Most of us have at some time seen this famous and peculiar photo. A bird-like mask covers the face of a 17th-century doctor who is further swaddled in robes and bears a wide-brimmed and flat-topped plague doctor hat. Sporting a cane to complete the ensemble, the individual brings to mind a crow about to conduct a symphony. While that sounds sinister enough, the actual purpose of the costume was arguably more serious.

The costume was designed to protect doctors as they treated patients who were suffering from the plague—typically the bubonic plague, but plagues can be septicemic and pneumonic as well!).

Combining form and function

While the whole outfit seems like something that one might wear to dress a local scarecrow, the plague doctor’s outfit was simply the technology of the time and designed as a means of identification, protection, and utility.

Serious robes and a casual hat

Published in 1963, W.N. Hargreaves-Mawdsley’s A History of Academical Dress in Europe: Until the End of the Eighteenth Century advises us that Doctor-of Medicine chic consisted of donning academic robes (black, of course), which were often pleated in the back. The ensemble was completed by topping it off with a flat-topped, wide-brimmed plague doctor hat.

This plague doctor hat, made of waxed leather, replaced what typically went with the formal-robe attire, which traditionally had included a round, corded bonnet.

Score one for style, early Euro-doctors!

Enter the crow

We don’t mean Brandon Lee, of course, but rather the crow-like headgear that would help protect the doctor as he went about his daily work. While it certainly changed the ensemble from stylish to scary (and anyone who saw one of these doctors did indeed tend to panic), this strange addition to the outfit was purely for utility. The “beak,” for instance, acted as a primitive respirator. Designed to fit over the doctor’s nose, it included two holes for ventilation, and the space in between its tip and the doctor’s own nose was generally filled with flowers and herbs. Roses were common, for instance, although you could also find things like a vinegar sponge, lavender, perfume, or even the opium-based narcotic known as laudanum (because why not?! This is a plague!).

These substances were meant to nullify the efficacy of the “pestilent airs” which surrounded the victims in order to protect the physician, and often the robes, boots, and anything else worn by the physician would be well-steeped in herbal goodness. Glass coverings in the eye-holes provided further protection, but while we could find no verification of it, we imagine those tended to fog up rather quickly.

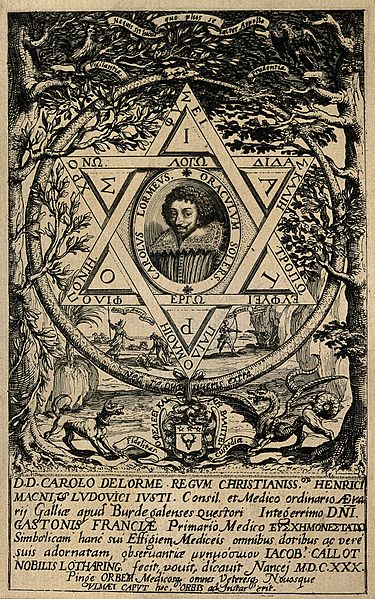

As far as its origins, this infamous incarnation of the plague costume is believed to have been devised by a Medici family physician, circa 1619, named Charles de Lorme. It was modeled from studies of the armor of soldiers of the day.

Purpose of the cane

The cane is another striking part of the costume—literally. One of its functions was simply keeping others away. While possibly the most ‘fun’ function (especially for the laudanum-beaked doctors), it was not the cane’s only function. The cane could be used also to point to objects or places of note, to remove patients’ clothes, or even to take a pulse.

So, did the plague doctor hat and costume actually work?

In a word, yes.

While to us, it may seem to be parts both frightening and hilarious. You need to keep two things in mind. First, newer generations tend to regard older technology and fashion as comical, and the plague doctor’s costume is from the 17th century!

Second, think about modern hazmat suits. The plague doctor’s outfit also included gloves, boots, leggings, an overcoat, and a hood for good measure, all of it waxed and herbed up to keep the plague out and the doctor safe. While the air filtration portion was the best attempt at “keeping out miasma” (essentially “diseased air”), the rest of the idea is sound.

Keeping covered and as insulated as possible from disease was the idea, and the plague costume delivered… they just didn’t have HEPA standards yet.