In the 2019 adaptation of Little Women, the character Amy March, portrayed by Florence Pugh, addresses her old neighbor and love interest, Laurie, with a stern lecture on marriage:

Well. I’m not a poet, I’m just a woman. And as a woman, I have no way to make money, not enough to earn a living and support my family. Even if I had my own money, which I don’t, it would belong to my husband the minute we were married. If we had children, they would belong to him, not me. They would be his property. So don’t sit there and tell me that marriage isn’t an economic proposition because it is. It may not be for you, but it most certainly is for me.

Though not an exact quote from the original novel penned by Louisa May Alcott in the late 1860s, these words encapsulate the struggle against coverture that Alcott was highlighting. Coverture was an archaic Anglo-American legal doctrine that rendered a married woman legally subordinate to her husband. Under this system, a wife could neither own property nor engage in business transactions without her husband’s consent.

This lack of autonomy played a substantial role in denying women’s suffrage, as voting rights in 18th-century America were often tied to property ownership. However, not all women were confined to the status of feme covert. In the same century, history records the case of Lydia Taft, a wealthy widow in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, who voted as a feme sole or femme sole, a single woman with independent legal status.

In an era marked by societal pressure for women to secure good husbands, the feme sole status became an object of envy for many married women. The complex and often conflicting attitudes surrounding marriage, the legal status of unmarried women as feme sole, and the tortuously slow progress toward equality within marriage form a layered and compelling narrative.

The persistence of these inequities is brought into stark relief when considering that women in the United States were unable to secure a line of credit, including a mortgage, without a male cosigner until 1974. Similarly, the recognition of marital rape as a crime is a startlingly recent development, only having been codified in 1976.

Historical roots of feme sole and feme covert laws

With roots in the Norman French terms introduced to England during the Norman invasion of 1066, the legal concepts of feme sole and feme covert have played a crucial role in defining women’s rights throughout history.

These legal terms emerged from the Catholic belief that upon entering the sacred bond of matrimony, a man and woman become one flesh and blood. This unity meant that the husband assumed the singular legal identity that represented both himself and his wife, along with their children. From the high and late middle ages onward, married women in England were thus deprived of the ability to conduct business, sign legal documents, or assume significant financial responsibilities independently.

Unmarried women, however, were a different case. Although most single women remained under their fathers’ control until marriage, there were single women who were never married, widowed, or divorced. They had to act on their own behalf. For these women, the Norman term feme sole applied, granting them the same legal status as men.

The recognition of married women who required feme sole status came quite early in history. By the 1330s, legal texts referenced married women with feme sole status, primarily independent businesswomen who needed to engage in legal contracts for their enterprises. These women were known as feme sole traders, and their rights were specific to their business dealings without extending to the home.

Examples also exist of women obtaining feme sole status within marriage through legal means such as prenuptial agreements. These cases typically involved wealthy women with inherited property.

While exceptions to the rule of coverture did exist, it’s essential to recognize that women who lived outside the patriarchal hierarchy, therefore those with feme sole status, were disproportionately persecuted during the witch trials spanning the 15th to the 18th centuries.

Progress came with the passing of the Married Women’s Property Act in the United Kingdom in 1870. This landmark legislation granted women the legal right to own the money they earned and inherit property independently, laying the foundation for further strides toward gender equality.

Coverture in the United States and the women’s rights movement

The doctrine of coverture, a legal concept inherited from English law, firmly established itself in early America. According to this principle, a married woman was referred to as a feme covert, legally subordinate to her husband, while single women enjoyed feme sole status, signifying legal independence.

The discontent with this arrangement began to surface in the 18th century. Abigail Adams, in her correspondence with her husband and future president John Adams in 1776, pleaded for the consideration of women’s status in the shaping of the new nation’s laws:

In the new Code of Laws, which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember, all Men would be tyrants if they could.

John Adams dismissed her concerns with a laugh and made no provisions for married women’s liberties in his legal drafts. Thus, the struggle against coverture became a central issue in the women’s rights movement over the next century, even overshadowing the right to vote.

In the 1840s, John Neil, the first women’s rights lecturer, pinpointed the legal subjugation of women within marriage as the primary hindrance to the movement:

How long [women] shall be rendered by law incapable of acquiring, holding, or transmitting property, except under special conditions, like the slave?

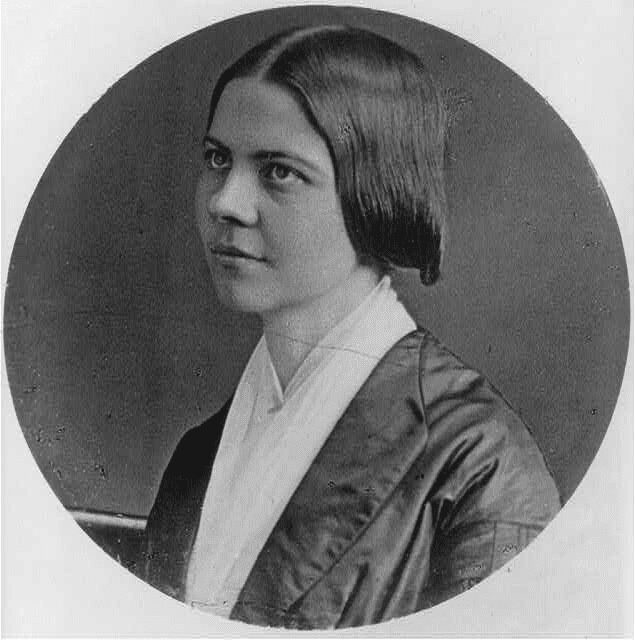

The 1850s saw women’s rights activist Lucy Stone identify coverture as the foremost battle for women’s rights, critiquing the common law of marriage that placed wives under husbands’ “custody.” Even though Stone chose to keep her maiden name after marriage, she found herself legally subordinated to her husband, unable to own property or enjoy independent legal status.

The slow march toward women’s rights in 19th-century America was fraught with challenges. A nearly violent dispute erupted at the 1853 World Temperance Convention over whether women, seen as second-class citizens, should be allowed to speak. In 1862, the North Carolina Supreme Court refused a woman a divorce after her husband horsewhipped her, ruling that he was within his legal rights under coverture.

Progress was gradual but determined. Starting with Mississippi in 1839, coverture laws were dismantled state by state. However, elements lingered into the late 1960s, such as restrictions on women obtaining independent lines of credit.

The women’s suffrage movement achieved the right to vote in the 1920s, but it wasn’t until 1966 that the United States Supreme Court declared coverture obsolete. Even then, remnants of the doctrine persisted in common law across several states.

This tumultuous history of coverture paints a vivid picture of a society grappling with gender inequality, illustrating the relentless struggles, victories, and setbacks that shaped women’s legal independence in the United States.

Surprising consequences of coverture

In the United States today, the concept of coverture and its impact on women may seem like distant history, yet its echoes lingered well into the modern era. Consider the following:

- Passports: Until the 1930s, married women were unable to obtain individual passports, instead being included on their husbands’ documents, much like young children. The notion of a married woman traveling alone without her husband was unthinkable until then.

- Jury Service: Not until 1968 were women universally recognized as capable of serving on juries across all states, marking a significant step towards equality in the eyes of the law.

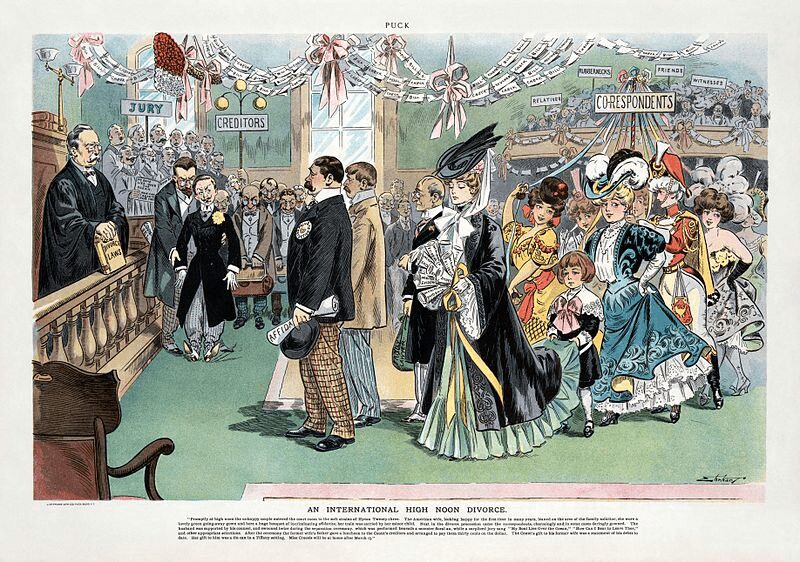

- No-Fault Divorce: In 1969, California’s then-Governor Ronald Reagan signed no-fault divorces into law, a reform that had already been implemented in Russia in 1917. Before this, legal divorce required proof of adultery, abuse, or abandonment, creating substantial barriers for women seeking to leave a marriage.

- Employment Restrictions: Until the 1970s, many states banned women from certain occupations, including mining and bartending, supposedly to protect their health or morals. Some even imposed limitations on women’s work hours outside the home, reinforcing stereotypes of women’s domestic roles.

- Dress Codes in the Senate: In an illustration of how entrenched gender norms can be, women were not permitted to wear trousers on the Senate floor until as recently as 1993. While not related to marriage or legal status, this rule serves as a comical yet sobering example of how slowly progress can be made in women’s self-determination, even in the face of seemingly arbitrary limitations.

These remnants of a time when women’s legal and social autonomy was severely restricted offer a striking perspective on the journey towards gender equality in America. They provide a stark contrast to contemporary understandings of women’s rights and illustrate the resilience and perseverance required to change entrenched societal norms.

It is a vivid reminder that the path to equality has been neither smooth nor swift and underscores the importance of vigilance and commitment in ensuring the continued advancement of women’s rights and freedoms.