Napoleon Bonaparte—often referred to as le petit caporal or “little corporal”—is often depicted as somewhat diminutive. Historians and the historically inclined alike generally express their ire at this reputation, not least of all because the widespread fixation on Bonaparte’s stature can detract from more pertinent discussions about his leadership, values, and impact upon history. Napoleon aggressively pushed the ideals of the French Revolution throughout the French-speaking world but was fundamentally disconnected from its spirit.

Nevertheless, we’d be remiss not to address the proverbial elephant in the room, Napoleon’s height. This article will discuss the historical precedent for Napoleon’s typically bantam depiction, which finds its origin in two different spheres: science and British propaganda.

The Napoleon complex

The so-called Napoleon complex is the primary cultural impact of the deliberate depiction of Napoleon’s abbreviated stature.

The Napoleon complex (also called Short Man Syndrome) is a form of inferiority complex considered common among short people—mainly men. The characterization of these individuals comprises such charming personality traits as an aggressive demeanor, socially domineering attitudes, and over-compensatory behavior like self-aggrandizement. The prevailing implication is that such men have offensive and larger-than-life personalities to compensate for their perceived shortcomings.

In 2007, however, researchers at the University of Central Lancashire suggested that the Napoleon complex may be a myth. The study determined that shorter men were less likely to behave aggressively than men of average height.

However, later studies oppose the 2007 Lancashire findings. In 2008, a research team from the Netherlands found taller men to be less jealous in relationships. The research team led by Dr. Abraham Buunk, a professor at the University of Groningen, questioned 100 males and 100 females about jealousy. Dr. Buunk stated: “Taller men tended to be less jealous, and the tallest men were the least jealous.”

In 2018, a team from VU Amsterdam published research affirming the existence of the Napoleon Complex in men. Led by the evolutionary psychologist Mark Van Vugt, the team found shorter men had an increased aggressiveness when dealing with taller male counterparts.

Regardless, the stereotype remains culturally embedded.

French vs. English Imperial measurements

So, the complex may or may not be accurate, but what about the eponymous historical antecedent? How tall was Napoleon? As it turns out, the famous military leader was not extremely short for his time and place, though also not exceptionally tall.

Part of the confusion stems from a misunderstanding of the units of measurement used to determine Bonaparte’s height. The French inch (or pouce) was 2.7 cm, making it longer than the Imperial inch’s 2.54 cm.

Napoleon’s physician, François Antommarchi, reported him to be just over 5 feet and 2 inches (1.57 meters) tall. According to the metric system, accounting for the discrepancy between French inches and Imperial systems brought his stature to about 1.69 meters—just a hair over 5 feet and 5 inches in Imperial units.

Bonaparte’s height thus rendered him no more than an inch shorter than the average height of an adult male at the time. Not exactly an NBA draft pick, but not comically short, either. Bonaparte’s measurements left him the butt of a joke that grew at least partially out of a cultural misunderstanding.

James Gillray and cartoonist propaganda

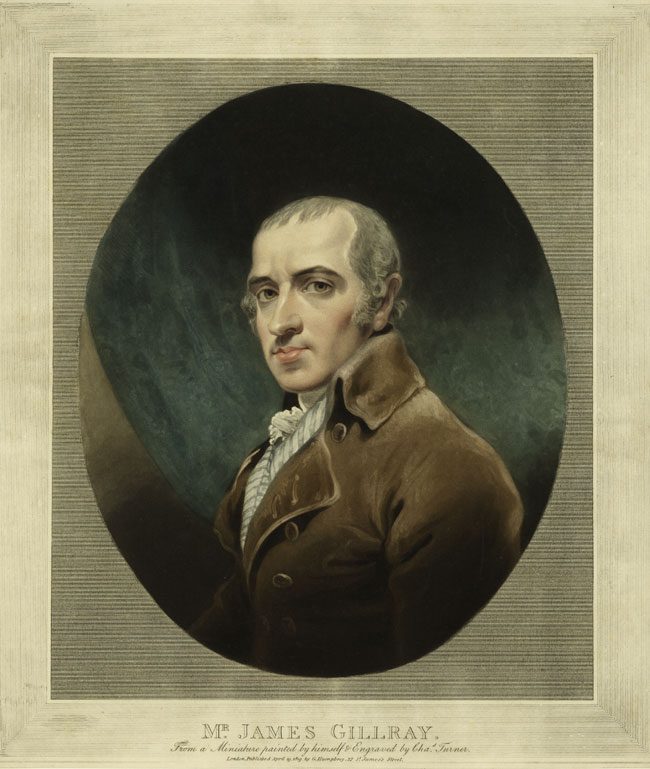

If the jape of Napoleon’s stature was only partially the result of measurement discrepancies, what else contributed to the Emperor’s diminutive reputation? Primarily an Englishman by the name of James Gillray.

Gillray was a British political cartoonist most famous for his political satire. He was prolific in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: the height of the Napoleonic Wars. Naturally, the tiny king himself was the object of much of Gillray’s scathing wit.

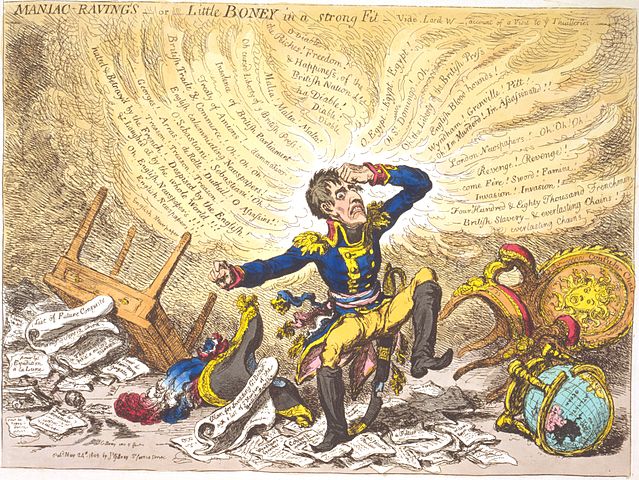

Gillray’s depiction of Napoleon Bonaparte gradually evolved from an aggressive (and at least average-sized) warmonger filled with vim, vigor, and viciousness to the more familiar truncated caricature below.

The cartoon Maniac-raving’s—or—Little Boney in a strong fit was a watershed. Published in 1803, it was the first time Gillray depicted Napoleon as a short-statured brat with little temper control after an actual incident at the Tuileries Palace in Paris.

Napoleon aimed a withering verbal attack on Charles Whitworth, the British Ambassador to France. Hundreds of dignitaries witnessed the tirade directed at Viscount Whitworth. Bonaparte’s outburst was an attempt to shock and confound the ambassador and expose him as weak and afraid. Whitworth remained unruffled in the face of Bonaparte’s onslaught. His stern composure caused Napoleon to project an impression of petulance and childishness. By modern standards, a public relations disaster.

When word of the incident reached English shores, Gillray wasted no time jumping on Bonaparte’s developing reputation as a moody brat incapable of real diplomacy. The sensational cartoon shows a minuscule but enraged Napoleon tearing his hair out, surrounded by overturned furniture as big as himself.

Not only did the nickname “Little Boney” delight the public, but the depiction of the French Emperor as small, angry, and boastful would inform all of Gillray’s future caricatures of the le petit caporal.

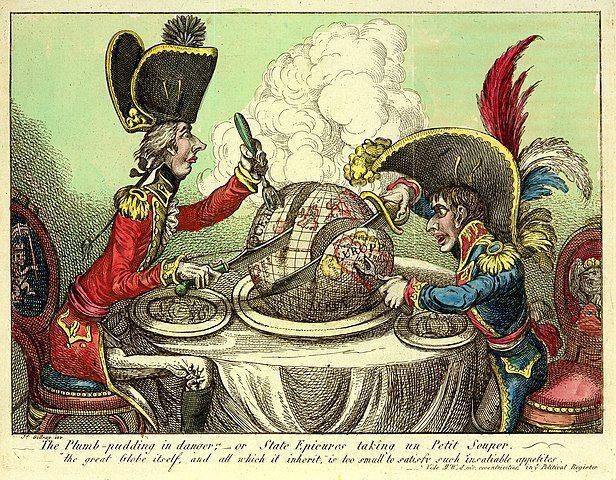

Gillray’s 1805 cartoon The Plumb-pudding in danger is considered the most famous political cartoon in history.

The seminal work shows the British Prime Minister William Pitt and Napoleon Bonaparte, newly crowned as Emperor of France. The two figures, dressed in military uniforms, are carving up a plum pudding in the shape of a globe of the Earth into spheres of influence. Napoleon, much smaller than his British counterpart, is required to stand up to use his carving knife.

The cartoon is a satire of the peaceful advances that Napoleon had made in January of that year. The brief Peace of the Amiens treaty between Britain and France directly resulted from Napoleon’s call for reconciliation with Britain. This momentary halt to hostilities ended when Napoleon threatened to invade Britain.

In Gillray’s depiction, Pitt’s fork is a trident, referring to Britain’s naval might, especially following the decisive British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar.

An angry Napoleon is aggressively carving a section labeled “Europe,” though the islands of Britain and Ireland are conspicuously excluded from Napoleon’s helping. His share is also notably much smaller than that of his counterpart.

The immense popularity of Gillray’s satirical cartoons cemented the use of propaganda as an effective tool to diminish the image of a powerful tyrant to that of a tantrum-prone brat in the eyes of the public, disarming Napoleon of his fearsome reputation. His routine calls on the British government to censor their media—primarily ignored—shows that the press managed to wound Napoleon’s image in a way that a military loss could not.

Napoleon’s autopsy

The circumstances of Napoleon’s autopsy cast some doubt on the recorded measurements. As mentioned above, Bonaparte’s physician, François Carlo Antommarchi, gave Napoleon’s height as 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 meters) at the time of his death on the island of Saint Helena.

Several British doctors signed off the autopsy. British involvement has prompted uncertainty that Bonaparte’s height was recorded in French instead of British measurements. Historians generally agree that French measurements were used, but doubt remains over the actual height of Napoleon Bonaparte.