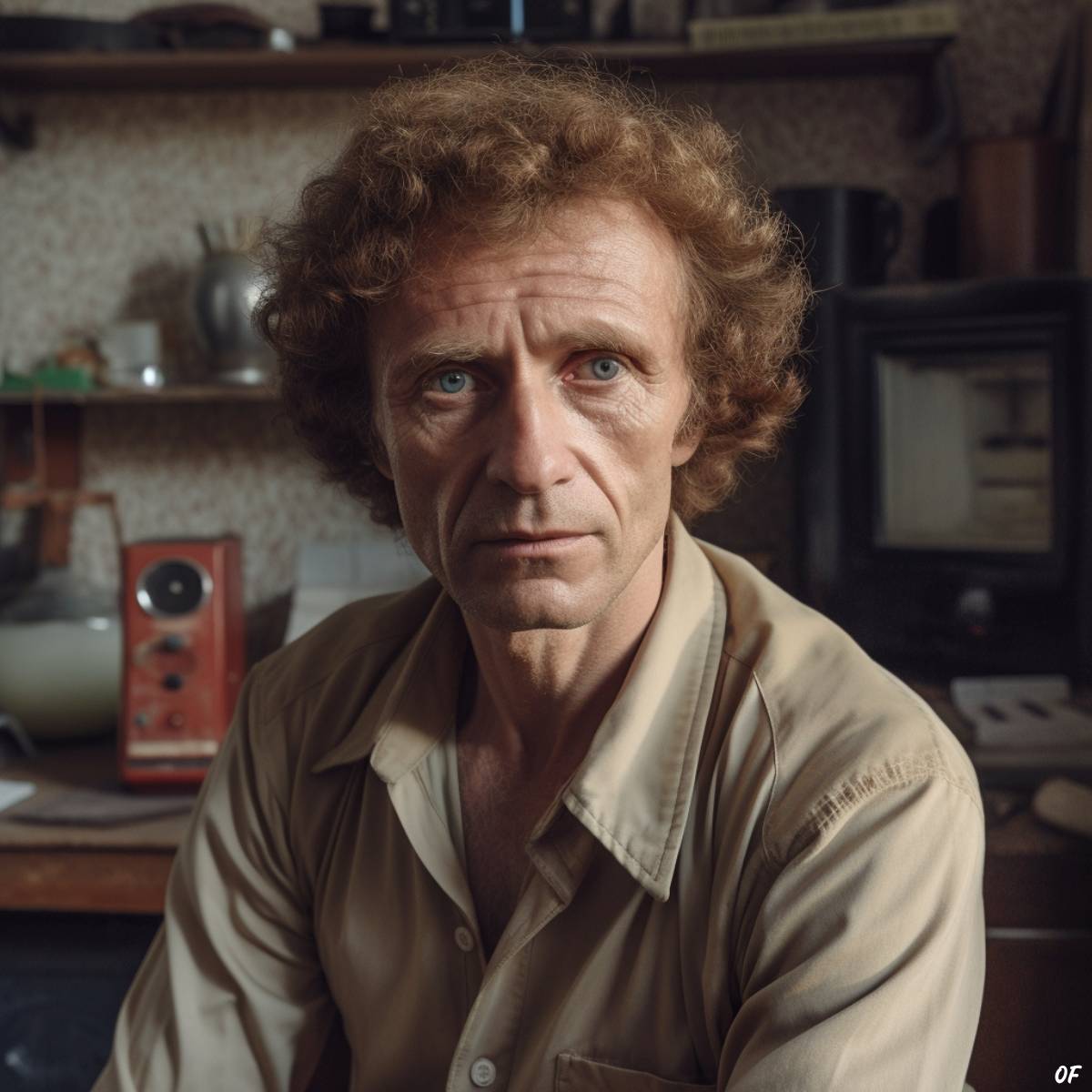

In the annals of history, certain names stand out for their associations with major world events. Among these, Viktor Bryukhanov is a name forever entwined with one of the greatest peacetime nuclear disasters in human history. As the first and only director of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, Bryukhanov oversaw the construction and operation of a facility that would later become synonymous with catastrophe.

This pivotal figure in the nuclear age passed away at the age of 85. His passing, announced by the plant’s press service, marks the end of an era and invites us to revisit the Chernobyl disaster and the role Bryukhanov played in it. As we delve into his life and legacy, we retrace the steps that led to the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, an event that changed Bryukhanov’s life and the lives of thousands across the globe. This man, who once presided over the promise of nuclear energy, ultimately faced the devastating consequences of its uncontrolled power.

The early life and career of Viktor Bryukhanov

Born on December 1, 1935, in Tashkent, Soviet Uzbekistan, Viktor Petrovich Bryukhanov began his journey into the world of energy at the Tashkent Polytechnic Institute. He emerged with an electrical engineering degree and an unwavering dedication to his country’s ambitious energy policies. Soon after graduation, Bryukhanov began working at Uzbekistan’s thermal power plant, where he acquired hands-on experience in the sector that would later define his life.

In 1966, Bryukhanov relocated to Ukraine, another republic within the sprawling USSR, and took a significant step toward his eventual role at Chernobyl. He joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that same year, aligning himself with the political force driving the Soviet Union’s scientific and technological advancements.

Bryukhanov’s talent and ambition were evident early on. By 1970, he had ascended to the role of deputy chief engineer at the Slavyanskaya thermal power plant, gaining valuable managerial experience in the process. Unbeknownst to Bryukhanov at the time, his career trajectory would soon shift from conventional power generation to the forefront of nuclear energy, a path that would lead him to his role at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

The construction and operation of Chernobyl

In 1970, Bryukhanov was entrusted with an enormous undertaking: building a colossal new nuclear power plant and a whole new city to house its workers. This would be positioned approximately 81 miles north of Kiev, in a region that would soon be known across the globe: Chernobyl.

With unyielding pride, Bryukhanov spearheaded the construction of the VI Lenin Nuclear Power Station, known universally as the Chernobyl power plant. The construction process, completed in 14 years, featured four RBMK nuclear reactors, an operating system that the West had rejected due to concerns about design flaws. Nevertheless, under Bryukhanov’s leadership, the Chernobyl plant was up and running, producing electricity for 30 million homes and businesses across the Soviet Union.

Yet, the construction of the nuclear power plant was only half the task. Bryukhanov also oversaw the development of Pripyat, a stunning new city, or “atomgrad,” designed to support the power plant. From the ground up, he constructed a city adorned with 30,000 Baltic rose bushes and boasting a population of 50,000 by 1986. This feat of urban planning featured excellent schools, well-equipped sports facilities, and, by Soviet standards, supermarkets brimming with supplies.

However, the construction journey was far from smooth. Deadlines were missed, and material shortages led to compromising decisions that would later prove devastating. The government stipulated that the roof of the vast machine hall be constructed using a specific non-flammable material. When this proved unavailable, Bryukhanov opted to use highly flammable bitumen instead. Similarly, under mounting pressures to meet energy targets, he elected to overlook a radioactive leak that occurred in September 1982. These challenges and decisions, largely obscured at the time, would come to cast a long shadow over Bryukhanov’s legacy.

The 1986 Chernobyl disaster

In the early morning hours of April 26, 1986, an ominous specter arose from the heart of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant—the monstrous, invisible plume of a radioactive dust cloud. Unleashed by the catastrophic explosion at Reactor 4, this deadly dust cloud carried within it an assortment of radioactive isotopes, including iodine-131, caesium-137, and strontium-90. Invisible to the naked eye, but lethal in its potency, the cloud began its silent, insidious journey, borne by the winds. It drifted across borders, contaminating vast stretches of land in Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia, and even reaching as far as Western Europe. As the radioactive particles settled, they seeped into the soil, contaminated water supplies, and infiltrated the food chain, setting the stage for a slow-burning disaster that would claim lives and impact the environment for decades to come. This catastrophic amount of radioactive material contained a radiation level about 400 times that of the Hiroshima atomic bomb. The Chernobyl dust cloud wasn’t just a symbol of a singular nuclear catastrophe, but a chilling testament to the lasting and borderless consequences of nuclear disasters.

The initial response to the disaster was one of confusion and denial. Bryukhanov himself was one of the first officials on the scene and spent the following hours attempting to piece together what had occurred. Clouded by an unfathomable reality and faced with an unprecedented disaster, Bryukhanov’s initial response proved ill-judged.

Reports from the scene were drastically understated, leading to a perilous delay in the Soviet Union’s response. Bryukhanov, despite evidence to the contrary, insisted that reactor number three could continue operating. His initial report to Moscow estimated the radiation levels to be a mere 3.6 roentgen per hour, a reading that was capped by the available measuring devices. The actual level, as revealed later, was closer to 15,000 roentgen per hour, a fatal level of radiation.

Furthermore, Bryukhanov’s reluctance to evacuate Pripyat immediately after the disaster put tens of thousands of lives at risk. It was not until the following day, 36 hours after the explosion, that the evacuation order was given, by which time many residents had already been exposed to high levels of radiation.

This era marked a defining moment in Bryukhanov’s life, when the enormity of the situation combined with the insurmountable task of managing it led to a series of catastrophic decisions that would forever alter his life and the lives of countless others. His role during this calamity is an integral part of the Chernobyl narrative, a story of human error and institutional failure on a tragic scale.

The trial and imprisonment of Viktor Bryukhanov

Following the Chernobyl disaster, Bryukhanov’s fall was as precipitous as his rise. He was swiftly dismissed from his position as the director of the Chernobyl power plant. In the wake of the catastrophe, he found himself at the center of an investigation, charged with safety violations, gross negligence, and abuse of power. A culpability that many saw as a byproduct of the Soviet Union’s wider system of governance.

Bryukhanov’s trial in 1987 was as much a public spectacle as it was a judicial proceeding. Broadcast on Soviet television, it was an unprecedented moment of public reckoning. The former power plant director, along with several other officials, was held accountable for the world’s worst nuclear accident.

In a grimly symbolic verdict, Bryukhanov was sentenced to ten years in a penal colony in Donetsk, a region shadowed by the Chernobyl fallout. The image of a man who was once at the helm of one of the world’s most advanced nuclear facilities being led away to serve his sentence is indelible.

Throughout the trial, Bryukhanov maintained a stance that pointed to systemic failure rather than individual malfeasance. He consistently argued that the disaster was a result of a wider Soviet culture that prioritized speedy construction and operation over necessary safety measures. In 2006 Bryukhanov stated in a in Profil magazine interview after his release from prison, “The scientists, the construction engineers, the prosecution experts, they all defended their professional interests, and that was all. It was a tissue of lies that distracted us from the search for the real causes of the accident.” Bryukhanov held a conviction that there was a global concealment of nuclear transgressions, suggesting that this evasion of accountability wasn’t exclusive to his homeland. He contended, “(It’s) not just us: the Americans, the French, the English, the Japanese, are all hiding the real causes of accidents at their own nuclear power stations.”

While his indictment brought a sense of justice to a tragedy that claimed so many lives, it also underscored the complex interplay of individuals, institutions, and ideologies in the Chernobyl disaster narrative. The story of Bryukhanov’s trial and imprisonment is emblematic of the broader search for accountability in the aftermath of Chernobyl, a quest that continues to be explored and questioned even today.

Political fallout

The political fallout from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster echoed as profoundly as the radiological one. The Soviet Union, already on the precipice of systemic collapse, was ill-equipped to manage the catastrophe. The initial attempts at downplaying the disaster and subsequent reluctance to disclose the true extent of the damage sowed seeds of mistrust within the international community and sparked outrage among its own populace. The glasnost policy, introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev, meant greater transparency, but Chernobyl tested this principle to its limits. The eventual admittance of the government’s failings not only shone a glaring spotlight on the weaknesses of the Soviet system but also stoked the fires of independence movements within Ukraine and other Soviet states. This catastrophic event served as a catalyst for accelerating the dissolution of the Soviet Union and reshaping the geopolitical landscape of Eastern Europe, and, indeed, the world.

Post-prison life and legacy

Having served half his sentence, Bryukhanov walked free in 1991, stepping into a world forever changed by the event he was closely associated with. Ukraine was no longer part of the U.S.S.R., and the Chernobyl disaster was now an undeniable part of its history and identity. Bryukhanov relocated to Kiev, where he worked for Ukraine’s Economic Development and Trade Ministry, a role that, although important, was far removed from his former status.

In 2019, the HBO miniseries “Chernobyl” catapulted Bryukhanov back into the public eye, with British actor Con O’Neill portraying the former power plant director. The series sparked a renewed interest in the Chernobyl disaster and invited fresh scrutiny into Bryukhanov’s role and responsibility. The dramatization, while serving to preserve the memory of the disaster, also opened debates about the simplification and sometimes sensationalization of historical events.

Bryukhanov’s legacy remains entangled with the enduring impacts of the Chernobyl disaster. On the one hand, his name is intrinsically linked to an event that caused tremendous human suffering and environmental destruction. On the other hand, his narrative underscores the complexities of working within an ideologically driven system that arguably prioritized advancement over safety regulations.

The final act

Viktor Bryukhanov, who passed away in a hospital in Kiev, is survived by his wife, Valentina, their two children, and several grandchildren. Despite the public controversy surrounding Bryukhanov’s professional life, he was remembered by his family as a caring husband, a dedicated father, and a doting grandfather. It serves as a stark reminder that beyond the headlines and historical narratives, the protagonist of this story was also a man with personal commitments and private joys.

Reflecting on Bryukhanov’s legacy invites us to explore the intricate, multifaceted relationship between an individual and the history he was part of. He was an architect of atomic energy, a man who both symbolized and served an ambitious yet flawed Soviet system. His life was inexorably marked by one of the most catastrophic nuclear accidents ever recorded—the Chernobyl reactor explosion. His actions and decisions, both before and after that fateful night in 1986, played a significant role in shaping not only the course of his life but also the lives of countless others and the environment itself.

His death, in essence, marks the end of a significant chapter in the narrative of nuclear power. It also highlights the enduring relevance of the Chernobyl disaster, which continues to inform our approach to nuclear safety and our understanding of its environmental impact, over three decades later. As we delve into the life of Viktor Bryukhanov, we find ourselves reflecting on our own relationship with nuclear power, our respect for nature, and our responsibility towards it. This contemplation, perhaps, is one of the most significant aspects of his complex legacy.

In the end, Bryukhanov’s life is a testament to the age-old adage that power, whether atomic or administrative, comes with immense responsibility. His life and the disaster he is associated with will continue to be a significant part of the discourse surrounding nuclear energy, serving as a cautionary tale for generations to come.