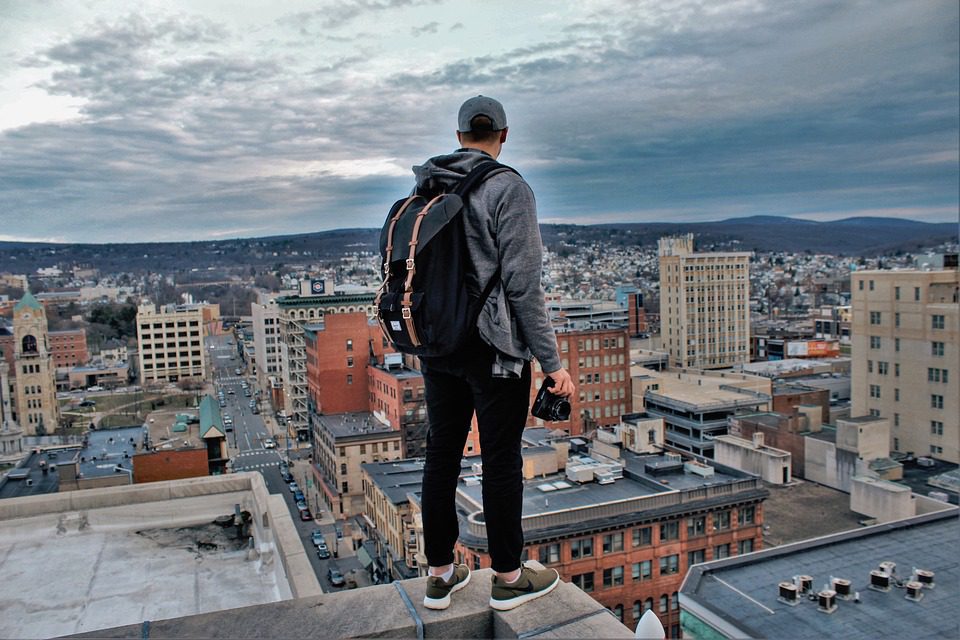

Have you ever visited a really high building or looked over the edge of a cliff or bridge and suddenly confronted an illogical but compelling urge to step forward? Not jump, necessarily, but step out into that vast empty space as though drawn there by some mysterious force. That urge is a real thing, which in French is known as l’appel du vide but translates into English as the more ominous-sounding call of the void.

High-place phenomenon

Scientists know this feeling as the high-place phenomenon and have found out a few important things in particular about this unnerving call:

- Only about 50% of us will experience it in our lifetime

- It can happen with both non-suicidal people as well as with people suffering from suicidal thoughts or suicide ideation, as psychologists call it

- That it results from some miscommunication of a basic human safety signal in our brains.

Why do non-suicidal people experience the call of the void? Psychologists suggest that one way to explain the phenomenon is that it works as a confirmation of the will to live. Think of it this way: you walk to the edge of the cliff and look over. You are overcome with this sudden urge to step forward to answer the Call. But you don’t step. Instead, you back away suddenly, shaken or even scared by the intensity of the feelings you just experienced. In those safe but shaky moments after, your brain tells you this: “You wanted to step forward but didn’t because you want to live more than you want to die.”

This theory is also known as the “vertigo of possibility,” which means that you feel great power and comfort in knowing that you can choose to answer the Call, but you don’t. Instead, you choose to step back, choose to live, and celebrate your life (when your heart rate finally gets back to normal).

A life-or-death game of blackjack

Another theory seems even more illogical. Cognitive neuroscientist Adam Anderson from Cornell University suggests that the Call is actually a defense mechanism based on a gambling analogy. Consider this scenario: you visit a casino and immediately begin to lose money at a blackjack table. You are so afraid of continuing to lose that you actually begin to gamble higher and higher stakes on each hand. The future loss of more and more money is not as immediate in your mind as the fear of losing the next hand, so you continue to up your bets exactly because you are afraid of ending the night as a loser.

The call of the void works the same way. You are naturally afraid of the threat posed by the edge of the cliff (as you should be), but your brain sends you a signal that the best way to overcome that immediate threat is to step into it, even if that means you plummet to near certain death. This explains, for instance, why someone with intense acrophobia (fear of heights) will leap off a mountain with a hang glider or climb extremely dangerous mountains.

High-level motion sickness

A third theory put forth by Carlos Coelho is much simpler: steep drops and high places in combination can create very similar symptoms to sea sickness. You think you are steady and balanced because your feet are firmly on the ground, but your eyes see visual cues that suggest that you are not safe at all as you look out over the city or valley below. These two systems collide in your brain, creating dizziness, a feeling of nausea, weakness in your knees, and a strong sense of disorientation. In a boat, your instincts signal you to sit down, while on the edge of the cliff, they tell you to step back so you can reset your sight on more stable visual cues.

Your fear keeps you safe from the call of the void

Regardless of which explanation makes the most sense to you, rest assured that your brain is managing this sudden Call in your best interest. As Coelho explains, having sudden fear when confronting the voice is the best of the two alternatives. “Lack of fear kills a lot of people,” he reminds us.