When the body of a 2,200-year-old noblewoman from a tomb in Mawangdui, China, was discovered, they could scarcely believe their eyes. Lying before them was an ancient mummy so well-preserved that it defied the ravages of time. This was Xin Zhui, also known as the Lady Dai, an aristocrat of the Han Dynasty, whose life and death have been the subjects of intense study and fascination ever since. With a preservation state akin to someone who had recently passed away, Xin Zhui’s body has been regarded as one of the world’s best-preserved mummies, an anomaly that continues to stun scientists and archaeologists alike to this day.

This seemingly time-immune body was none other than that of a rich, influential woman from an era long past. The wealth and importance of Lady Dai were reflected in the opulence of the artifacts found within her tomb, which paint a vivid picture of the indulgent lifestyle she led. Despite her deterioration due to exposure to oxygen, she remains in a reasonably preserved state, providing an unprecedented opportunity to delve into the life, lifestyle, and medical history of a person who lived over two millennia ago.

What factors contributed to the exceptional preservation of Xin Zhui? Why has she managed to survive in such a condition while other bodies buried in similar environments failed? The story of Lady Dai is more than just the tale of a mummy; it’s a scientific mystery that is waiting to be unraveled. As we delve into the world of Lady Dai, we venture on a journey to understand the extraordinary preservation of her body, her life as an elite in the Western Han Dynasty, and her eventual death, all reflected in her meticulously preserved remains.

Discovery of the tomb

The discovery of Xin Zhui’s tomb revealed a story of serendipity. In the 1960s, a group of construction workers in Mawangdui, near Changsha, China, unwittingly stumbled upon an archaeological treasure trove. Little did they know that their routine work would lead to the unearthing of one of the most significant finds in the history of archaeology.

The site was painstakingly excavated by archaeologists and hundreds of local schoolchildren in the early 1970s. They revealed a trio of tombs belonging to the family of Li Cang, the Marquis of Dai, who held considerable power during the Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE).

Amidst this necropolis, Lady Dai, the wife of Li Cang, was interred in a tomb separate from her husband’s. The tomb was a veritable time vault, filled to the brim with thousands of artifacts that bear testament to the opulence of their lives. Among the treasures were delicate silk manuscripts, lacquered vessels, and even traditional herbal medicines made from ingredients such as cinnamon, magnolia bark, and peppercorns.

Yet, the crowning glory of the find was undoubtedly the body of Xin Zhui herself. Her remains, remarkably well-preserved compared to those of Li Cang and a younger man, possibly their son or Xin Zhui’s brother, found in a third tomb, became a focal point of interest and intrigue, the mysteries of which we continue to investigate to this day.

Physical condition and examination of the mummy

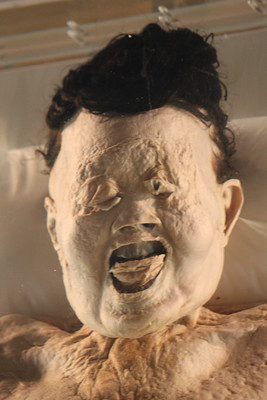

Upon discovering Lady Dai, the preservation of her body stood as an exceptional testament to the embalming prowess of the ancient Han dynasty. This millennia-old mummy exhibited astonishingly fresh traits that left scientists both bewildered and fascinated.

The mummified Xin Zhui, bore uncanny resemblances to a recent cadaver rather than a relic from antiquity. Her skin was found to be soft to the touch, still retaining its suppleness even after 2,100 years. Contrary to the typical rigidity encountered in most mummies, Xin Zhui’s joints remained flexible, her limbs capable of bending.

However, it was the internal examination that truly unveiled the astounding condition of Lady Dai’s body. Her veins were found to still contain congealed blood, and her organs remained intact. This unprecedented level of preservation allowed pathologists to perform a detailed autopsy, revealing a wealth of information about her life and health.

The findings of the autopsy told a tale of luxury and excess. From the undigested muskmelon seeds in her stomach, it was apparent that Lady Dai indulged in a meal shortly before her death. But beyond the minutiae of her final meal, the examination shed light on a slew of health issues that plagued her. Among these were obesity, coronary heart disease, diabetes, and gallstones—ailments primarily linked to a sedentary and lavish lifestyle. A Chinese scientist noted, “she probably did not need to exert herself,” a remark pointing to her noble status and the resultant lack of physical exertion.

Moreover, the autopsy unveiled details as specific as her blood type—Type A. Xin Zhui’s autopsy is arguably the most complete medical profile ever compiled on an ancient individual. The breadth and depth of the information gleaned from her remains paint a vivid portrait of the noblewoman’s life, lifestyle, and health—a testament to her enduring legacy as the best-preserved mummy in human history.

Preservation techniques

The survival of Xin Zhui’s remains in such remarkable condition is owed to an amalgamation of sophisticated preservation methods applied during her burial. The preservation techniques were manifold, each playing a significant role in creating an environment conducive to preserving her body for over two millennia.

Lady Dai’s body was enrobed in not one or two, but twenty layers of fine silk, providing an initial shield against external elements. Silk, revered in ancient China, was not just a sign of luxury but also acted as an effective barrier to microbes that could cause decomposition.

Her body was then nested within four lacquered coffins, each one fitting snugly into the next. These coffins were drenched in a clear, slightly acidic liquid with high levels of magnesium, believed to have contributed to the preservation. On exposure to air, this liquid turned brown, hinting at the possible presence of oxidizable organic compounds.

Further, the coffins were sealed within an airtight tomb packed with charcoal and layered with several feet of clay on top. This meticulous sealing process ensured a dry, oxygen-depleted environment within the tomb. Combined with the insulating properties of charcoal and clay, it created a microenvironment devoid of the usual decomposition-catalyzing bacteria.

Interestingly, traces of mercury were also detected in Xin Zhui’s coffin. Historically, mercury was believed to have mystical properties that could ensure immortality, and its presence suggests it may have been employed as an antibacterial agent in this case.

The cumulative impact of these preservation techniques, each painstakingly designed and implemented, was profound. The synergy of the materials and the environmental control within the burial vault is primarily credited for the unprecedented level of preservation of Lady Dai. The tomb effectively acted as a time capsule, offering an unparalleled glimpse into the past.

Lifestyle and historical significance

From the exquisite artifacts unearthed from her tomb to the luxuriant meals she consumed, Xin Zhui led a life of opulence that speaks volumes about the grandeur of China’s nobility. As the wife of Li Cang, the Marquis of Dai, she was a figure of influence and prestige.

Upon excavation, Lady Dai’s tomb yielded an astonishing array of luxurious items. These artifacts ranged from richly embroidered silk garments and lacquered vessels to an impressive collection of musical instruments and cosmetic boxes. The diversity and quality of these artifacts were a testament to her affluence and high social standing.

Her innermost coffin even held prepared meals, signifying her penchant for gourmet food. This predilection extended to her lifetime, as evidence suggested that Xin Zhui frequently indulged in fine dining, possibly contributing to her obesity and numerous health conditions, including coronary heart disease and diabetes.

The wealth of artifacts discovered alongside Xin Zhui not only illuminated her extravagant lifestyle but also revealed the intricate details of the Han Dynasty’s aristocracy. These historical relics have proven invaluable in understanding the cultural and social nuances of this era. They have offered insights into the Han Dynasty’s dress codes, dietary habits, beauty standards, and artistic inclinations, adding depth to our knowledge of ancient China.

The mystery surrounding Lady Dai

Despite the numerous investigations and studies conducted on Lady Dai, her exceptionally preserved state remains shrouded in mystery. The seemingly miraculous condition of the mummy has baffled scientists for years. A mystery liquid found in her coffin, now believed to be a critical component in her preservation, has been a subject of conjecture and speculation among archaeologists and pathologists alike.

Scientists initially believed the liquid to be bodily fluids, but its preservation qualities have led some to theorize that it might have been a traditional Chinese herbal solution. Its slightly acidic nature and traces of magnesium, may have contributed to the body’s remarkable preservation, inhibiting bacterial growth.

This preservation theory is supported by the discovery of multiple coffins, which, when sealed together, created an almost airtight and watertight space. The tomb itself was further packed with charcoal and sealed with layers of clay, effectively creating a sterile environment that thwarted bacterial invasion. Yet, this theory has its skeptics. It doesn’t fully explain why Xin Zhui’s remains have resisted decomposition so impressively while other bodies buried in similar airtight and watertight environments have failed to do so. The bodies of her husband Li Cang and a younger man, possibly their son or Lady Dai’s brother, succumbed to the forces of time despite being buried in similar conditions.

This ongoing mystery surrounding the Lady Dai adds an intriguing dimension to her story, ensuring Xin Zhui’s mummy remains a subject of keen scientific interest and research.

Current condition and display

Although over two millennia have passed since Xin Zhui’s demise, her body has withstood the test of time remarkably well. That said, the passage of time has not been entirely benign. Since her discovery, exposure to oxygen has led to some degree of deterioration, particularly in the form of discoloration and drying of her skin. Nonetheless, she remains a marvel of preservation.

Today, the mummy of Lady Dai resides in the Hunan Provincial Museum in Changsha, China. The museum offers a unique opportunity to come face-to-face with a figure from the Han Dynasty, preserved in a near-life-like condition. Besides the mummy, the museum also houses a wealth of artifacts from her tomb. These objects range from exquisite silk garments and lacquer ware to traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions, all of which were interred with Xin Zhui to accompany her in the afterlife.

The intricacies and luxuries of Xin Zhui’s tomb have enabled a surprisingly detailed understanding of the Western Han Dynasty’s diet, agricultural practices, hunting methods, animal domestication, food production, recipe cultivation, and even the structure of one of the world’s most enduring cuisines.

Unraveling the threads of eternity

Lady Dai, with her immaculate preservation and fascinating lifestyle, is more than an archaeological marvel—she is a window to a bygone era.

Her tomb, laden with extravagant artifacts, provides an unparalleled glimpse into the luxurious lifestyle enjoyed by the Han Dynasty’s elite. Yet, her physical ailments underscore the inevitable consequences of indulgence and excesses, a sobering reminder that transcends time.

But the most enduring legacy of Xin Zhui lies in the mystery that shrouds her exceptional preservation. The details about the peculiar liquid within her coffin or the remarkable protection offered by her silk-swathed lacquer coffins continue to intrigue scientists and history enthusiasts alike. They serve as tantalizing puzzles, awaiting unraveling, bridging our quest for knowledge with the unparalleled wisdom of the ancients.

Xin Zhui, China’s Sleeping Beauty, is not just an emblem of the Han Dynasty’s splendor. She embodies our incessant quest to comprehend our past, our health, and our cultural heritage, making her one of history’s most valuable teachers.