In the cold Icelandic winter and early spring, when snow coats the rugged hilltops and the lakes are glassy with ice, there’s nothing better to brighten the mood than a festival day. Indeed, Icelandic tradition has its fair share of celebrations that might seem a little strange to outsiders, from placating the prank-prone Yule Lads in the buildup to Christmas to worshipping a 49-feet (15-meter) high Yule Goat to rolling naked in the dewy grass on Midsummer’s night.

So, it’s not surprising that Icelanders have elaborate celebrations planned for the first three days of Lent, a time when carnivals and feast days are common worldwide. Enter Bolludagur, Sprengidagur, and Öskudagur: the three festival days that welcome Lent to Iceland.

Bolludagur (Bun Day)

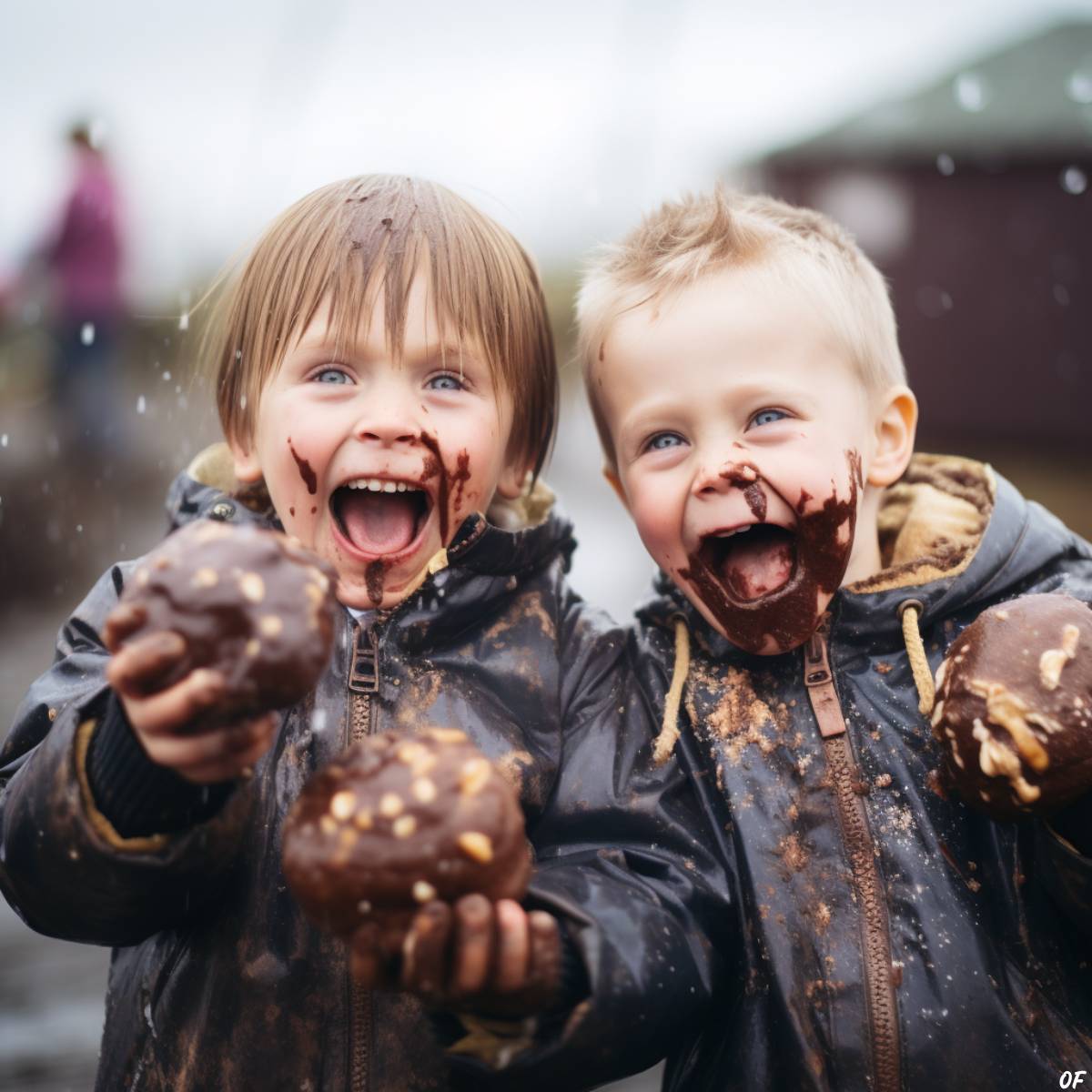

Bolludagur, meaning “Bun Day” in English, falls on the Monday before Shrove Tuesday. As the name would suggest, on this day, Icelandic children eat copious amounts of cream buns filled with jam and topped with chocolate icing. So popular is this festival that it’s estimated that Icelandic bakers cook around a million buns in the days leading up to Bolludagur, which is quite impressive for a country of only 366,000 inhabitants.

If you’re imagining polite little Icelandic kids sitting around a table waiting for their buns to be served, then you’d be very wrong! On Bun Day, kids need to earn their dessert. And they do so in the most fun way possible: by spanking their parents with a bolludagur—a wooden stick decked with colorful paper decorations on the end—as they scream “Bola! Bola! Bola!” to demand the coveted pastry buns. This custom is so old and widespread that the day used to have a name less appetizing than “Bun Day”—namely, “Spanking Day.”

Sprengidagur (Bursting Day)

Shrove Tuesday, the last day before Lent, is known worldwide as a day for indulgent eating, as families make excessive or elaborate meals to use up perishable ingredients before the traditional fast. With many famous feasting celebrations around the world falling on this day—most notably Britain’s Pancake Day and New Orleans’ Mardi Gras—it’s no surprise that there’s a unique Icelandic version of the holiday!

The name Sprengidagur literally means “Bursting Day” or “Explosion Day,” and it refers to the fact that Icelanders eat so much food on this day that they feel like they’re going to burst by the end of it. Typically, this large meal is a stew made of salted meat (usually lamb) and lentils or split peas, known as saltkjöt og baunir. Other ingredients include rutabaga, potatoes, carrots, and other vegetables that might otherwise go to waste.

Though this used to be a common meal that families would eat throughout the year, Sprengidagur is nowadays the only time most Icelanders eat this dish. Given that most Icelanders are irreligious, so they no longer fast during Lent, this meal has acquired a special secular significance—as a cozy little dish conjuring memories of childhood and family bliss.

Öskudagur (Ash Wednesday)

While Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, is associated with a long Christian tradition of prayer and piety, it’s all about dressing up and eating sweets in Iceland! On Öskudagur, most children dress up in costumes and go door to door and store to store, asking for candy. Sometimes they’d even sing and ask for treats as payment. So, imagine Öskudagur as a combination of Halloween and carol singing. In some parts of the country, kids get the day off school on Ash Wednesday because the candy route to their neighbors’ houses and stores is taken very seriously as an all-day endeavor.

Though no one is entirely sure where this custom came from, it’s assumed to be rooted in the Scandinavian tradition of Fastelavn, sometimes called “Scandi Halloween,” which sees costume-clad children pulling pranks for candies. It’s likely that certain aspects of this beloved festival—which is still celebrated in Denmark on the Sunday before Ash Wednesday—were brought to Iceland by Danish traders in the 19th century. Interestingly, Fastelavn might also be the origin of the Icelandic Bun Day tradition of children spanking grown-ups, since it usually features a piñata-like sweets-filled barrel.

Another mysterious aspect of Öskudagur seems to have been lost to time. Until recently, children would also try to hang little bags of ash and stones (called öskupoki) on grown-ups’ backs without them noticing. The victim would then have to walk through three doorways before they were allowed to remove the öskupoki from their back and get on with their day. The tradition actually began as a pastime for adults, who would try, in long times past, to hang ash bags on members of the opposite sex as a good luck message: the ashes from the palm crosses burning at the church were thought to be even purer than Holy Water. Fortunately, even when rituals die out, oral histories persevere. So we can, at least, tell the story.