A simple misunderstanding is, of course, just that. The origin of “Indian giver” is a much darker story in which a cultural misunderstanding became a slur, spawning stereotypes, and prejudice. It is one of history’s most twisted examples of tragic irony.

Gift reciprocity is a vital custom woven into the fabric of Native American communities. It establishes balance within societies, reinforcing a sense of mutual support. Native Americans couldn’t have known that sharing their customs would have such grim consequences far beyond name-calling.

A playground taunt with weight

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines an “Indian giver” as:

A person who gives something to another and then takes it back or expects an equivalent in return (dated, offensive)

It’s worth noting that only within the last decade was it deemed “offensive”—an upgrade from its previous status as “sometimes offensive.”

“Indian giver” was widely considered little more than a harmless tease used by children. This correlation between the phrase and juvenile behavior is ingrained in its demeaning history. At its core, “Indian giver” insinuates that a person is uncivilized.

Moreover, calling someone an “Indian giver” implies they are deceitful. It’s hard to miss the absurdity of its misuse as a judgment about Indigenous people, not the colonists. Chair of Native American Studies at Dartmouth College Melanie R. Benson sums it up succinctly:

Not only were Natives’ earliest contributions of skins, husbandry, and agricultural tutelage unreturned, but their very lands formed a gift-wrapped package of lucrative opportunity for waves of European settlers who continued to take and take until virtually nothing was left for the exploited ‘givers.’

Origins in cognitive bias

The first definition of “Indian gift” appeared in 1765. Governor of the Massachusetts Bay colony Thomas Hutchinson described the phrase in his book History of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, stating:

An Indian gift is a proverbial expression signifying a present for which an equivalent return is expected.

This woeful ignorance of Indigenous customs was consistently reinforced in the coming decades. Historian and author Thomas P. Slaughter wrote that even famed explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark found gift exchange with Native Americans problematic throughout their expedition west in 1804. This contrasts the endless accounts of lifesaving generosity from the local tribes, and of course, their Shoshone guide, Sacagawea.

The 1848 Dictionary of Americanisms by John Russell Bartlett further cemented the phrase in American colloquial language, linking it to childlike conduct:

When an Indian gives anything, he expects to receive an equivalent, or to have his gift returned. The term is applied by children to a child who, after having given away a thing, wishes to have it back again.

Normalizing a stereotype

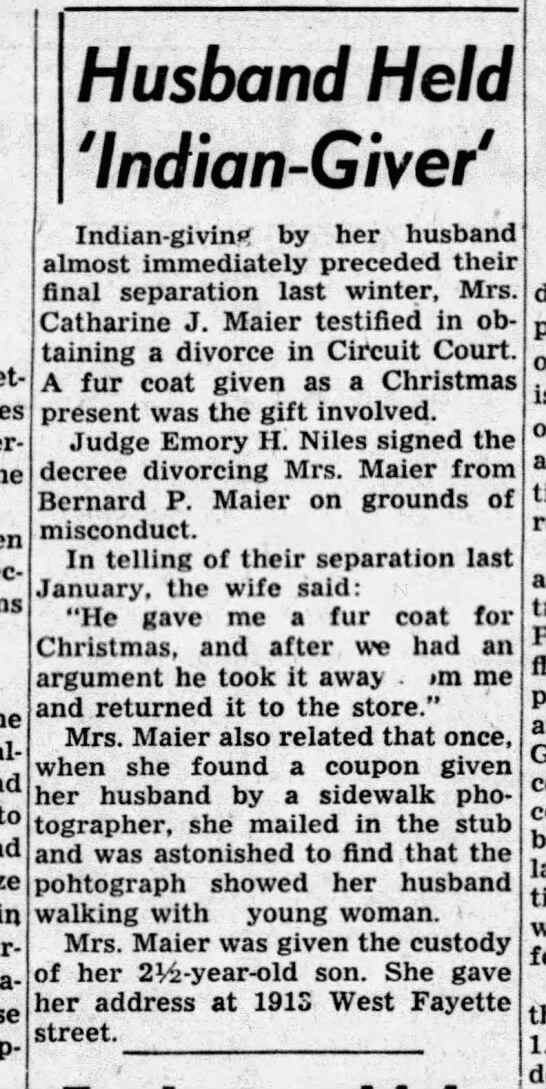

During the 1900s, “Indian giver” solidified its place in American lingo. It became a favorite go-to in describing squabbles over personal property during a breakup or divorce.

The story of a husband demanding his wife return gifts during their divorce was covered under the headline “Indian Giver, Says Ex-Wife, Of Hubby” by the Detroit Free-Press in 1919. The Los Angeles Times described an actresses’ triumph over her ex in keeping the house as “Indian Giver Defeated in ‘Dream House’ Suit” in 1930. The phrase even found its way into music with the 1969 pop song “Indian Giver” by the group 1910 Fruitgum Company.

By the 1980s and ’90s, increasing cultural awareness reframed common language with deeper context. In 1993, the popular TV sitcom Seinfield aired an episode featuring the phrase as part of a wider commentary on stereotypes and racism. Nonetheless, several more references years later would raise eyebrows. In one high-profile case, reality TV star Kris Jenner resurrected the phrase in 2011 when her ex-son-in-law requested the return of a $2 million engagement ring from Kim Kardashian.

Executive Director of the National Congress of American Indians Jacqueline Johnson Pata issued this response:

Once again American Indians and Alaska Natives have been misrepresented by a single misinformed statement. … The phrase ‘Indian giving’ is wrong and hurtful. The cultural values of Native Americans are based on giving unconditionally and empowering those around them. Instead, this cultural value is forgotten when negative stereotyping of Native people occurs.

A circle of giving in the Native community

Cross-cultural communication is vital in a globalized world. In the ominous march of manifest destiny, understanding foreign ways is not a priority.

The concept of gift reciprocity is fundamental in Native American culture. Understanding the customs of giving and receiving reveals the startling short-sightedness of the European settlers. In Native American Philanthropy, Kate Kozen writes:

Giving is not only understood to be reciprocal but is also an honor; as much as it is an honor to give, it is equally an honor to receive. Because it is such an honor to receive, there is also, in turn, an obligation to give. Thus, the Native American idea of giving and receiving is cyclical.

Founder of the First Nations Development Institute Rebecca Adamson explains that reciprocal giving is about interconnectedness. Ceremonies such as feasts and potlaches are traditional celebrations of giving, collective sharing, and restoring wealth balance within a tribal nation. Adamson describes giving practices amongst Native Americans as both cultural tradition and a community obligation. Her poem, Indian Giver, speaks to the role of reciprocity in strengthening communal bonds:

Let there be no purpose in receiving save reciprocity.

For a society whose belief in humanity lies within the interdependence of people

Who hold to the deeply universal good of community values and

Where children are the generation of our People

Giving is seen in the entirety of receiving.

Returning ‘Indian gift’

The phrase “Indian giver” distorted a concept that forges trust and cooperation rather than destroying it. This deteriorated into a stereotype that amplified unfounded prejudices about the treachery of Indigenous peoples. The horror of atrocities committed against Native Americans cannot be overstated, making the legacy attached to this phrase tragically ironic. Some are now choosing to reclaim it.

For their art exhibition confronting cultural appropriation, artists Erika Iserhoff and Sage Paul chose Indian Giver as a “cheeky title.” Iserhoff linked the derogatory term to the colonization that devastated Indigenous communities, from the theft of resources to the theft of culture for profit:

We shared our knowledge, and we shared our wealth, in hopes that it would be reciprocated, but it wasn’t. We helped people survive, and all they did was basically steal, but we’re the ones called the thieves.

The First Nations Development Institute’s quarterly newsletter is named Indian Giver, a choice they also referred to as “tongue-in-cheek.” The newsletter details the nonprofit’s work in facilitating grants that support Native communities. Communications Director Amy Jakober explains that in addition to having a culture of humor at First Nations, they use the name with intention:

As the practice of Indian reciprocity has been (and still is) terribly misunderstood, First Nations sees the name as an opportunity to put the phrase Indian Giver back in front of folks, demonstrating that the practice of Indian Giving is a positive thing.

“Indian giver” is one piece in the broader story of exploitation. Any power in reclaiming the phrase feels dwarfed by the enduring subjugation Native Americans experience to this day. We have far to go in healing trauma past and present, but maybe there is an inherent lesson in the truth behind “Indian giving” that was once so quickly dismissed.

In the words of Rebecca Adamson’s Indian Giver:

Giving is not a matter of pure altruism and benevolence

But a mutual responsibility

To make the world a better place.