Glass is everywhere in modern life, which, you would think, makes it unremarkable. But not all glass is made by humans. Some glass is natural, such as Libyan Desert Glass—which has been found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun, an ancient Egyptian pharaoh.

How glass is formed

Glass is simply sand that has been heated until it melts. The sand needs to be heated to approximately 3090°F (1700°C) to form it into glass.

When the sand cools, it doesn’t turn back into solid matter, as other liquids do. Instead, the sand becomes something different. It’s almost, but not quite, a solid. Scientists generally refer to this as an amorphous solid: a substance between liquid and solid but has the characteristics of a solid; that is, you can hold it.

Glass is great because it’s transparent, cheap to make, and easy to shape when molten, but inert when set. You can also recycle it an unlimited number of times.

The glass we use daily is actually a mixture of sand, sodium carbonate, and limestone. The sodium carbonate lowers the melting point of sand, making it cheaper to produce. Unfortunately, it also makes the glass dissolve in water. For this reason, limestone is added, as it stops the glass from dissolving.

What’s special about Libyan Desert Glass?

Libyan Desert Glass is special because it’s not made by humans. That’s impressive because there are few opportunities in nature for sand to reach a melting point.

Libyan Desert Glass is a naturally occurring glass. Though it was first discovered in 1932, it was actually formed approximately 26 million years ago.

Scientists don’t know exactly how it was formed, although there are several theories.

The most likely scenario is that a meteorite made contact with the Libyan desert and was hot enough on contact to bring the almost pure quartz sand to melting point. The fact that it was almost pure quartz sand is what allowed glass to be formed instead of crystal structures.

Since Libyan Desert Glass can be found over an area of hundreds of square miles, the meteorite that impacted the desert would have had to have been extremely large.

This theory is supported by the recent discovery of reidite, a rare mineral, which is created when zircon, a common mineral in sandstone, is compressed. Under extreme pressure and high temperatures, zircon becomes reidite. However, the heat of the meteorite would then have caused the zircon to recrystallize, leaving no apparent trace of the reidite, which confirms the meteorite impact.

Fortunately, modern science has developed electron backscatter diffraction, a technique that can identify if redite once existed in specific substances. Tests indicate positive results in Libyan Desert Glass.

This makes a strong case for the creation of Libyan Desert Glass by a meteorite, but it’s not a definitive answer.

The alternative is an explosion in the upper levels of the atmosphere that was hot enough to heat the desert and create the same effect. This explosion could have been an asteroid burning up in the atmosphere, never quite touching the ground.

Man-made “natural” glass

Most glass is made by humans melting sand in a controlled process. But there have been times when humans have mimicked nature inadvertently.

The most obvious example was Trinity, the detonation of a nuclear device by the United States Army. The test was performed on July 16, 1945, at White Sands, New Mexico. The sand sucked up by the explosion returned to the ground as molten glass.

Libyan Desert Glass and other amorphous solids

Glass is not the only example of an amorphous solid, which is any substance that appears solid but does not have a regular crystalline structure.

If you look at sand through a microscope you’ll see individual molecules arranged in a regular pattern. Sand, and other materials that cool rapidly, don’t have time to recreate this regular pattern. This means the molecules are irregular.

Read more: Last Dinosaur Found: African T-Rex Discovered in Moroccan Mine

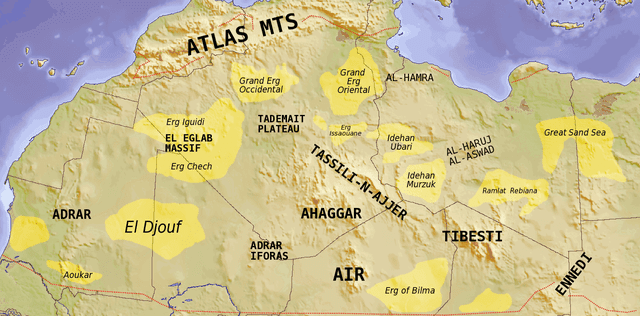

Despite the harsh conditions, scientists have undertaken expeditions to the Libyan Desert. Their research shows the composition of Libyan Desert Glass to be quartz from the dunes and sandstone from the Nubia Formation underneath the Great Sand Sea.

The distribution of materials supports the theory of a sudden explosion of heat followed by slow cooling. It also suggests that the mass of glass currently located is only a fraction of what there could be. Scientists estimate there could be 10,000 times more Libyan Desert Glass.

Other examples of natural glass

Libyan Desert Glass is tinted green, yellow, or brown. The color is part of what makes it so precious and unique. The size of the area that was turned into glass is huge, introducing an array of extra minerals into the equation, which affect the coloring of the glass.

Of course, natural glass appears in other places around the globe, above and below the surface of the earth. For example, glass sponges that live in the depth of the ocean actually possess silica skeletons. These are surprisingly similar to optical fibers and their makeup mimics glass.

Lightning striking sand can also cause the sand to melt and form glass. But these are small tubes of glass.

What makes Libyan Desert Glass so unique and precious is there are no other known incidents of naturally occurring glass on this scale. You may not be able to plan an expedition to the Libyan Desert, but you can certainly consider the power of nature next time you look at a piece of glass.