As Americans, we are well-acquainted with the tales and traditions of Thanksgiving and the explosive celebrations of Independence Day. Yet, there’s another significant date that is lesser-known but of profound importance to our nation’s story: Juneteenth.

Coined from the amalgamation of “June” and “nineteenth,” Juneteenth stands as a remarkable milestone that signals the end of a dark chapter in American history – the institution of slavery.

The backdrop of this significant date is the American Civil War, a tumultuous period of national divide that endured from 1861 to 1865. This era of conflict, characterized by bloody battles and societal strife, concluded with the triumph of the Union over the Confederacy. The Union, composed of the industrially-progressive northern states, was a staunch opposer of slave labor. In contrast, the Confederate states, the defeated faction, were an assembly of southern territories that heavily relied on the enforced labor of enslaved people for the cultivation of commercial cash crops, such as cotton.

The leader of the victorious Union, President Abraham Lincoln, had already set the stage for a monumental shift in the nation’s fabric by promulgating the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, having initially issued it in September the previous year. This landmark edict decreed that enslaved people within the Confederate states were to be “then, thenceforward, and forever free.” This decree symbolized a significant pivot in America’s societal structure and moral compass, marking the dawn of a new era of liberty.

However, as with any societal transformation, change was not immediate. It would take another two and a half arduous years for the message of the Emancipation Proclamation to echo across every state, reaching the ears of every enslaved individual. Thus, Juneteenth signifies the realization of a freedom that had been proclaimed but not yet actualized, marking an essential turning point in the journey towards a more equitable America.

Texas and Juneteenth

Despite its involvement in the American Civil War, Texas managed to remain isolated from the reach of the Emancipation Proclamation for an array of reasons. This largely rural and remote state—furthest west of the Confederate stronghold—encountered minimal conflict, which was conducive to its relative isolation. A dearth of Union military presence in Texas as a consequence of the limited combat further contributed to its detachment from the cascading national changes. This unique set of circumstances led to Texas being the final state to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation, a reality that materialized on June 19, 1865.

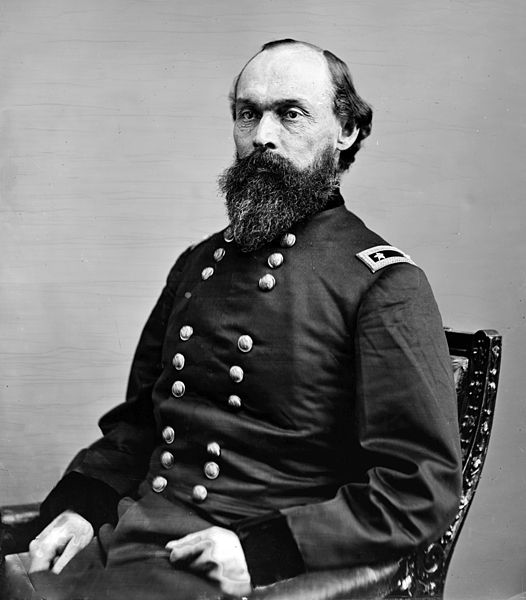

This seminal date—two months subsequent to General Robert E. Lee’s admission of the Confederacy’s defeat—ushered in US Major General Gordon Granger and a formidable contingent of 1,800 Union troops to Texas. Their purpose was unequivocal: to promulgate General Order, Number 3, a message imbued with the power to alter the destiny of thousands. The words reverberated through the air: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

The repercussions of this order rippled across Texas, reaching even the most remote corners of the state. The newly liberated population, previously subjected to the cruel yoke of slavery, burst into celebrations of joy and relief. This historic day of jubilation and liberation, marked by boundless enthusiasm, has since been christened “Juneteenth”—a portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth”—and represents a cornerstone of African American history and culture.

True freedom at last?

It’s crucial to highlight that the Emancipation Proclamation did not extend to slaves in former Confederate states that had been claimed by the Union during the Civil War, nor did it include slaves residing in the so-called border states. The shackles of their bondage were officially shattered six months post-Juneteenth, on December 18, 1865. This historic moment was marked by the enactment of the Thirteenth Amendment, which resoundingly declared the nationwide abolition of slavery within the United States.

In an ideal world, the Emancipation Proclamation would have instantaneously liberated all 250,000 slaves residing in Texas, as well as those enduring servitude in other Confederate territories. The social fabric was supposed to transform overnight; slaves would metamorphose into paid laborers, while their former masters would transition into employers. This new social order was encapsulated in General Order, Number 3, which asserted, “The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages.”

Nevertheless, the reality proved starkly different. Freedom did not touch every enslaved person instantaneously, or even uniformly. A substantial number of slaves had originally been enslaved in states beyond Texas. However, as Union forces advanced during the Civil War, their slave owners forcefully moved them to Texas, perceived as a sanctuary from Union influence. Astoundingly, it was incumbent upon the slave owners to inform their slaves about their newly acquired freedom following General Granger’s proclamation of the Emancipation Proclamation—a revelation that many strategically delayed until after the harvest season to exploit their labor and enhance profits. Shockingly, aided by politically influential figures such as the ex-Confederate Mayor of Galveston, some freed individuals were coerced back into labor.

Additionally, the conclusion of the American Civil War marked the advent of the notorious Jim Crow laws in the South. These laws insidiously enforced racial segregation, leading to the systematic separation and differential treatment of African-Americans and white Americans. Thus, despite the formal abolition of slavery, the personal freedoms of African-Americans continued to be stringently curtailed for many ensuing years, a fact that underscores the enduring struggle for racial equality.

Celebrations: 1865 to today

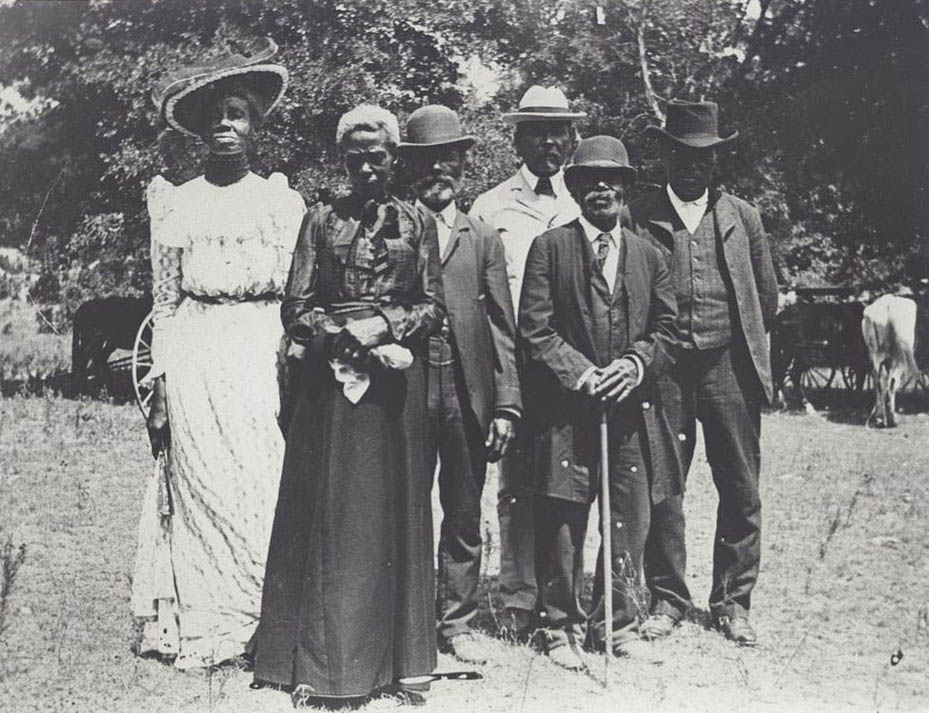

The triumphant declaration of the Emancipation Proclamation sparked widespread jubilation among newly emancipated African American men and women. In an expression of their shared joy and newfound freedom, the first organized Juneteenth celebration was initiated the following year on June 19, 1866, though alternate commemoration dates of January 1 and 4 were also observed by some communities.

The insidious realities of racial segregation, however, barred African Americans from participating in public Juneteenth festivities. To counteract these restrictions, cohesive communities across various cities joined forces, amassing their resources to purchase sizable plots of land. One notable example was an $800 parcel acquired in Houston, Texas, in 1872, which has since been immortalized as Emancipation Park. This culturally and historically significant expanse of land held the distinction of being the sole park accessible to African Americans throughout the Jim Crow era.

The intricate tapestry of Juneteenth festivities was woven with threads of political activism, with rallies aimed at equipping and inspiring the newly liberated African Americans to exercise their voting rights. The celebrations also encompassed religious sermons and recitations of the Emancipation Proclamation, accentuated by an abundance of food and recreational games. Participants, donning their finest attire, reveled in the festivities with exuberance and pride. Some former slaves even embarked on a pilgrimage to Galveston, Texas, the hallowed site where General Granger had first delivered the transformative Emancipation Proclamation in 1865. Over the decades, the fabric of these celebrations has been maintained, enriched by additional traditions such as family picnics, contests, and cookouts featuring red-hued foods and beverages, emblematic of enduring resilience.

However, throughout history, the continuity of Juneteenth celebrations was frequently jeopardized. The repressive Jim Crow laws, economic downturns, global crises like World War II, and, surprisingly, even the civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s, posed considerable challenges. Yet, Juneteenth persisted, finding renewed life and wider recognition in the wake of the Great Migration. This term was coined to describe the monumental exodus of African Americans from the southern states toward the northern territories between 1916 and 1970. This demographic shift effectively disseminated the observance of Juneteenth across the entire nation, solidifying its place in American history and culture.

Texas: Last to enforce, first to adopt

Ironically, although Texas was the last Confederate bastion to have the Emancipation Proclamation enforced, it emerged as the first state to officially recognize Juneteenth as a significant commemoration in 1979. This recognition was quite fitting, given that Texas was the birthplace of these festivities and remained the state most synonymous with them. Since then, almost all US states have emulated Texas, with only four exceptions, amplifying the calls for Juneteenth to be recognized as a national holiday, a proposition that has even reached the hallowed halls of the US Congress.

Juneteenth might not hold the same ubiquitous recognition as other American holidays, but it represents a turning point in the country’s history that deserves broader acknowledgment. The significance of this day is not confined to history textbooks; it resonates with our present narrative and has the power to shape our understanding of the future. Juneteenth serves as a poignant reminder of the journey toward freedom and equality – a journey that is still underway.

In an era where conversations about racial justice and equality have once again taken center stage, Juneteenth has gained a renewed relevance. As we grapple with the echoes of our past and the challenges of our present, Juneteenth stands as a testament to resilience, a beacon of hope, and an affirmation of progress. It reminds us not only of where we have been but also of where we must aspire to go. Now more than ever, Juneteenth’s story of liberation and perseverance needs to be amplified, for it is a story intertwined with the fabric of America itself.