Famously ambiguous and notoriously capricious, Baba Yaga is inarguably the best known of all legendary creatures in Slavic folklore. An old crone, a scary witch, a fierce protector, a wise teacher of mysteries, a bringer of death, a giver of life, a shape-shifter, a child-eater, a guardian of treasures—Baba Yaga is all of these, and more.

In most tales, she is described as a terrifying ogress who flies around in a mortar and wields a pestle; in others, however, she is depicted as a wise woman who helps lost travelers on their journey; yet in a third set of stories, she is actually they, as there are fairy tales which feature three baba yagas, usually sisters or cousins, all of them endued with magical powers.

An enigmatic and memorable character, Baba Yaga reveals a complexity that has captivated the imagination of storytellers, artists, and audiences for hundreds of years. To better understand her, it is necessary to first take a look at her origins and her triunity, as well as the etymology of her seemingly jocular name.

Baba Yaga’s complex origins

“Baba Yaga’s origins are not all that clear,” writes curtly but accurately former Yugoslav writer and Russian literature specialist Dubravka Ugrešić near the end of her resourcefully inventive 2010 postmodern novel Baba Yaga Laid an Egg. She then lists several theories regarding Baba Yaga’s folkloric parentage, none of which can be categorically proven, but all of which are unmistakably plausible:

One theory has it that she was the Great Goddess, the Earth Mother herself. Another, that she was the great Slavic goddess of death (Yaga zmeya bura); a third, that she was the mistress of all the birds; a fourth theory has it that she was a rival of the Slavic goddess Mokosh, and that she evolved over time from a great goddess into an androgyne, then into the goddess of birds and snakes, and then into an anthropomorphic being, until she finally acquired female attributes.

Indeed, Baba Yaga appears in many different guises across divergent fairy tales and Slavic cultures, and as a result she has come to encompass more than just one sphere of influence. As Małgorzata Oleszkiewicz-Peralba observes in Fierce Feminine Divinities of Eurasia and Latin America, “She is simultaneously connected to the heavens, the earth, and the underworld, as well as to the past, the present, and the future, to life and to death.” One would have to try hard to find a more complex character than her in European folklore, with as complex roots—and not just among witches. It is no surprise that she has become so iconic and enduring.

Baba Yaga, the Triple Goddess of yesteryear

As renowned American scholar and folklorist Jack Zipes remarks in the foreword to Baba Yaga: The Wild Witch of the East in Russian Fairy Tales, Baba Yaga transcends all definitions, not the least because she is “an amalgamation of powerful past deities—mixed with a dose of sorcery.” Once the Great Triple Goddess herself—downgraded to witch status by Christian demonization and folkloric simplification—this enigmatic figure remains one of the most potent and tantalizing figures in the Slavic imagination. In fact, she is perhaps still best described as triune rather than dualistic, as she seems to represent not just good and evil, or life and death—but also everything in between.

In his Encyclopedia of Russian & Slavic Myth and Legend, prolific mythologist Mike Dixon-Kennedy suggests that each of Baba Yaga’s three aspects can be equated to the three Fates of classical Greece. Writes he:

In her first aspect, as a fertility goddess, Baba Yaga is benevolent, bringing new life into the world. In her second aspect she maps out the course of human life and is both benevolent and malevolent. In her third aspect she determines the date of human death, the role in which she is most commonly regarded. In her triune state, Baba Yaga hovers over the birth of every new life, immediately threatening to take it back again. She has the power to send life into the earth and to recall it. She is the most terrible of all the regenerative fertility deities, encompassing life from conception through birth to death—and beyond.

From Baba Yaga to baba yagas

Hypothesized by mythologists for decades and recently popularized by neopagan weddings, the Triple Goddess is commonly portrayed in the form of a maiden, mother, and crone. The maiden, or virgin, is associated with youth and innocence: she is often seen as a symbol of new beginnings and potential. The mother represents nurturing, fertility, and abundance: she is the embodiment of love and protection. The crone, finally, is seen as a wise elder, associated with death and transformation: she is a reminder of life’s cycle and the importance of looking to the future.

Together, these three aspects of the Triple Goddess represent the eternal cycle of life, death, and rebirth. In Baba Yaga, they seem to find their consummate form, embodying the power of the feminine in all of its aspects. Baba Yaga is both the maiden, responsible for providing the heroes of Russian folklore with helpful advice and guidance, and the crone, who dishes out harsh punishments to anyone who fails to respect her power. She is also the mother, the one who protects her children and the world from forces that are beyond them, be they evil or merely eviler.

Interestingly, Baba Yaga’s triunity is made manifest in certain Russian tales, such as that of “The Bold Knight, the Apples of Youth, and the Water of Life.” In it, there appears not one but three baba yagas, each one older than the last, each one serving as a way station for our hero on his quest. In many ways, it’s more accurate to speak of “a Baba Yaga” rather than of “Baba Yaga”—in Russian, the name is never capitalized. Indeed, as Sibelan Forrester notes, Baba Yaga is “not a name at all, but a description, meaning ‘old lady yaga’ or perhaps ‘scary old woman.’” Although, to be fair, it’s not that simple.

Baba Yaga’s compound name

Baba Yaga’s name has seemingly innumerable variants and variant spellings across different Slavic languages, including Baba Yoga, Baba Roga, Baba Jaga, Yagabova, Egabova, Jagababa, Ježibaba, Jedibaba, Jedubaba, Indži-baba, Igaya, Yaganishna, Yagivovna, and so on. In most cases, however, it is a compound name, comprising two elements with independent meanings.

The first half of Baba Yaga’s name is the Slavic babble word for “grandmother,” akin to the English “granny.” In most Slavic languages, however, the word baba has a more general meaning as well, “an old woman,” and Baba Yaga is certainly always presented as a wizened, magical crone. In fact, one can argue—with Helen Pilinovsky—that “crone” is perhaps the best translation for baba in this context.

It is the second part of Baba Yaga’s name—yaga—that is far more difficult to decipher. In Gale’s Encyclopedia of Religion, Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas claims prehistoric origins for the word, deriving it from the Proto-Slavic *(y)ega, which means “disease,” “fright,” or “wrath” in Old Russian, Serbo-Croatian, and Slovene, respectively, and is related to the Lithuanian verb engti (“strangle, press, torture”). She goes on to say that the earliest form of this word may be further related to the Proto-Samoyed *nga, meaning “god,” or “god/goddess of death.”

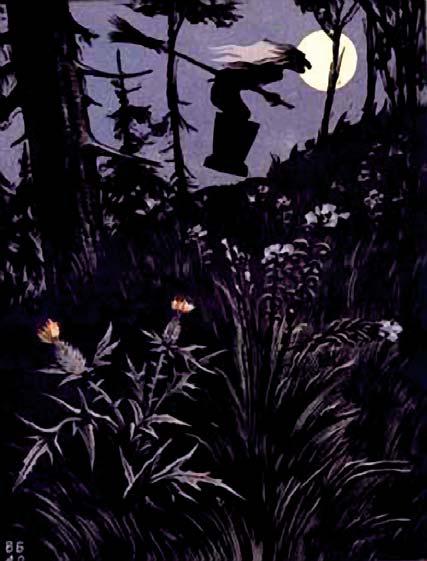

Either way, the second part of Baba Yaga’s name is likely intended to evoke a sense of dread and fear, reminding us of her sinister and dangerous reputation. Her appearance and demeanor—from her unsettling, skeletal form and her wild, unkempt hair, to her magic powers and her supernatural flying mortar—makes it clear why this would be the case.

The appearance of Baba Yaga

By his own admission, Jack Zipes knows of “no other witch/wise woman character in European folklore who is so amply described and given such unusual paraphernalia as Baba Yaga.” Not only that, but this elusive Slavic witch “shows very few characteristics and tendencies of western witches, who were demonized by the Christian church, and who often tend to be beautiful and seductive, cruel and vicious.” Well, Baba Yaga is none of that—and so much more.

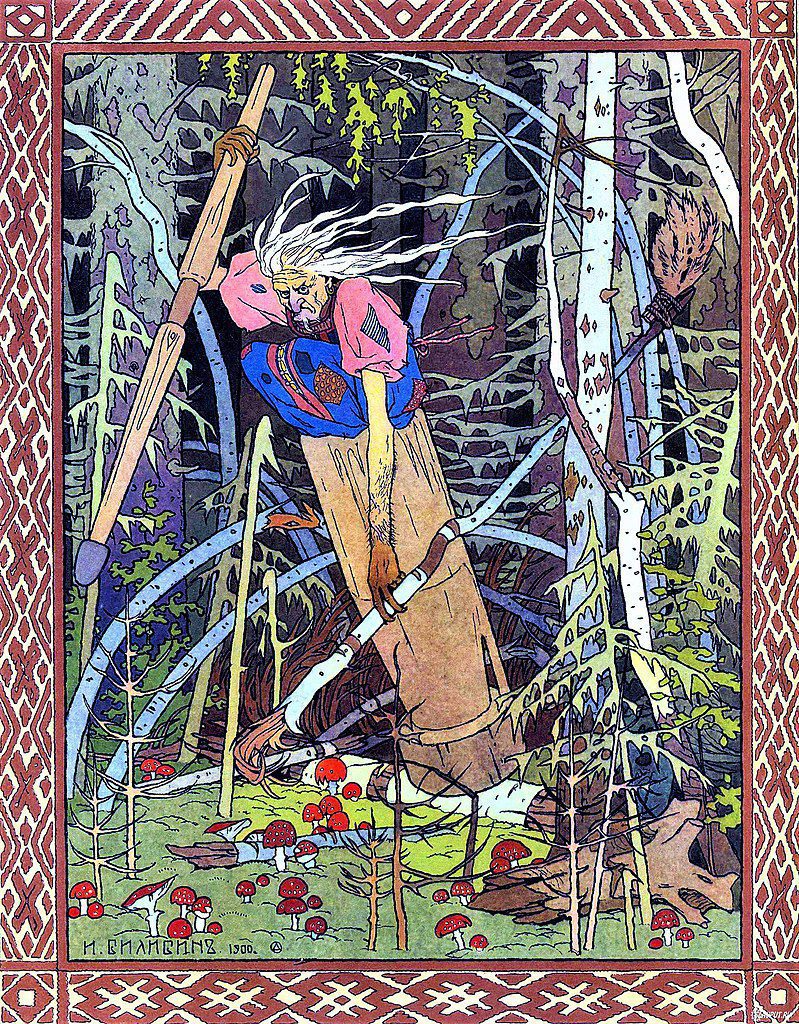

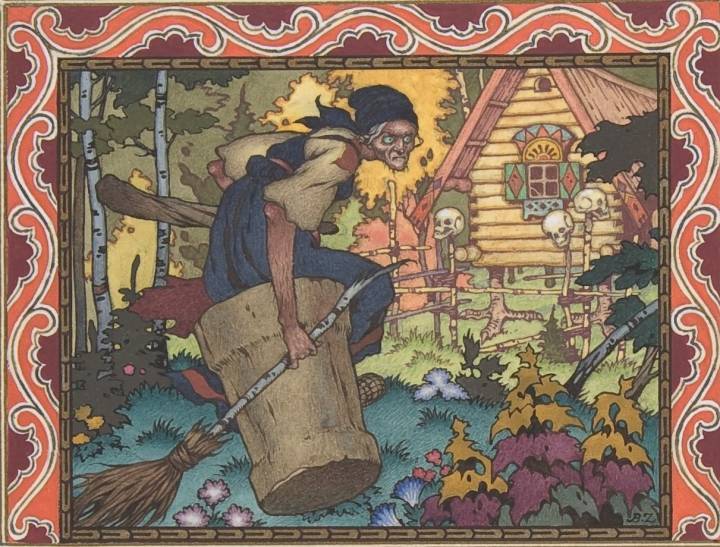

For starters, there’s no word of Baba Yaga ever being a charming seductress—in fact, quite the opposite. She’s seen to be a haggard old woman who lives alone in the dark and damp forest. She is often depicted with a long, crooked nose and sharp, iron teeth, dressed in a long coat, sometimes adorned with a headscarf. She also commonly has a long, wild mane of grey hair, as well as shriveled, drooping breasts, which she sometimes grotesquely hangs over a rod or dumps on her stove.

More often than not, Baba Yaga is described as having one skeleton-leg, which is where her epithet “bony leg” comes from; in some stories, the leg can be wooden or even made of gold. Customarily, Baba Yaga’s face is described as being “wrinkled and withered,” but her eyes are said to be glowing many a time—as if burning with knowledge, enigma and power. She is like that, Baba Yaga: a contradictory force of nature, a mysterious mix of the ugly, the wicked, and the wise, of dark and light.

The objects around Baba Yaga

Aside from her physical appearance, Baba Yaga is often associated with a variety of unusual objects and elements. Most prominently, she is regularly depicted as living in a hut that stands on chicken legs, and is surrounded by a fence made of bones. Moreover, Baba Yaga is also known to ride in a mortar, using a pestle to propel it forward, while wiping away her traces with a broom. Some other objects that are commonly associated with her include a black cat, a cauldron, a spinning wheel, an oven, and even a magical, fire-eyed skull.

Baba Yaga’s hut

It is, indeed, an amazing sight, Baba Yaga’s house: a wooden, forest hut (or, more precisely, an izba), it usually stands on four chicken legs or sometimes—even more impressively—on just one chicken leg. Most scholars believe that this suggests her connection with birds, but it’s quite possible that this is simply a folkloric corruption of an old, traditional way of building homes. Even today, Finno-Ugric and Siberian peoples often build their homes atop stilts or tree stumps—their gnarled roots make them suggestive of chicken feet.

In some fairy tales, Baba Yaga’s house doesn’t stand on chicken legs at all, but on spindle heels. Moreover, it often turns around too, pretty much like the earth itself. Sibelan Forrester marks the connection between the two, revealing that the word for “time” in Russian, vremia, comes from the same vr- root as the word for spindle, vereteno. “A spindle holding up a rotating house where a frightening old woman tests her visitors and dispenses wisdom suggests a deep ritual past,” Forrester writes.

To stop Baba Yaga’s house from turning, the questing hero or heroine of Slavic tales and folklore must order it to stop, and they must do it with a rhymed chant. This little ditty tends to change from one story to another, but it’s usually similar to the one preserved in “The Frog Princess,” wherein Prince Ivan chants the following:

Little hut, little hut,

stand just as you were put—

with your front to my face,

and your back to the wood.

Fences, mortars, and skulls

Baba Yaga’s house is usually surrounded with a fence of bones, which act as posts or poles; to make matters even gorier, these are commonly topped with human skulls, their eyes usually intact. In many of the fairy tales featuring Baba Yaga—such as, for example, “The Death of Koschei the Deathless“—one of these posts is left unadorned, waiting menacingly for the head of the hero. In one story, perhaps the most famous one—”Vasilitsa the Beautiful“—we are provided with a few more macabre details regarding the hut of Baba Yaga. “Instead of door-posts were men’s leg-bones,” the text says; “instead of shutters were arms; and instead of a lock—there was a mouth with sharp teeth!”

In western folklore, witches ride on flying brooms; Baba Yaga appears to favor a mortar, a bowl-shaped tool used to grind and mix ingredients, and pestle, a heavy club-like object used to mash them together. Whenever Baba Yaga is seen riding in this odd contraption, she’s wielding the pestle like an oar to propel her mortar through the air, while sweeping away all of her tracks with a besom. It’s said that Baba Yaga’s mortar and pestle can be seen as symbols of the human reproductive organs, with the mortar representing the female womb and the pestle the male phallus.

In this interpretation, the act of Baba Yaga flying through the air in her mortar and pestle can be seen as a metaphor for sexual liberation, or even sexual intercourse. Indeed, Baba Yaga is a powerful and independent female figure, unconstrained by traditional gender roles. Even though a male partner of hers is never mentioned in any of the tales, she is often depicted as a mother of children, and they are always daughters, never sons. In some stories, Baba Yaga’s parthenogenetically-born children aren’t even humans, but frogs, reptiles, birds, or vermin. In the words of Ugrešić, “Baba Yaga does not only travesty human sexuality: she transvesties it.”

Baba Yaga’s many roles and guises

Even though the basic plot of the stories in which Baba Yaga features is usually the same, she rarely is, if ever. And yet, she always plays an important role, and her character is iconically recognizable in pretty much every story. As Andreas Johns, the foremost expert on Baba Yaga, rightly points out in his dissertation, Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale, her “particular combination of traits and functions makes her unique among witches and witch-like characters in world folklore.”

She is, simultaneously, “an initiatrix, a vestigial goddess, a forest power, and a mistress of birds or animals.” She is also a helpful, but off-putting woman, a frightening witch who preys on children, an enigmatic trickster, a mysterious innkeeper. She is both a figure of fear and a figure of comfort, and her role in the stories can range from a benevolent, if begrudging, helper to a menacing, if vincible, adversary. In some stories she is a source of wisdom and knowledge, while in others she is a symbol of death and destruction. Her behavior and motivations are often unpredictable: no hero—or even reader—knows what to expect when they come across her.

“A Baba Yaga is inscrutable and so powerful that she does not owe allegiance to the Devil or God—or even to her storytellers,” writes Jack Zipes, accurately and astutely. Even so, he does give a succinct outline of her various roles and guises, more than deserving of a quote:

Baba Yaga thrives on Russian blood and is cannibalistic. Her major prey consists of children and young women, but she will occasionally threaten to devour a man. She kidnaps in the form of a Whirlwind or other guises. She murders at will. Though we never learn how she does this, she has conceived daughters, who generally do her bidding. She lives in the forest, which is her domain. Animals venerate her, and she protects the forest as a mother-earth figure. The only times she leaves it, she travels in a mortar wielding a pestle as a club or rudder and a broom to sweep away the tracks behind her. At times, she can also be generous with her advice, but her counsel and help do not come cheaply, for a Baba Yaga is always testing the people who come to her hut by chance or by choice. A Baba Yaga may at times be killed, but there are always others who take her place.

Baba Yaga in popular culture

Sometimes as benevolent as the Italian gift-bearing Befana, other times as cannibalistic and fearsome as the Algonquian wendigo, Baba Yaga is a witch like no other, a complex and multifaceted demigoddess who embodies both good and evil, light and dark, wisdom and whim. It’s only natural that, over the years, she has become a cultural icon in many countries, being reinterpreted and incorporated into various forms of popular culture, from music and art to movies and TV shows.

In music and art

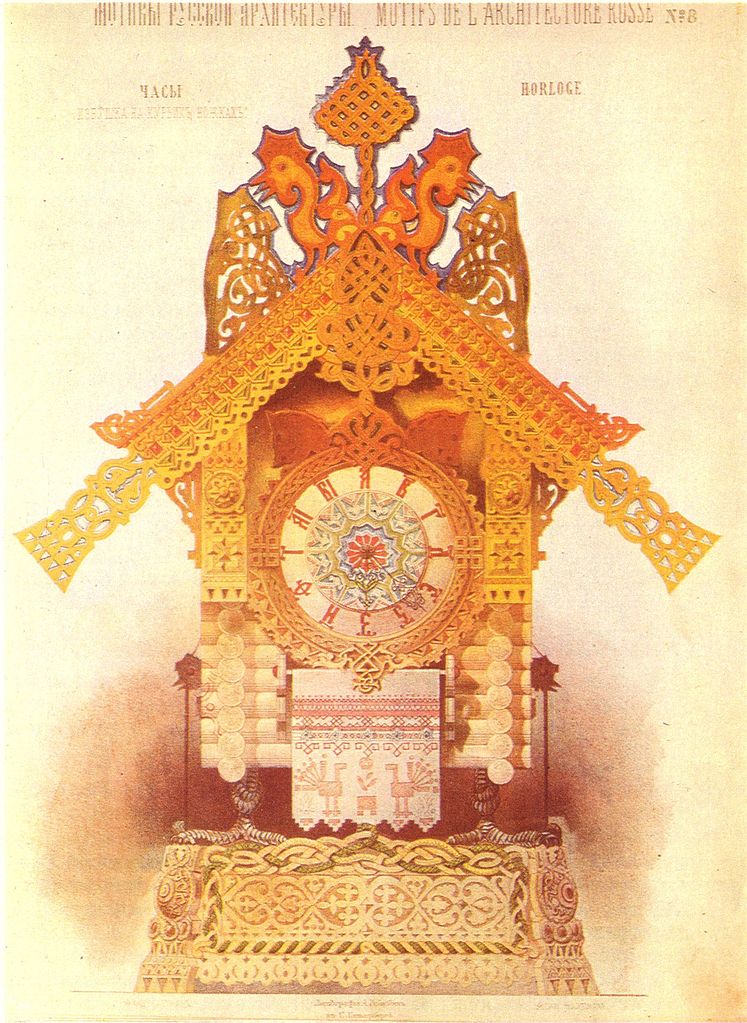

For starters, Baba Yaga has been the subject of numerous musical works. Anatol Liadov’s short symphonic poem “Baba Yaga” is a well-known example, as is the ninth and penultimate movement of Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, titled “The Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba Yaga).” Just like the entire suite, this movement was also originally inspired by a picture by Russian artist Viktor Hartmann, in this case an 1870 painting of Baba Yaga’s hut, adorned with a Russian-style clock.

Hartmann’s painting is one of many representations of Baba Yaga in Russian art, which have helped to popularize her image as a grotesque, sinister and otherworldly sorceress. Perhaps most famous—and influential—among these representations are Ivan Bilibin’s hauntingly beautiful illustrations for “Vasilitsa the Beautiful,” but almost just as memorable are Boris Zvorykin’s drawings for the same fairy tale. Viktor Vasnetsov, Viktor Bibikov and Dimitri Mitrokhin are just a few of the many great Russian artists who have also created their own interpretations of Baba Yaga, ceaselessly trying to capture the strikingly Slavic essence of her mysterious and powerful character.

In movies and TV shows

Just as in Russian art, Baba Yaga is a familiar figure in Russian films too, particularly animated features (Baba Yaga Against!, Babka Ezhka and Others), but can also be seen in other types of productions (Frosty, The Golden Horns). In animation, the prominent Japanese film studio Studio Ghibli has paid homage to Baba Yaga in several of their productions. She is the main antagonist in the 2010 short Mr. Dough and the Egg Princess, and the witch Yubaba in the widely acclaimed Spirited Away from 2001 was directly inspired by Baba Yaga. Finally, the central object in Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) was based on Baba Yaga’s signature walking hut.

The character of Voleth Meir (also known as the Deathless Mother) in Season 2 of the Netflix TV show The Witcher references Baba Yaga in more than one way. Baba Yaga is also referenced in the John Wick franchise, as the codename for the eponymous assassin (played by Keanu Reeves), who is known for his cunning, ruthlessness, and enigmatic nature. Finally, she is a character in the RuneQuest/Gloriantha role-playing game, as well in the 1989 PC game Quest for Glory.

In conclusion

All in all, Baba Yaga is a captivating figure in pop culture, one that continues to inspire and intrigue audiences around the world. Her legacy lives on, and with each new interpretation, she continues to evolve, adapting to the changing times and cultural contexts. Whether seen as a frightening monster, a wise teacher, or a cunning trickster, she remains a timeless icon, a symbol of the power of magic, mystery, and the feminine. Her influence towering, her allure endless, Baba Yaga’s presence will continue to be felt for generations to come.