The Moon rusting is not something generally thought about. Simply because of the three elements required for rust to form, two of them aren’t supposed to exist on the Moon. It turns out; scientists might have been wrong. The recent analysis would suggest there is rust at lunar high latitudes.

Scientists now think Earth’s oxygen, dust particles, and the Earth’s magnetotail (more on that later) combine to provide the conditions for rust.

What is rust?

A rust-inducing chemical reaction forms when water and oxygen interact with iron. On Earth, it’s a common enough sight. Any surface iron deposit has long ago formed hematite (a form of iron oxide and the stuff they think is on the Moon) or one of the other forms of rust. Leave iron or any unprotected ordinary steel outside, and the telltale red will soon form.

On Mars, most of the surface is covered in iron oxide. That’s why it’s called the Red Planet. Long ago, Mars’ then water deposits combined with oxygen to interact with the iron-rich rocks on the planet’s surface and create rust.

But until the recent discovery of small ice deposits, scientists didn’t believe there was water on the Moon. And until a research team from the University of Hawaii looked at data from the Indian Space Research Organization’s Chandrayaan-1 mission, no one believed there was oxygen on the Moon either.

It starts with the Indian Space Research Agency

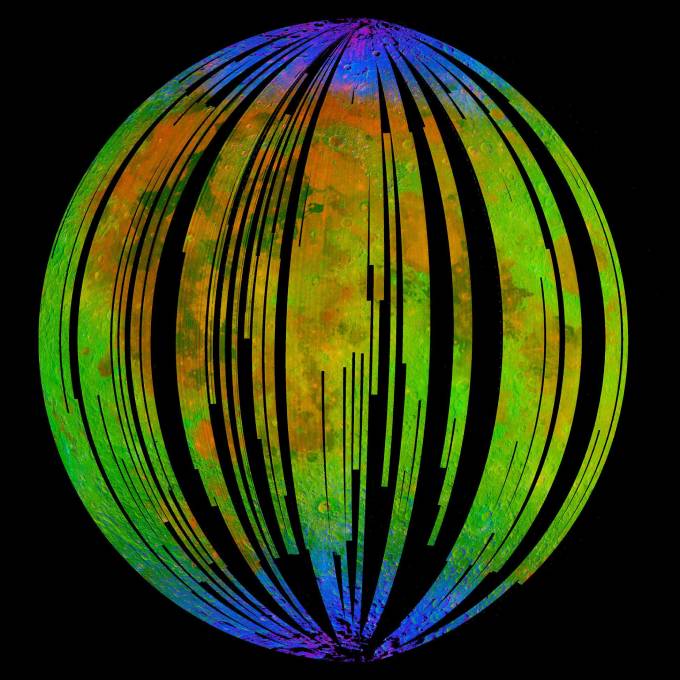

India’s first lunar mission, Chandrayaan-1, ceased operating in 2009 after a successful three-year lunar orbit. One of the instruments on board that mission, the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3), has resulted in some significant updates to our knowledge of the Moon’s surface.

Firstly, in 2018, the University of Hawai researchers discovered water ice deposits near the Moon’s polar regions. Away from the Moon’s Earth-facing side, these permanently shadowed craters of ice have hidden from scientists until the M3 gathered data.

Following this discovery, the researchers wondered whether water-rock reactions had taken place near the Moon’s poles. The new analysis of the M3 data would suggest that’s the case with quite extensive hematite deposits on the lunar surface.

So, where’s the oxygen?

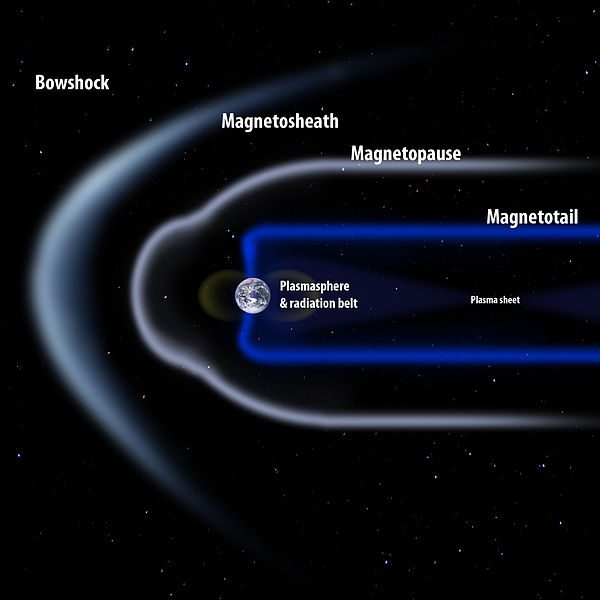

This is where it starts to get complicated. Our planet’s magnetic field has an important job protecting us from the constant bombardment of solar wind and the associated energetic particles. The theory is that oxygen comes from Earth’s upper atmosphere. This includes an awful lot of hydrogen.

Hydrogen, which at first glance, is another reason the Moon is a terrible environment for iron oxide. Oxygen oxidizes metals, taking electrons from them and allowing rust. Hydrogen does the opposite and adds electrons, making it harder to rust. The Moon is almost always exposed to solar wind and a constant hydrogen stream. So, theoretically, it should be even harder to get rust on the Moon.

The magnetotail is not a superhero’s appendage

The keyword here is almost. Once every so often, the Moon passes through the Earth’s magnetotail. Our planet’s magnetotail is actually what it says on the tin. The Earth’s magnetic field, compacted by solar wind, forms a tail streaming out behind the Earth in the opposite direction to the sun.

As the Moon passes through the magnetotail, the barrage of hydrogen from the solar wind stops. Thus increasing the chances of rust.

And it is the magnetotail that also adds the missing piece of the puzzle, oxygen. Japanese researchers discovered that small amounts of oxygen are carried from Earth’s upper atmosphere to the lunar surface along the tail. Hydrogen is blocked, and Earth’s oxygen is provided, thus creating a small window where rust could form.

The Darkside of the Moon

Confirmation of this theory comes from the fact that more rust is found on the earth-facing side of the Moon than on the far side.

But further analysis of the M3 data brought up an interesting conundrum. The hematite doesn’t appear to be near the shadowed lunar craters that contain ice on the dark side of the Moon. They needed a new theory about the origins of the water.

Dusty Moon

In 2013, NASA launched LADEE, Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer. This mission confirmed a belief that the Moon is engulfed in a permanent dust cloud.

And it is this dust cloud that is providing the water. The rust researchers proposed that water molecules found naturally in the Moon’s topsoil (because it’s space, they don’t call it topsoil, rather lunar regolith, but it’s the same thing) are the water source.

The fast-moving dust particles kick up surface-borne water molecules from the lunar soil (not many, but just enough) to mix with the iron and oxygen. And voila, the conditions for rust to form are complete, and lunar hematite is created.

Sending future missions

Scientists are hoping to explore these and other chemical reactions in future exploration. NASA has plans for dozens of instruments to be sent to the Moon over the next few years. And the Artemis program will see the first crewed mission to the Moon in almost fifty years.

NASA’s jet propulsion laboratory is building a new version of the M3 moon mineralogy mapper. They will send it up to get more data, create an enhanced map of the Moon’s surface makeup, and confirm more complex chemical processes are happening in space than previously thought.

These new theories could also be helpful in investigating other iron oxide mysteries, such as how it forms on other airless bodies, such as asteroids.