There’s nothing cozier than a Scandinavian winter holiday. Think of cold weather and warm houses; think of twinkling lights, roaring fires, and chocolate-topped buns; also, think of Christmas goats. Wait… what?

No, it’s not a mistake. If, by any chance, you get invited to a family home in Sweden, Denmark, Norway, or Finland around the winter holidays, expect to see a small hay decoration, shaped like a goat and bound with red ribbons, hanging either by the door or on the Christmas tree.

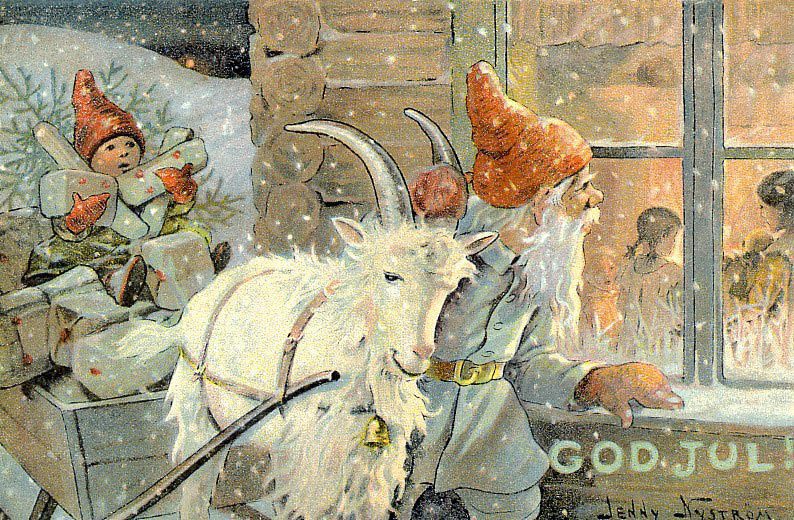

Well, this cute Christmas companion is called the Yule Goat. Nowadays, it’s become pretty much the Scandinavian version of Rudolph, but once upon a time, it was practically Santa himself. And long, long before that—all the way back to the Viking period—it was, well, a Jesus-like animal deity.

Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr: the story of Yule Goat’s origins

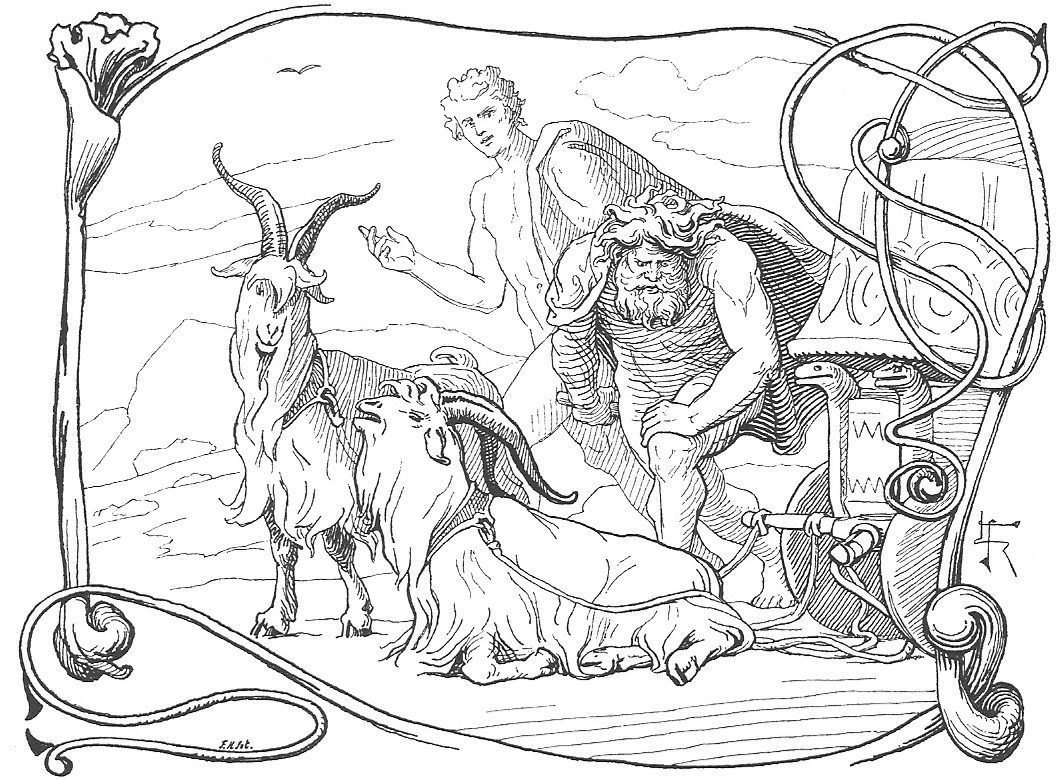

Though the Yule Goat’s origin is unclear, goats have been associated with pagan festivals for centuries. In ancient times, they were often sacrificed to the gods and used in fertility rituals—all over Europe. In Scandinavia, however, it is believed that the celebration of the Yule Goat must be somehow related to a particular deity: the Norse god of thunder, Thor. That’s because his chariot—as the medieval Eddas tell us—was famously pulled by two giant goats, whose names were Tanngrisnir (“Gap-tooth”) and Tanngnjóstr (“Tooth-grinder”).

The most well-known story about Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr—or, at least, the one that has probably influenced the tradition of the Yule Goat the most—can be found in the 44th chapter of a book called Gylfaginning (meaning, “The Beguiling of Gylfi”), which forms the first part of the Younger Edda, an immensely influential Old Norse textbook compiled by Icelandic historian Snorri Sturluson in the early 13th century. The story is quite brief and goes something like this.

On their journey to the Land of the Giants, Thor and the trickster god Loki—exhausted and bereft of sleep—decided to make a stop at the house of a poor farmer. After realizing that his welcoming hosts have no food to feed themselves, let alone their guests, Thor killed his beloved goats and flayed them, and then shared the goat’s meat with the farmer and his family. In the morning, just before daybreak, the god of thunder took his famous hammer Mjölnir, lifted it, and consecrated the goatskins. Lo and behold, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr were resurrected back to life!

Commemorating the Yule Sacrifice

Naturally associated with themes of rebirth and generosity, the story of Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr was eventually turned into an important community ritual. Under the name of juleoffer (“the Yule Sacrifice”), it has been attested as an important part of pre-Christian winter solstice celebrations over most of Scandinavia, but particularly on the territory of today’s Sweden.

As part of the festivities—some of which have remained alive to this day—a man dressed in goatskin and carrying a goat skull would play the role of Thor’s goats. After being symbolically killed by a group of revelers, he would give out a feast of goat meat to the community to symbolize the sacrifice of Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr. In the morning, a man playing the role of Thor would touch him with a hammer, and he would symbolically rise again—just like Thor’s goats in the days of gods and goblins, and just like the sun does every Yule.

Just like Jesus, for that matter.

Christianizing the pagan gift-bringer

For obvious reasons, early Christian fathers did not take to the sacrificial imagery of Juleoffer, and were quick to declare the julbock (“Yule goat”) a dark spirit or a demon—which was pretty much what happened all over Europe with many similar pagan gift-bringers, such as Iceland’s very own Yule Cat, Italy’s beloved witch Befana, and Germany’s misunderstood Krampus (himself a goat-like creature).

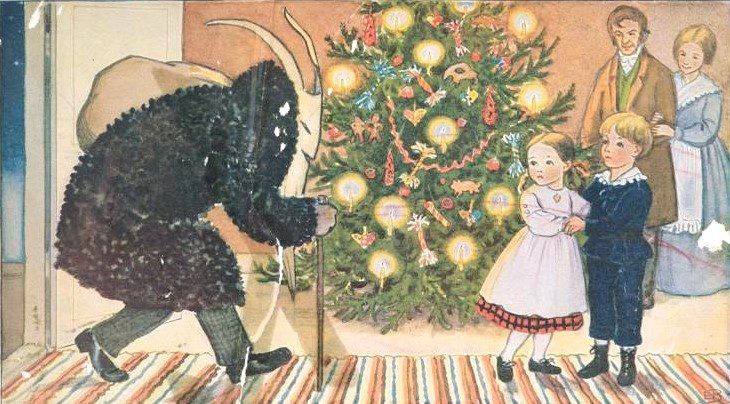

Indeed, there are quite a few Scandinavian stories from the early Christian period, reimagining the julbock as a frightening man-sized he-goat who, rather than giving away his meat to other people, demanded other people’s meat for himself, so as to satiate his voracious appetite. Before too long, this devil-like goat figure evolved even further to become nothing short of Santa’s helper. Originally, however, the now-festive image of Santa riding the Yule Goat was meant to symbolize the victory of Christianity over paganism, that is to say, Saint Nicholas’ control over the Devil.

Ancient pagan festivals and some modern festivities

By the time the 17th and 18th centuries rolled around—and rumors of evil goat spirits had died down—the Yule Goat made a festive return to the heart of Yule celebrations. Its pagan origins, however, have remained quite evident to this day.

For example, in some rural areas of Denmark, farmers still practice a juleoffer-like tradition. Come Christmas, a local farmer (known as gårdskarl in Danish) dresses up as a goat and then visits all the different Christmas parties around the village, one by one. Bursting through the door unexpectedly, he knocks over furniture, performs pranks, shouts obscenities, and delivers home truths to the party guests. For his antics, the gårdskarl is rewarded with food and money, the amount being dependent on the quality of his costume and the level of chaos that he’s able to stir up.

Related and even more famous is the custom of julebukking, another ancient Christmas tradition that has survived, in some ares, to this very day. Combining wassailing and Halloween trick-or-treating, julebukking sees many Scandinavians donning goat masks and walking around other people’s houses, singing songs and expecting some sweets in return for their efforts. These songs, however, aren’t Christmassy and jolly, but quite dark and obscene. Worth noting, Koliada is a strikingly similar Slavic tradition—even though it doesn’t necessarily feature goats.

Yule Goats on the Christmas tree

The days of goat skulls and truth-telling at Christmas have largely come to an end in Scandinavia today, and the festive season is now more of a family-friendly affair. That’s not to say that the Yule Goat is gone, but that he has evolved—once again—into a new, even more benign form. Indeed, the goat that most modern Scandinavians will know best is a popular Christmas ornament, made of straw and red ribbons, hung on the Christmas tree or near the front door.

Though the Yule Goat mostly serves a decorative purpose these days, in some households, elements of the pagan traditions that gave birth to it still remain. Namely, many Scandinavian families choose to write their wishes and messages for the New Year on their julbock, and then they hang them by the door to greet guests at the house. On New Year’s Eve, they will throw the goat in the fireside, performing a modern-day sacrifice, if you will, in the hopes that the New Year’s wishes will that way come true.

The Gävle Goat and his yearly struggle for survival

Though Yule Goats today are mostly hung in homes, the most famous is actually a public sculpture, erected each year on Castle Square in the Swedish town of Gävle. This Yule Goat has been a fixture of the town’s Yuletide celebrations since 1966 and is known for its awesome height: according to the Guinness Book of World Records, the Gävle Goat achieved its peak size in 1993, when it stood 49 feet (almost 15 meters)!

But, of course, no Yule Goat would be a true Yule Goat if there wasn’t some sacrificial element involved. Though the Yule goat was originally built as a spectacle to encourage people to come to bars and restaurants around Castle Square, it has consistently attracted chaos and mayhem—as seems only fitting. It all began with the very first Gävle Goat, which was burnt to the ground by unknown revelers on the strike of midnight, possibly as a prank.

Since then, the massive goat has been the subject of either attempted or successful vandalism each and every year, with 39 of the 79 Gävle Goats so far erected being either burned, torn apart, exploded, or even completely stolen. One year it was even destroyed by a group of young men dressed as Santa Claus, his elves, and other Christmas characters; on its 50th birthday in 2016, it was burned down just hours after its opening party!

Though not legal, attempting to destroy the Gävle Goat is now a popular Christmas prank and an unofficial ode to the old days of the Juleoffrer, Julebukking, and Gårdskarl running amok at Christmas parties, to the extent that the goat has never survived for more than three years in a row. For better or for worse, 2022 will not see the end of this unlucky streak, as the goat did not even survive until Christmas Day in 2021.