SOS is known, the world over, as a standard distress signal. But what does SOS stand for? Interestingly, it doesn’t actually mean anything.

The commonly held belief that SOS stands for Save Our Souls or Save Our Ship is untrue. These are bacronyms, that is, acronyms applied after the fact, and they have taken on popular value.

To understand how the term SOS came into common use, we have to go back in time and look at Morse code.

The beginnings of wireless communication

In the late 19th century, there was a lot of interest in the idea of wireless telegraphy—the concept of transmitting signals without wires. Guglielmo Marconi, a young Italian aristocrat with an interest in science, was one of the most prominent researchers in this field.

A series of private tutors educated Marconi at home. He never formally attended any college of higher education. That didn’t stop him from experimenting with radio waves as a basis for a wireless telegraphy system.

The butler did it

Twenty years old, and with a thirst for knowledge, Marconi began building his own equipment and conducting experiments. An interesting factoid that gets less attention than Marconi himself is that his butler, a man called Mignani, helped to build the first wireless machines.

After some initial success, Marconi had a working device that could send and send messages for up to 2 miles. But, he needed funding and support to continue his work. With little encouragement from the Italian government, Marconi moved to London. After a series of ever-greater demonstrations, the first wireless transmission systems were born.

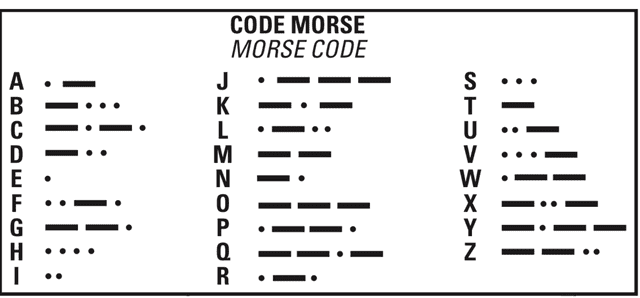

People used these machines to send messages using a system of dots and dashes to represent individual letters. This was known as Morse code.

Early distress signals

Shipping became one of the early adopters of Marconi’s wireless system. Suddenly, and for the first time, vessels at sea could stay in contact with the land and each other, even when out of sight.

By the early 20th century, many vessels had wireless communication. It quickly became apparent that a universal distress call was necessary. The UK used a call sign of CQ for land-based, wired communications to identify a general message. The Marconi company suggested a signal of CQD as the general distress call for wireless operators.

International confusion

At the same time, Germany had begun to adopt a Morse code sequence of three dots followed by three dashes followed by three dots as their distress code. Other nations and navies were using different call signs for their distress signals. This caused confusion on the high seas when different national vessels sent out calls for help.

At an international radiotelegraph convention held in Berlin in 1906, the world adopted the German Morse code sequence as the standard global distress signal. The adopted international regulations described a series of dots and dashes without reference to the alphabet. So, they did not officially call the original distress signal by the letters SOS.

SOS in its infancy

Since the international Morse code representation of the letter S was three dots and the letter O three dashes, it wasn’t long before the distress signal became known as SOS. History records that the first real SOS calls were sent in 1909.

As with all things, it took a few years for previous practices to die out. During the Titanic disaster of 1912, telegraph operators used both the CQD and SOS distress signals. The initial confusion this caused may have been the deciding factor in the final phasing out of the CQD sign.

The Titanic, and in particular, the part that wireless transmissions played in saving lives led to greater public recognition of Marconi and his invention.

SOS through the ages

SOS soon became the universal cry for help. People use it for more than simple wireless signals. Many stranded people have signaled for help with an SOS distress signal written in the sand, the snow, or with rocks. This has led to their rescue.

SOS is a palindrome and an ambigram. Meaning it is a word that reads the same both forward and backward and the right way up or upside down—a great help for spotters from the air looking down. This may have helped with the adoption of the SOS distress signal.

Developments in the use of distress messaging continued throughout the twentieth century. First, there were variations in the original SOS to specify the type of accident or emergency. Later, MAYDAY was added as a voice code signal.

During World War Two, additional suffixes were added to the SOS distress call to communicate the type of attacking vessel. So, if under attack by a submarine, the code SOS would have the following signal SSS, or an operator might use SOS RRR for a surface attack.

Automation

An early flaw with the distress signal was the reliance on the presence of radio operators at the telegraph machine when an SOS message was sent. If a distress signal was sent and the radio personnel were at lunch or asleep, no one would hear it.

Later versions of the telegraph machine included an automatic alarm that would sound to signal the receipt of an SOS message. Thus ensuring that someone would hear the SOS when the staff were not at their stations.

The alternative SOS

Interestingly, another well-known SOS doesn’t actually refer to the distress signal at all. The SOS in the name of the charity SOS Villages refers to the original name of the organization. Before it was known as SOS Villages, the charity was a social club called Societas Socialis, designed to raise funds for children in Austria. And so, in this case, the SOS is actually an acronym.

Today, an SOS village is present in almost every country around the world.

The modern SOS

With the advent of modern communications equipment, the SOS signal has been in decline. These days, a single press of a button will broadcast a vessel’s emergency instantaneously to satellites orbiting overhead, and emergency services will immediately know the vessel’s exact position, even if they are in the middle of nowhere.

But it’s unlikely the good old SOS will die out completely as long as someone uses it as a visual distress signal in pebbles on the beach of a deserted island. Or sings ABBA covers.

It’s always good to have an analog backup.