You won’t find red-nosed reindeers or a benevolent Santa Claus in Icelandic Christmas folklore. What you will find is quite a few goblins, elves, giants, giantesses—and even a goat!

And then there’s also the cat. The child-eating Christmas Cat.

A different kind of Christmas night

Imagine Christmas Eve as a child. Playing games under the glittering Christmas lights. Shaking your presents to guess what’s hiding under the paper. The excitement of a visit from Santa Claus keeps you from falling asleep.

These are the images of Christmas that we are most familiar with in North America or Britain. Many other countries, however, have preferences for traditions that tend to invoke feelings not of joy and friendship—but of fear.

In Italy, for example, they have a gift-giving witch who, though kind and caring, would still whack you with her broomstick if you are unfortunate enough to see her. In France, that’s pretty much Père Fouettard’s only job: a companion of Santa, he does his dirty work, spanking the naughty children on Christmas Eve with a whip.

South Germany has a crotchety, fur-clad Santa called Belsnickel (yup, The Office didn’t exaggerate by much). In Alpine Central Europe, you’ll find an even more terrifying variation of him, an Anti-Santa of sorts, called Krampus. In Spain, they have the bizarre Caganer; in the Low Countries, the Black Pete; and in the Balkans, the malevolent Kallikantzaroi.

In Iceland—well, in Iceland, they have a child-eating cat.

The legend of the Yule Cat

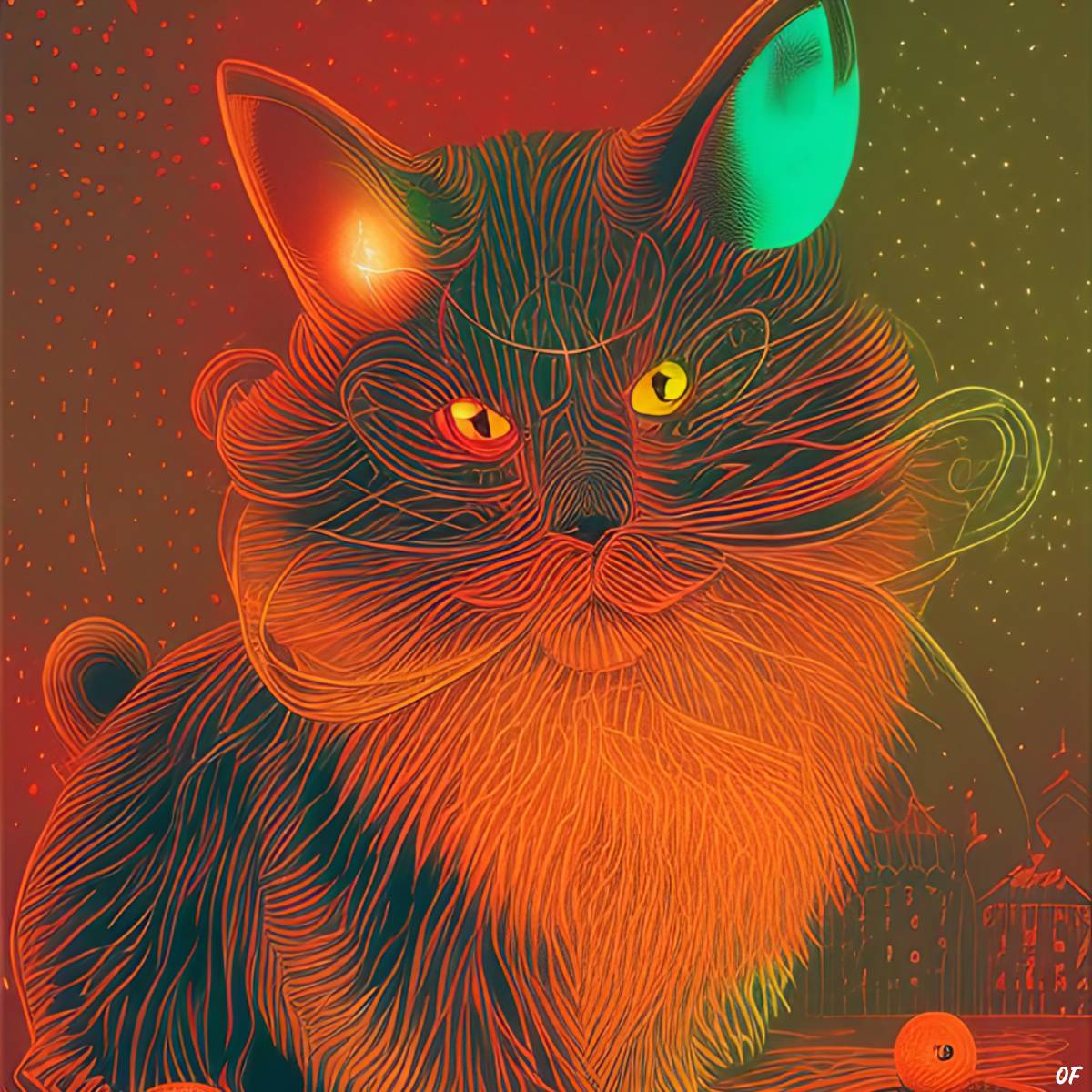

Iceland is best known for its rugged, snowy landscape, hot springs, and cozy cottages. But lurking in the dark on Christmas Eve is Jólakötturinn, or the Yule Cat, who peeks through windows and eats unlucky children who haven’t been given any new clothes as gifts for Christmas.

Jólakötturinn—from Jól (Christmas) and köttur (cat)—is described as a huge tomcat, with glowing eyes, sharp whiskers, and murderous claws. Come Christmas, he roams around the snowy countryside looking for his favorite food: naughty kids wearing tattered and torn clothes.

His legend is part of a catalog of folklore monsters designed to teach Icelandic children life lessons about how to survive the long, arctic winters and the dangerous wilderness. But we’ll get to that later.

The Yule Cat poem

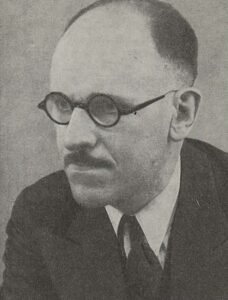

The most well-known account of the Yule Cat comes from a 1932 poem, written by one of the most famous Icelandic poets in history, Jóhannes úr Kötlum. The whole poem is quite long, and has only been translated into English in 2015, in free verse. We tried improving upon this, so you can get a better feel of the flow of the poem, in the original rhyming ballad meter. This is the poem’s opening stanza:

The Yule Cat, they say, everyone knows,

—it is such a colossal cat!

No one can tell whither he goes

or where he’s currently at.

Then there’s the memorable, blood-curling description of the Yule Cat:

His eyes are like chasms, huge and oblate,

blood-red and burning bright;

only the bravest can ever look straight

upon such a terrible sight.His whiskers are as sharp as his claws,

his back arches the sky;

hairy and heavy, his hulking paws

startle and terrify.He flutters and waves his powerful tail

he jumps, he hisses and claws:

sometimes he prowls up in the vale

and sometimes down in the snows.

What follows are some of the most frightening verses for children ever written:

He roams at large, hungry and vicious,

in the freezing hails of Yule,

peering through windows for something delicious,

his visage so scary and cruel.A pitiful “meow”, dead silence and then –

somebody’s paid the price:

the Yule Cat, they say, hunted for men

and did not care for mice.

A lesson to naughty children

The legend of Jólakötturinn is generally considered to be a moral tale to make sure that children finish all of their chores by Christmas. While a modern kid might end up on Santa Claus’s naughty list for throwing a tantrum or not tidying their room, for Icelandic children in the Dark Ages, helping the adults to make new clothes for winter was their most important job. For this reason, kids who were too lazy to finish their knitting would be left without anything new to wear at Christmas, exposing them to the appetite of the Yule Cat.

The fable also teaches the lesson of generosity. While the main moral is related to hard work and responsibility, it also suggests that good children who finish their work early could save their friends from Jólakötturinn by generously giving them a gift of new clothes, or helping them to finish their chores before Christmas Eve. In fact, at the end of the poem, Kötlum encourages listeners to give graciously to children who don’t have any new clothes, because not everyone enjoys the same advantages in life:

Now, if you know someone’s in need

of new clothes—heed the call;

since, perhaps, there’s somewhere a kid

who has, truly, nothing at all.And perhaps from the Yule Cat you’ll save them,

from their world, lightless and cruel—

it isn’t just clothes that you gave them

but a Merry, Merry Yule!

Why new clothes?

At this point in our story, there’s one thing you might still be wondering about: why new clothes?

From the Middle Ages, wool production was Iceland’s biggest industry, and a major part of life for most Icelanders. Even as early as the 1600s, Iceland was exporting not only raw wool, but hundreds of thousands of knitted wool products, including scarves, sweaters, socks, and mittens.

For ordinary Icelanders, wool and clothing production was not just a way of life, but a necessity for survival. Icelanders had to endure long, bitterly cold winters, during which the sun didn’t rise for months. Therefore, it was vitally important for everyone to have a full wardrobe of serviceable, warm clothes by the time the winter rolled in.

The whole family was involved in spinning, weaving, and knitting to make new clothes for the winter months. In this context, it seems only natural that some Icelandic parents invented the fable of a giant Yule Cat who eats children who don’t have any new clothes; after all, it was vital for the entire family that everyone had done their part in preparing for the cold season.

Evening storytelling sessions

The Middle Ages is seen as Iceland’s golden era for storytelling, an important aspect of Icelandic culture to this day. These evening knitting sessions were an important part of family bonding time, and someone would normally read or tell stories, known in Iceland as sagas, to entertain the family while everyone was busy making these new clothes.

In fact, partly due to the importance of family story-time, Iceland had a near-universal literacy rate by the end of the 18th century—the first country in the world to achieve the feat, far before the rest of the globe! To this day, Iceland is still a nation of readers and storytellers, with the highest rate of books published and novelists per capita in the world.

The origins of the Yule Cat

Historians are not entirely sure when the Icelandic legend of the Yule Cat was first told. It’s quite possible that Jólakötturinn was originally a Norwegian demon-companion of Saint Nicholas, much like Krampus or Père Fouettard, symbolizing all the evil forces of the world. In Dutch, for example, the name of this demon (and one of the many names of the Devil) is “Duivekater,” which almost translates to Devil’s Cat.

Be that as it may, it seems that the legend of Jólakötturinn wasn’t that popular before Jóhannes úr Kötlum published his influential poem. What’s interesting, however, is that it is not the only instance of an evil creature—or even an evil feline!—in Icelandic traditional storytelling: the character itself fits into a deeper background of mountain-dwelling trolls and giants.

The Yule Lads

At one time, Jólakötturinn seems to have been just a marginal character—the scary pet of the Yule Lads, the 13 mischievous sons of the troll Grýla and her lazy husband Leppalúði.

The Yule Lads drop in, one by one, during the 13 nights running up to Christmas. Expecting them, Icelandic kids place one of their shoes on the windowsill every evening, and get either a small gift as a reward for their good behavior, or a rotten potato as a punishment for their questionable conduct.

The legend, however, was not always so friendly. Originally, the Yule Lads were said to carry off naughty boys and girls away to the mountains to boil them in a pot. The tale was once deemed so fearsome that in 1746 the King of Denmark had to issue a regulation, outlawing “the foolish custom of scaring children with Yuletide lads or ghosts.”

The Wasteland Cat

Whereas the Yule Lads have had somewhat of a rebrand in recent history, their pet has continued to terrorize the boys and girls of Iceland, preserving some of that all-important Christmas fear.

The transformation of the Yule Cat from a marginal pet into a gruesome beast who eats people might have something to do with the Wasteland Cat, another monstrous Icelandic feline. (Fortunately, the werewolf cat is quite a recent cat breed—we don’t want to even think about in what way it could have inspired Scandinavian Christmas traditions had it existed back in the Middle Ages!)

According to Icelandic legend, the Wasteland Cat (or Ghoul Cat, Urðarköttur) burrows underground, usually in a cemetery, as a kitten, and stays there for three years. When it is fully matured, it leaves the graveyard for the rocky Icelandic mountains, where it attacks people and eats any living thing it might find, most commonly sheep, birds, and humans.

Its most intimidating superpower is its evil gaze, which is said to be able to kill anyone who makes eye contact with her—kind of like a feline Medusa!

Jólakötturinn today

The Icelandic legend of the Yule Cat is still well-known and loved today. In 2018, the city of Reykjavík commissioned a 16-foot (5-meter) tall, 19-foot (6-meter) long statue of Jólakötturinn, which lights up during Christmas time to honor Iceland’s culture of storytelling and wool production.

Just as memorably, in 1987, the country’s best-known singer Björk recorded a version of Jóhannes úr Kötlum’s classic, and then a few years later recorded a version in English translation. The song is one of the most well-known and loved Christmas songs in Iceland to this day, as it captures the iconic essence of Icelandic Christmas folklore.