Hannah’s confession certainly seems suspicious, not only because she denied the crime when she was first questioned and later at trial. The motive for the crime was apparently provided by Hannah herself and seems weak. While Eunice may have threatened to tell on Hannah for stealing fruit, this never happened, as the girl faced no consequences for those actions. It seems possible that Hannah admitted that she knew the little girl because of this interaction, and was then told that this was her motive for the accused actions.

The idea that she could have lured Eunice to a private corner with a piece of calico fabric also seems strange. Based on their previous interaction, Eunice would likely have been suspicious of Hannah and avoided being alone with her.

On top of this, there is no indication that Eunice was robbed. Given that robbery was the primary motive of the other attack in which Hannah had been previously implicated, surely a poor girl like herself would have taken any objects of value even if the theft had not been her primary motive for the murder.

What’s next for Hannah’s investigation?

If the Innocence Project has shown anything through its years of work, it is that false confessions are more common than many people believe and relatively easy to extract from young, vulnerable, scared individuals. Institutional racism may have led the community to truly believe that this heinous crime was committed by a “mixed race” girl with a questionable past.

Modern investigations started in March 2020 and will probably focus on whether Hannah should have been executed. Certainly, by today’s standards, she would have been deemed too young, and if she did indeed have a mental disability, this would have been a mitigating factor as well.

But, at the time, the Murder Act of 1752 meant that committing murder required a mandatory death sentence by hanging. Age was not viewed as a mitigating factor, and the onus was on the defense to prove that the child did not know what they were doing was wrong; otherwise, it was assumed that they understood.

Hannah Ocuish is considered the youngest person executed in the United States, and we likely will never know if she really committed the crime.