The GI Bill—or The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, as it is more prosaically known—is one of the most important pieces of legislation in American history. It was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944 to help World War II veterans pay for college and buy homes. The bill has since been amended, expanded and renamed several times to include veterans of other wars and conflicts. Throughout it all, it has remained an important pillar of the American welfare state. This is its brief—and quite consequential—history.

Veterans benefits: the early years

In the early 1800s, the United States was a young republic with a small army; by the end of the century, it had become a major military power. Historians ascribe the stellar rise to the country’s developing economy, increasing population, and the widespread belief in Manifest Destiny, which held that it was America’s fate to expand across the continent. This led to several wars, including the Mexican-American War of 1846-8, which resulted in the annexation of California and the Southwest.

Unsurprisingly, American military service was originally built on British traditions. In time, these were adapted to serve the new republic better. Military commanders like Winfield Scott—aptly known as Old Fuss and Feathers for his strict attention to military discipline—brought a Prussian-modeled training program to the battlefields of the War of 1812. Along with the program, came also the tradition of rewarding the armed forces—not only during but also after service.

By the turn of the 20th century, US veteran payouts were going to survivors of several wars: the American Civil War, the American-Indian Wars, the Mexican-American War, as well as the Spanish-American War. All in all, even before the beginning of World War I, a basic delivery model for military recruitment and support for service members was firmly in place. But it wasn’t enough. At least not to meet the demands of the tumultuous 20th century.

The Bonus Act of 1924

American veterans returning from World War I got a different and seemingly better deal than their 19th-century predecessors. All war veterans—decided the US government in 1924, passing the Bonus Act—would be paid $1 for each day of active duty at home, and $1.25 for each day served abroad. The deal came with a catch: the bonuses couldn’t be redeemed for 20 years, that is not before 1945.

The participation of the United States in the Great War of 1914-1918 had been late coming, but it was still vital to the victory of the Entente Powers. It involved an unprecedented number of people in uniform for Uncle Sam: nearly four and three quarter million people were entitled to a war pension in line with the Bonus Act, more than all of the previous wars combined.

Most of these veterans, however, were happy only for a very brief period of time. It wasn’t the law itself that was the issue—it was the world. In the years between the passing of the Bonus Act and the redeemability of the bonuses, the world changed—and it changed irretrievably. For the worst.

The benefits model breaks down

In 1917, the future veterans of World War I left their cozy lives on one side of the Atlantic to fight for their country on the other—and came back two years after as heroes. Just a decade later, they were nothing more than strangers in their own, ever stranger land.

On Tuesday, October 29, 1929, the stock market crashed, and in the blink of an eye, the American dream was dead. The Great Depression had begun, and with it came a wave of despair that would sweep across the country and change it forever.

For the veterans of World War I, the crash was especially devastating. They had returned from the war expecting to pick up where they left off, but instead found themselves unemployed, homeless, and hopeless. Many of them turned to alcohol and drugs to numb the pain, and some even took their own lives. The rest joined forces and decided, in the summer of 1932, that enough was enough.

The Bonus March of 1932

In the summer of 1932, some 20,000 World War I veterans, accompanied by their partners and close families, marched on Washington to demand their government-promised bonus payments. The veterans were desperate for the money, and they were not going to wait any longer—and certainly not to 1945.

The Bonus March—as the march is known today—eventually turned into a riot, and the veterans were dispersed by government troops and tanks, commanded (quite regrettably) by several future war heroes such as Douglas MacArthur and George S. Patton. Two veterans were killed, and more than a hundred were wounded. Not only that, but the government did not give in to the veterans’ demands for years, and the bonus payments were not made until 1936, when the Adjusted Compensation Payment Act was passed.

The act—which authorized the early payment of bonuses to World War I veterans—is often considered a part of the New Deal, but it was actually vetoed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He argued that the country could not afford the bonuses, and that they would be inflationary, further adding to the federal government’s debt. In the end, however, the veto was overridden by Congress, and the bonuses—amounting to about $2 million—were paid out in full, with immediate effect.

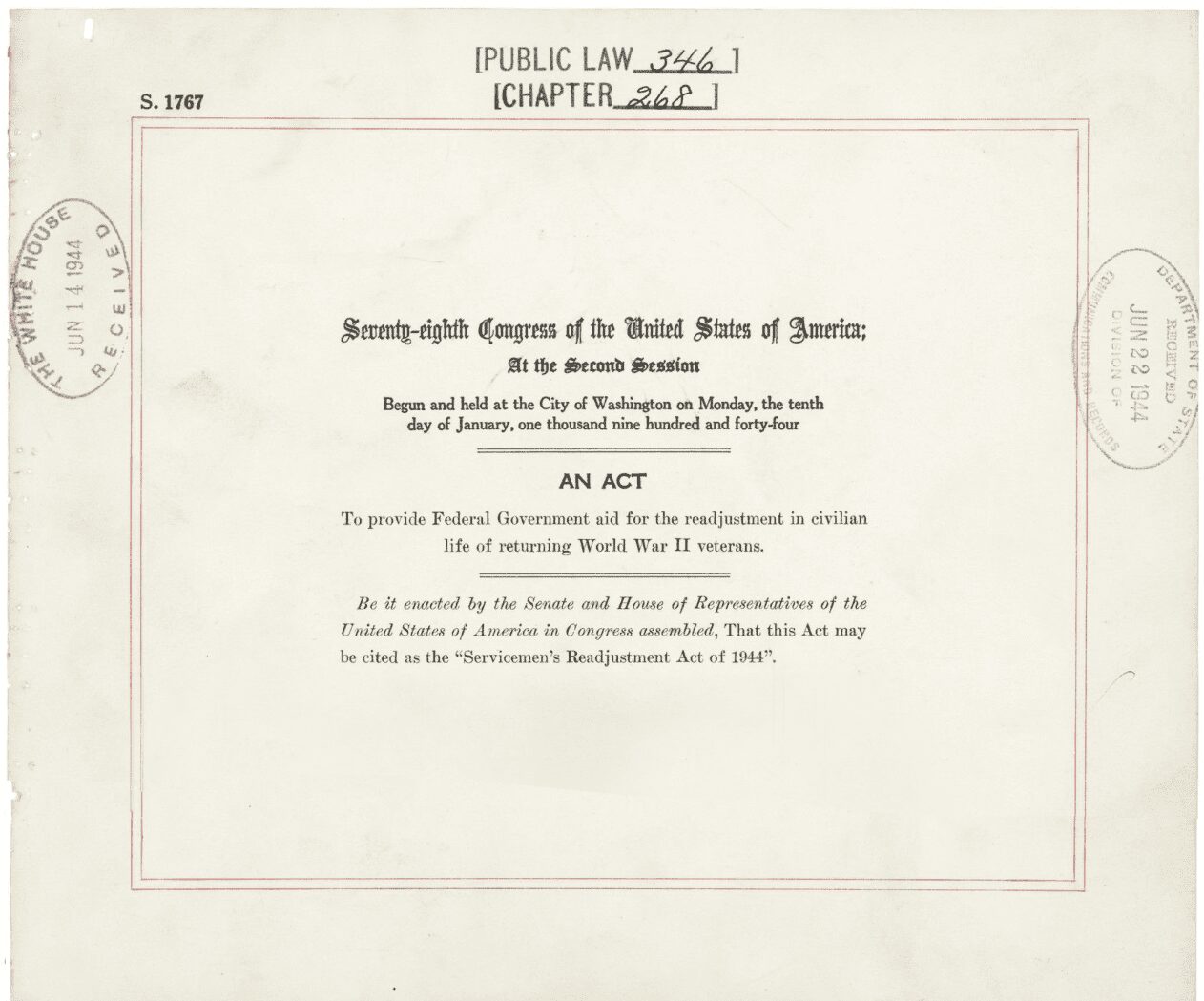

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944

By 1944, the final year of Roosevelt’s presidency, 16 million Americans were in uniform, participating in World War II. Determined not to let history repeat itself, the government proactively prepared for the veterans’ returns. To this end, in 1944, President Roosevelt signed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, one of the most important American documents of the 20th century.

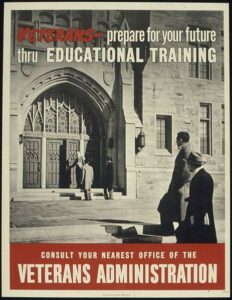

One of the backbones of Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act—commonly and popularly known as the GI Bill of Rights—aimed to provide federal government aid to US veterans to help them reenter civilian life as quickly and as effortlessly as possible. It provided numerous advantages for them, including specialized hospitals, floated low-interest home loans, job training, college educational benefits, and unemployment insurance. The government also set up the Veterans Administration—now the US Department of Veterans Affairs—to help manage and administer these programs, many of which live on through the present.

The GI Bill of Rights was a turning point in US history. Through it, for the first time, the United States government took full responsibility for the welfare of its veterans. This was a significant change from previous administrations, which had left the burden of readjustment to civilian life squarely on the shoulders of the veterans themselves. Alongside several other documents, such as the Social Security Act of 1935, the GI Bill is considered an important stepping stone in the development of the American welfare state.

The aftermath for World War II veterans

Much like their World War I predecessors, many World War II veterans fared poorly on return. Not only were their old lives gone but also many of their jobs had long since been filled by better qualified workers. Moreover, the war had inadvertently contributed to the long overdue empowerment of women, so the very face of the labor market had changed as well—and quite profoundly too! The original GI Bill of Rights aimed to help US veterans comprehend the new reality better, and get involved as soon as possible.

Thanks to the GI bill benefits, school campuses were filled with war veterans throughout the late 1940s. Unfortunately, not everybody profited from the education benefits equally. The southern states remained segregated after the war, so tens of thousands of black veterans—who had qualified for the educational benefits—couldn’t or wouldn’t get them from the Veterans Affairs. First Nations, Hispanic and other minorities had just as much difficulty getting access to good schools, particularly advanced degrees in higher education. And without the right college education, their career aspirations remained limited.

The Civil Rights era ushered in new hope for many. At first, societal changes found their way as amendments to the original GI bill, and then several new and improved programs were introduced, such as the Reserve Educational Assistance Program, the Forever GI Bill, the Montgomery GI Bill, VetSuccess on Campus and others. Almost all countries in the world boast sophisticated support programs for their veterans, but only a few of them are as comprehensive and generous as those in the US. And all of that can be traced back to 1944, when the Roosevelt administration introduced the all-important GI Bill of Rights.