In the world of politics, every word matters—just a single misinterpreted phrase, or even a casual translation mistake, can have massive ramifications and cause irreparable damage. By all accounts, one such incident occurred in 1945, when a mistranslation of the Japanese term mokusatsu led to one of the most consequential diplomatic blunders in history.

Seemingly slight, the incident changed the course of the world, and serves as a reminder of the importance of accurate translation—as well as a cautionary tale about the potential implications of misinterpretation.

The context: 1945 in brief

1945 was a decisive year in World War II. In Europe, the Allied powers began their final push toward complete victory. Following the Red Army’s capture of Berlin, and the death of Adolf Hitler at the end of April, Germany unconditionally surrendered on May 8th. This marked the official end of the war in Europe.

In the Pacific, the United States and its allies were making steady progress against Japan. In the spring, American GIs had invaded Okinawa and Iwo Jima, and by midsummer had recaptured the Philippines. Japanese forces continued to fight fiercely, however, and the war dragged on.

In order to prevent further loss of life, on July 26, the United States, United Kingdom, and China issued the Potsdam Declaration, an ultimatum demanding Japan’s unconditional surrender. The fate of the war, and the future of Japan, was now firmly in the hands of the Japanese prime minister, Kantarō Suzuki.

The Potsdam Declaration

As agreed upon at the Potsdam Conference, the Potsdam Declaration stated that the Allies would accept nothing less than the unconditional surrender of Japan, and demanded that the Japanese government “shall remove all obstacles to the revival and strengthening of democratic tendencies among the Japanese people.”

In addition, the Declaration set out the terms for postwar Japan, including the occupation of the country by Allied forces and the establishment of a new government based on “the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” Finally, it also called for the disarmament of the country, and the return of all Japanese army troops from occupied territories.

“These are our terms. We will not deviate from them. We will brook no delay,” the Declaration stated unequivocally, ominously ending with the following ultimatum:

We call upon the government of Japan to proclaim now the unconditional surrender of all Japanese armed forces, and to provide proper and adequate assurances of their good faith in such action. The only alternative for Japan is prompt and utter destruction.

The Japanese response

The Potsdam Declaration became known to the Japanese authorities at a time when they were already moving toward surrender. Among other things, they had attempted to secure intervention from the Soviets, in order to bring about an agreement with the United States. All the Declaration did was make it clear that their efforts had failed.

Even so, the Japanese government was divided on how to respond to it, not the least because of the significant difference between its terms and the terms of surrender imposed upon Germany. Some members of the government, including prime minister Suzuki and Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō, advocated for accepting the terms, while others—such as War Minister General Korechika Anami—argued for continuing the war.

Ultimately, they agreed to neither accept nor reject the declaration, and instead—at a July 28, 1945 press conference—publicly adopted a policy of “silent criticism,” a policy of mokusatsu. “But here,” Kawai writes, “the Japanese language played a fateful trick on the government’s decision.”

The word itself: mokusatsu

First published in 1918, Kenkyusha’s New Japanese-English Dictionary is widely considered the largest and most authoritative dictionary of its kind in the world. If one had opened its 3rd edition to page number 1129 and searched for the entry for mokusatsu, one would have found the following definition:

mokusatsu 黙殺—suru, v. take no notice of; treat (anything) with silent contempt; ignore [by keeping silence]; remain in a wise and masterly inactivity.

The dictionary entry makes several things clear. First of all, that mokusatsu is a complex term, composed of two kanji characters: 黙 (moku, meaning “silence”) and 殺 (satsu, “killing”). Secondly, that it has no exact equivalent in the English language. Thirdly, it shows that mokusatsu is an ambiguous word, which has a range of different applications and interpretations. Finally, it reveals that some of these are quite different from the others.

When Japanese prime minister Suzuki used the word mokusatsu in the month of July 1945, what he was probably trying to say was something along the lines of, “Regarding the declaration, for the time being, we’re withholding comment.” However, that’s not how his words were actually translated.

The worst translation mistake in history

All things considered, the Japanese leadership had not intended to be dismissive of the Allied demands; rather, they were simply being cautious and wanted time to consider their options. Unfortunately, their intention was lost in translation, leading to a diplomatic disaster with far-reaching consequences.

You see, when prime minister Suzuki’s words were first translated into English, the mokusatsu-part took the following form: “The government of Japan has no other recourse but to ignore this declaration entirely.” There were no footnotes, no mention of other meanings. There was just this one translation.

True, Japan’s propaganda agencies were partly to blame for this, as they wanted to save face and so tried to spin the response as a defiant refusal. Mokusatsu can mean that too. However, by the time Foreign Minister Tōgō realized the Prime Minister had been misinterpreted, it had already been too late. The damage had already been done.

Angered by the tone of Suzuki’s statement—and seeing it as yet another example of that well-known kamikaze-driven fanatism—US officials decided to take stern measures. The sternest.

The devastating consequences

In retrospect, the Allies were never given a reason to believe that Japan had not intended to be disdainful. To them, mokusatsu could mean one and one thing only: a silent, deliberate refusal. Rather than reading it as “no comment,” they could only read it as “not worthy of comment.” This was no insinuation of any kind on part of Suzuki; it was a forthright insult.

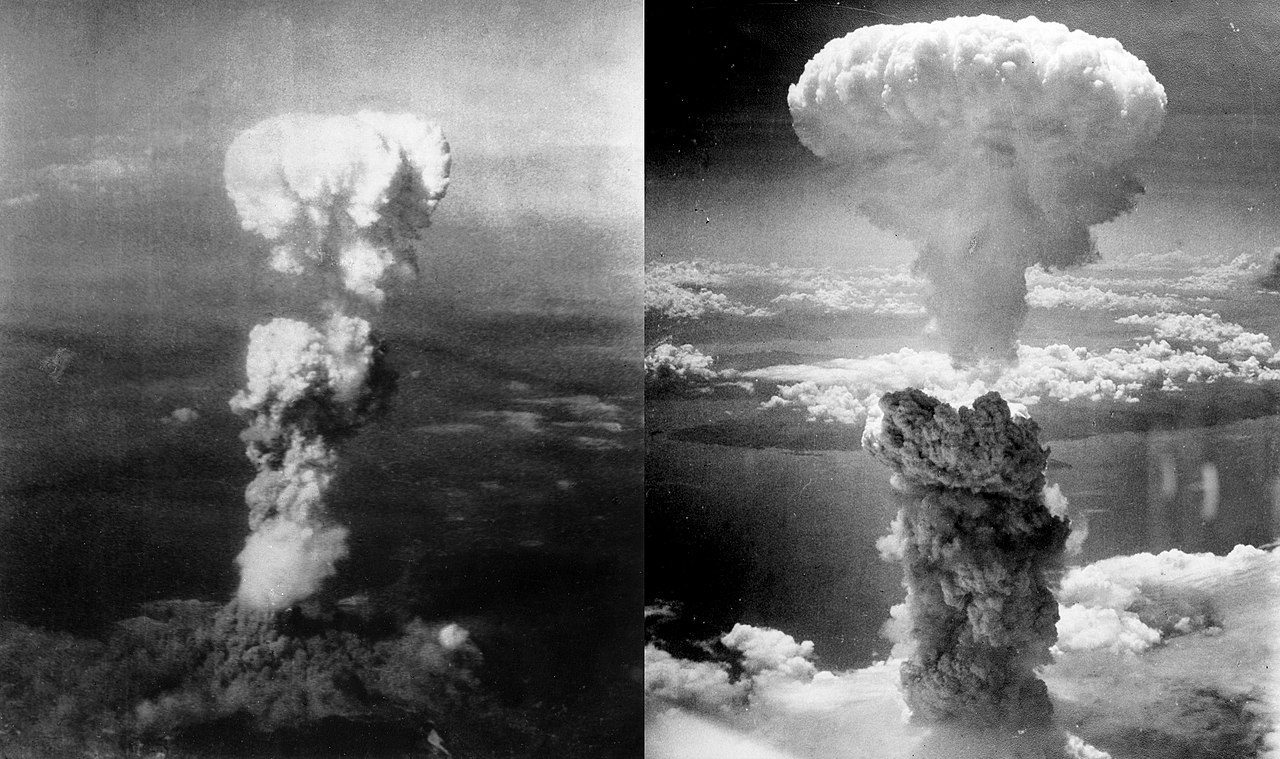

The consequences of this misunderstanding were catastrophic. Within 10 days, the US decided to do something no other country had ever done before: drop atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And on August 6 and August 9, 1945, they did just that.

This marked a devastating and tragic moment in human history. Over 200,000 people were killed in the two cities, with many more injured and made homeless by the blasts. The shockwaves of the bombs’ detonations were felt for miles around, and the aftereffects of radiation sickness, cancer and birth defects are still seen today.

The horror of the bombs’ destructive power was seared into the memories of all those who witnessed it, and served as a stark warning to all mankind of the destructive potential of nuclear weapons. Little did anyone know at the time that it was also a severe reminder of something else entirely—that even the smallest of misunderstandings can have devastating consequences.

The birth of the story

When Hiroshima and Nagasaki were reduced to rubble, Kazuo Kawai—future lecturer in Far Eastern history at Stanford University—was editor of the Nippon Times of Tokyo. Sensing that “something significant was afoot during those days,” he supplemented the coverage of his staff by personally spending “several hours each day in the Japanese Foreign Office.”

Due to wartime censorship, he wasn’t able to publish the notes thus collected until November 1950, when his article, “Mokusatsu, Japan’s Response to the Potsdam Declaration” appeared in the scholarly journal Pacific Historical Review. In it, Kawai argued that the mistranslation of mokusatsu as “treat with silent contempt” was a key factor in the Allies’ misperception of Japan’s true intentions, paving the way for the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This was the first time ever that such a perspective was presented to the public, and especially the English-speaking world. Between 1945 and 1950, the Allies had been unanimous in their interpretation of mokusatsu as an act of defiance, with no one questioning the prevailing narrative. Kawai’s article offered new insight, and sparked academic debate on the topic.

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend”

In 1953, in a widely read article published for Harper’s Magazine, American novelist William J. Coughlin popularized Kawai’s idea across the United States. The story was quickly taken up by the media and other prominent journalists, and very soon that small word mokusatsu became a widely-recognized term for a major diplomatic misstep.

However, what firmly enshrined the word in the annals of diplomatic and linguistic history was a 1968 article published in none other than the NSA Technical Journal. In it, Harry G. Rosenbluh—cryptologic linguist and translator-checker at the US National Security Agency—tangibly endorsed Kawai’s views, and in so doing, effectively created a permanent legacy for the term.

However, to this day, nobody really knows if mokusatsu was misused, misunderstood, or neither. While it’s true the controversy continues to be debated to this day, the consensus among scholars seems to be that Suzuki’s statement was actually unambiguous when analyzed in its entirety, and that he was understood properly by the Allies. Regretfully, even if that’s not the case, it is unclear if the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could have been avoided.

“What we’ve got here is failure to communicate”

A tragic fact of war or a retcon-driven Japanese legend, the story of mokusatsu continues to endure, not the least because it sounds like a modern-day parable. As Rosenbluh argued back in 1968, its obvious lesson is that cross-cultural translation is difficult and that this is doubly true in the world of politics. “Choosing the wrong meaning of a word or failing to inform a decision-maker that there are nuances to it could well have unexpected repercussions,” writes Rosenbluh.

But there’s also another lesson hidden here, and perhaps that’s the more important one. Namely, that in cases when one doesn’t want to be understood, one must try to use words that are precise and unambiguous. As Rosenbluh explains, contrary to popular opinion, mokusatsu isn’t a story about the worst translation mistake in history, but about the worst intentional use of language.

For more reasons than one, the concluding paragraph of Rosenbluh’s article deserves to be ours as well:

Some years ago I recall hearing a statement known as “Murphy’s Law” which says that “If it can be misunderstood, it will be.” Mokusatsu supplies adequate proof of that statement. After all, if Kantarō Suzuki had said something specific like “I will have a statement after the cabinet meeting”, or “We have not reached any decision yet”, he could have avoided the problem of how to translate the ambiguous word mokusatsu and the two horrible consequences of its inauspicious translation: the atomic bombs and this essay.