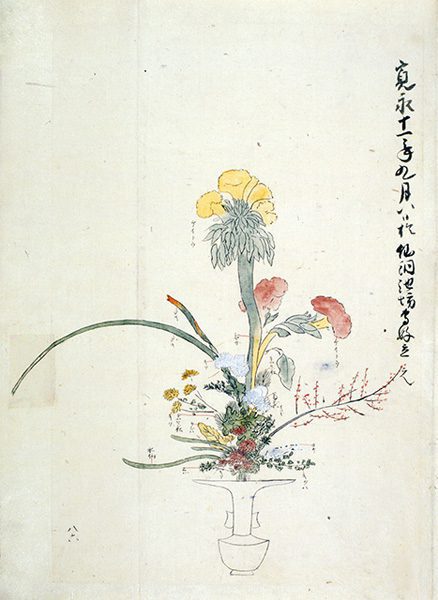

The Ikebana flower arranging technique is a refined Japanese art.

Established during the Heian period (784 – 1185 AD), the art form has deep roots in Japanese culture. It has played a central role in Japanese Tea Ceremonies. Ikebana requires advanced skills. Still, Japanese people consider Ikebana the most elegant way to decorate one’s home.

The Japanese art of flower arranging has developed over the centuries. Ikebana combines aesthetics with symbology and meaning. Each flower is carefully selected for its significance and beautifully crafted to shape.

Ikebana differs from arrangements in Western culture which values appearance alone. One of the most ancient Japanese art forms, Ikebana, follows a strict set of rules based on Buddhist expression.

A brief history Of Ikebana

Ikebana has its roots in 6th-century Japan as a formalized floral offering to Buddha. Buddhist missionaries led by Ono no Imoko, a former envoy turned Buddhist monk, founded the first school of Ikebana.

Ono no Imoko was a tea master. The Buddhist tea ceremony evokes all five senses, and flowers were central to the ritual.

Ono no Imoko established the basic principles of the Ikebana during his residence at The Rokkakudo Temple in modern-day Kyoto. The arrangements boasted a perfect balance of vision and emotion.

A growing appreciation of the art resulted in the establishment of schools across Japan.

The practice flourished across the centuries and branched off into several different styles. Each has its own distinctive character and meaning. The art form gradually made its way into private homes. Here pre-built takocoma alcoves displayed the arrangements.

What is the purpose of Ikebana?

In Buddhism, Ikebana is more than just a flower arrangement; it is a form of worship. The purpose is not just to appreciate the beauty of flowers but to find meaning in the simple things in life.

Ikebana arrangements are symbolic. They stimulate emotions or mark life events or important days of the year. The position of the branches is always symbolic or metaphorical.

Artists shape and position branches to represent celestial principles, such as the earth, moon, and sun. Some schools use the rule of three to represent the heavens, the earth, and the human spirit.

Symbolism and meaning

The symbolism and meaning incorporated into Ikebana vary between Japanese subcultures and traditions.

Almost always minimalistic, each flower has its own meaning based on its color, appearance, or growth patterns.

Cherry Blossom is a popular symbol in Japan. It represents acceptance of imperfections and compassion. The Lotus brings harmony to the space and heightens spiritual awareness. Whilst the Peony instills confidence and good fortune upon those who view it.

Symbolism and the seasons lie at the core of any Ikebana structure, supported by bamboo grass used all year round.

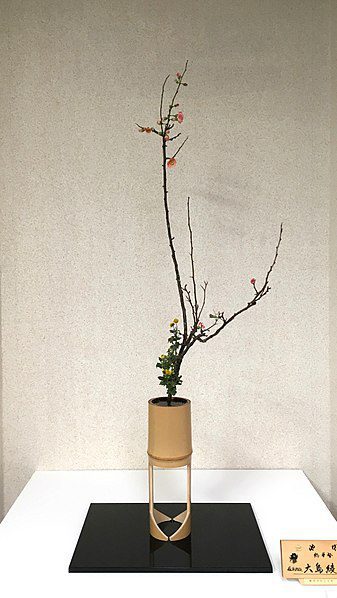

Japanese plum branches form a common feature for New Year’s arrangements. Japanese Iris takes center stage in the summer. Chrysanthemum takes prominence in autumn.

More than just an arrangement, Ikebana is a manifestation of culture. The art form transcends aesthetic pleasure and aims to enhance the qualities of the flowers and empower the space that they occupy.

What are the basic features of Ikebana?

The name Ikebana means ‘to make flowers alive.’ The art form takes one of two styles, moribana (short vase) and nageire (tall vase).

Yet, major schools around the world teach three core techniques. Each has its own character and rules, but the basic concept is to use native flowers to idealize nature.

Rikka style

Rikka, one of the earliest of the Ikebana styles, was developed to emulate paradise and bring calm and serenity into the space.

Ornate Rikka arrangements reflect the energy of the cosmos. The nine structural concepts of the Rikka style represent the natural landscape. It amplifies beauty with its simplicity.

Rikka has been in decline in recent years, giving way to later styles. Still, a highly respected type of Ikebana, Rikka forms the cornerstone of the art form.

Seika style

A later Ikebana style, Seika allows for free expression. Those who founded the strict rules of Rikka developed Seika to introduce more fluidity into the arrangements.

Seika belongs to the Nageire family of flower arranging, which means ‘to throw in.’ Yet, Seika is far from a random and thoughtless technique. Associated with Zen, Seika attempts to weave one’s individuality within the fabric of the natural universe.

Seika has only three core positions that the artist must adhere to, Shin, Soe, and Uke. Combined, they create a triangle – the most powerful shape in nature. Traditionally sculpted from a single plant, modern schools allow for the incorporation of two or three plants.

Moribana style

Moribana is the modern method of Ikebana. During the early years of the art, Ikebana adorned top Buddist alters and takocoma alcoves. Yet, today, Ikebana masters prefer viewing the flowers from all sides.

Moribana arrangements introduce complexity, allowing for a 360-degree view of the arrangement.

Moribana translates as ‘piled up flowers.’ This method allows for the sculpture of more than one plant to create a striking 3-dimensional effect.

Moribana is more accessible to the viewer, allowing for a view of the plants from any part of the room.

Jushi

A fourth style called Jushi incorporates flowers and blossoms not traditionally used in the other styles.

This branch of Ikebana allows for freestyle expression. In this form of art, artists can add unusual flowers to the decoration, but only in odd numbers.

What are the rules of Ikebana?

In the School of Ikebana, lines, form, and coordination of color are very important. No matter what style the practitioner chooses to follow, they must adhere to the basic concepts.

Ikebana is an artistic expression that allows human creativity to experiment with natural lines. Practitioners cut flowers into unrecognizable shapes. Leaves and stems are beautifully sculpted to complement the branches. These are often arranged in sets of three or nine.

Ikebana is more like a sculpture than an arrangement. The result varies in size and composition, but common elements are present throughout. The arrangement should have stems thick enough so the flowers stand upright without support. The arrangement can include a single flower or several.

Contemporary Ikebana

Ikebana has experienced a revival in recent years as more people seek to personalize decor and adopt traditional Japanese styles. These standing flowers make a superb addition to any environment. The growing interest has seen the establishment of many Ikebana schools in recent years.

The Ikenobo school, the oldest school in Kyoto, still survives. It serves as an inspiration to newer traditional schools established during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Ohara school branched off from the Ikenobo school and created the Moribana style. The Sogetsu school teaches the basic principles of Ikebana with modern materials like steel, and plastic.

Overall, there are thousands of Ikebana schools in Japan and across the globe. All are dedicated to preserving the art of flower arranging.

From Buddhist altars to home decoration, this unique and powerful style has not lost momentum. As new and innovative sculptors adopt the art, they drive it in new directions.

Ikebana is more than just a hobby. It preserves Japanese culture and symbolism. It is all encapsulated in a beautifully crafted and personalized ornament.