At least since the days of ancient Rome, Western Europeans have been utilizing a method called pollarding to regulate the growth and shape of trees. But in medieval East Asia—and prepare your plosives now!—this primarily pragmatic pruning practice was elevated to a state of poetic perfection.

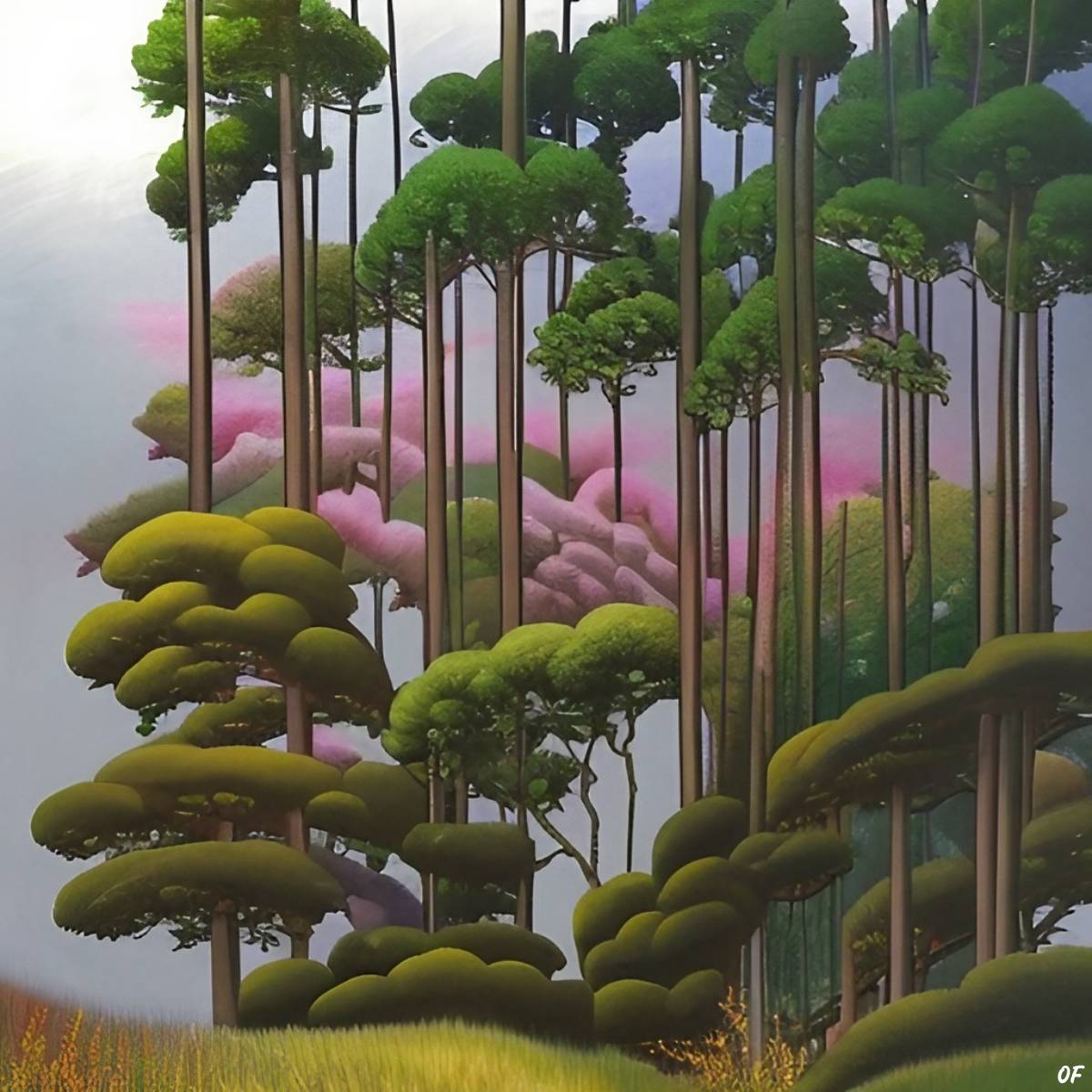

Meet daisugi, the awe-inspiring and ancient Japanese technique of woodland management that transforms slender cedar saplings into a breathtaking forest of “platform” trees, transcending the limits of pollarding and resulting in beautiful, knot-free lumber—an integral part of traditional Japanese architecture.

All but abandoned, daisugi has recently enjoyed a revival in popularity as a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to clear-cutting forests. With its unique blend of artistry and forestry techniques, daisugi offers a powerful reminder of the ingenuity and resourcefulness of ancient cultures, and maybe even a promising glimpse into the future of sustainable forestry.

Propertius, pollarding, and the Portico of Pompey

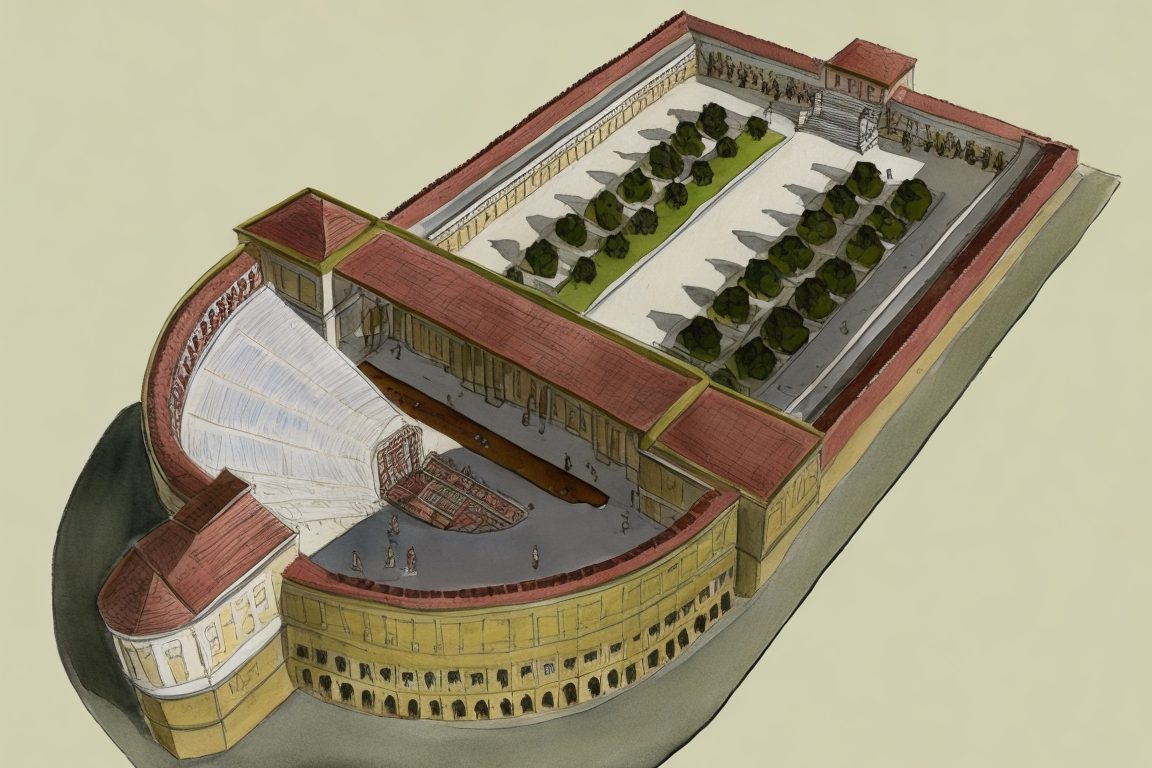

It’s somewhat difficult to know whether a woman named Cynthia really lived in 1st-century Rome, but her name—or at least, pseudonym—certainly lives on in the poetry of Sextus Propertius, one of the leading voices in the Augustan age of Latin literature. An elusive beauty or a poetic convention, Cynthia was the subject of many of Propertius’ 92 elegies, a genre of highly stylized Roman poetry that focused on love, loss, and the beauty of life. What does it all have to do with daisugi?

Well, in one of these elegies—32nd in his second book—Propertius scolds the unknowing Cynthia for not spending more time around his neighborhood, so that he could at least see her more often, even if from afar. “Forsooth,” he laments, “thou carest naught for Pompey’s colonnade, with its shady columns, bright-hung with gold-embroidered curtains; and you care even less for the avenue thick-planted with plane-trees rising in trim rows!”

These “rising rows of evenly planted plane-trees”—as another translation puts it—are one of the earliest known references to a form of tree pruning similar to daisugi, and now commonly known as pollarding. Although Propertius’ verse demonstrates that this practice was already widespread in ancient Rome, it wasn’t until the Middle Ages that (alongside a similar horticultural practice called coppicing) it became a ubiquitous method for encouraging consistent regrowth of trees to secure a constant supply of wood, particularly for fuel.

So unlike in the case of Pompey’s Portico—where the trees were pruned for aesthetic purposes—the trees of medieval Europe were shaped for practical reasons, resulting in a utilitarian approach to tree management. Daisugi began quite similarly; the results, however, were rather different.

Dulce et utile: the origins of daisugi

Famous but atypical, daisugi originated sometime in the early 15th century, during the Muromachi period (1333-1573)—or, more precisely, the Ōei era (1394-1427)—when the demand for high-quality lumber for the erection of temples, shrines, and other traditional buildings was at its peak.

At this time, Kyoto was the cultural center of Japan, and the city was home to many of the country’s most important political, religious, and cultural institutions. The construction of these buildings required large amounts of lumber, which was in short supply due to the limited availability of space and suitable trees.

In response to this challenge, in the nearby forests of Kitayama, Kyoto foresters developed the technique of daisugi, which allowed them to grow trees atop other trees, in a way that made possible the sustainable production of knot-free, straight lumber.

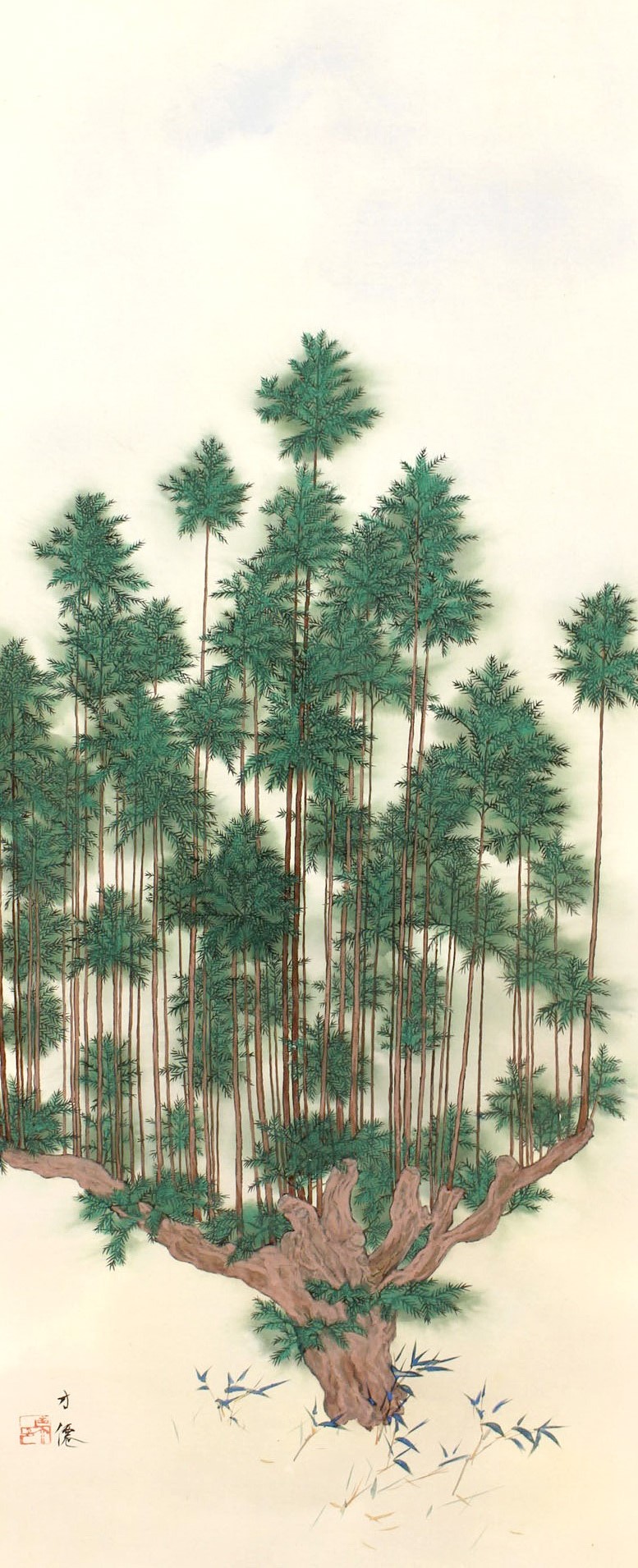

Well, it’s not exactly trees that we have in mind here, but one particular tree, endemic to Japan and selectively grown in Kitayama for centuries—the daisugi cedar.

The Kitayama cedar, the original daisugi tree

Cryptomeria is a unique genus of conifer that belongs to the cypress family and comprises only one species, indicatively termed Cryptomeria japonica. The English names for this tree include “Japanese cedar” or “Japanese redwood.” In Japan, however, it is known simply as sugi.

This is where the name of daisugi comes from. An easily decipherable compound, it is written as 台杉, combining the 台 kanji (“a pedestal,” “a stand”) with the Japanese character for cryptomeria (杉). Hence, daisugi, in literal translation, means “a pedestal sugi,” or even better, “a platform cedar.“

That is, indeed, a great description of the final result of this pruning method which—to quote Spoon and Tamago’s Johnny Waldman—resembles “an open palm with multiple trees growing out of it, perfectly vertical.” But how is it achieved, exactly?

The practice of daisugi, in brief

The practice of daisugi is a highly specialized and skilled craft that requires a deep understanding of the biology and growth patterns of trees. The process begins with the selection of a single tree, a Kitayama sugi, chosen for its straight trunk and vigorous growth. The tree is then pruned to remove all of the side branches, leaving only a cluster of new shoots at the top of the trunk.

Over the next few years, these shoots are carefully monitored and trained to grow vertically, using a system of bamboo poles and ropes. As the shoots grow, they are periodically—every couple of years or so—pruned and shaped to maintain a uniform size and shape. Eventually, the shoots develop into long, straight poles that are harvested for lumber.

With a harvest cycle of 20 years, the platform cedar yields a plentiful supply of wood from a single tree, which can survive for hundreds of years at the base. Moreover, the finished logs (generically referred to as kitayama maruta) are uniquely striated, slender, and knot-free, and so are highly prized for their unearthly beauty.

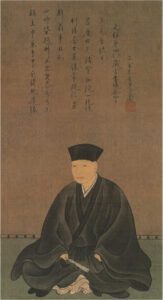

All credit goes to a man named Sen no Rikyū, Kyoto’s preeminent tea master in history, who first recognized the potential of Kitayama sugi as a building material and incorporated it into the Colored Shoin, sometime during the late 16th century.

Sukiya-zukuri and the canonization of (dai)sugi

In 1587, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a powerful Japanese samurai and daimyō (feudal ruler), enlisted the expertise of Sen no Rikyū, to guide him on aesthetic matters.

As part of this collaboration, Rikyū designed the Colored Shoin, an elegant building with eighteen tatami mats, located within Hideyoshi’s grand Jurakudai castle in Kyoto. This structure—now destroyed—is widely considered the first example of the sukiya-zukuri architectural style, which has since become a hallmark of Japanese design.

Characterized by the use of natural materials, particularly wood, sukiya-zukuri emphasizes simplicity, rusticity, and the incorporation of the surrounding natural environment. At its essence, it embodies a design philosophy of refined taste and appreciation for elegance, and is closely associated with cha-no-yu, the Japanese tea ceremony.

Now, the specific demands stipulated by Sen no Rikyū for the interior design of sukiya-zukuri tea rooms required the use of high-quality, straight-grained, knot-free lumber. The cedar trees from the Kitayama forests were uniquely suited to this task. That’s how they became such an important part of Japanese culture.

And that’s why daisugi had to be invented. Namely, as demand for kitayama maruta outstripped supply, the daisugi technique emerged as a way to increase forest output, marking a shift from exploitative to regenerative forestry. Developments such as this made Japan one of the earliest societies to undertake this transition.

The benefits of daisugi

Daisugi provides a host of advantages over traditional forestry methods that rely on the mass harvesting of existing trees and subsequent planting of new ones.

One of its main advantages is its ability to reduce the need to harvest wood from multiple trees. With daisugi, just one tree can produce enough lumber for a few traditional wood roofs, thereby reducing the environmental impact of logging.

Furthermore, daisugi aligns well with the principles of environmental conservation, as only the upper branches are harvested, leaving the rest of the tree undisturbed. This ensures the entire tree can continue to absorb carbon and other greenhouse gases from the atmosphere while providing habitats for local wildlife.

Last but not least, the lumber produced through daisugi techniques possesses exceptional qualities. It supposedly boasts 140% more flexibility than standard cedar and is 200% more dense and robust. Such superior quality wood is ideal for rafters and roof timber that require slender yet typhoon-resistant lumber, making it a popular choice for traditional Japanese architecture, even today, 600 years after the technique was first developed.

Preserving the daisugi technique

Despite the many benefits of daisugi, the practice is facing many challenges. One of the biggest obstacles—as Tom Eagar and Rachel Jonas pinpoint in a 2018 Boat magazine article—is the need to modernize old methods to fulfill new requirements. Although renowned for its durability, the Kitayama sugi is still a softwood and not ideal for use in load-bearing construction.

Additionally, Kitayama forestry necessitates extensive labor and time compared to regular forestry practices, and given the current economic climate, there are more cost-effective alternatives. Although researchers are attempting to discover methods to toughen the kitayama maruta for practical purposes, no substantial progress has been made yet.

The future prospects for Kitayama foresters appear gloomy. “There is hope, though,” claim Eager and Jonas. “If they can adapt kitayama maruta’s properties to suit the modern demands that are required of it, then it could be the beginning of something truly special; a sustainable timber for the future that bears the fingerprints of the past.”