Litha is the most common name Neopagans use to refer to the day of the summer solstice, June 22. It is one of the four Lesser Sabbats, the dates of which correspond to the English quarter days, that is to say, the solstices and the equinoxes. Together with the four Greater Sabbats (the midpoints between the quarter days), the Lesser Sabbats make up the “Wheel of the Year,” an annual cycle of major holidays observed by the Neopagan Witches around the world.

Better known as Midsummer’s Eve, Litha celebrates the longest day and the shortest night of the solar year. Its iconography forms an important part of the popular imagination in the British Isles. Even in the 21st century, the day is noted for the burning of bonfires, and for widespread revivals of ancient northern European beliefs. All in all, it’s a nice day for a… pagan wedding.

A 1970 Midsummer pagan wedding

June 22, 1970, late evening. Tender candlelight shimmers against a pair of arched Gothic windows that flank the sides of an eccentrically anachronous New York City apartment. Inside, a Wiccan priestess explains to an enamored couple of 20-somethings that Witches are not Satanists and that their traditions are as old as time itself. Rather than the Prince of Darkness, they worship the elements, the ancient forces of nature, the god of the hunt, and the Triple Goddess—the Great Mother of all that exists. It’s the oldest universal religion, she says, a tradition that predates Judaism and Christianity by thousands of years.

Next, she leads the couple through a set of seemingly unyielding rituals. She tells them to face each other and hold right and left hands together, so that their clasped hands, when seen from the top down, form the number eight—or rather, the figure ∞, the sign of infinity. As she ties a cord around the girl’s left wrist and the boy’s right wrist, she recites an invocation of the elements and the Triple Goddess: “By wood and stone, by wind and fire, by land and water, I bring you in! Death does not part, only lack of love, and the vow is forever in the Goddess’s sight…”

Later on, the priestess makes two small cuts on each partner’s forearm, and mixes their blood into a consecrated cup of wine. After promising to love each other forever, the partners take a sip from the cup and are asked to exchange rings. The boy gives the girl a silver claddagh, the traditional Irish wedding ring, and in return she gives him a matching golden one. To finalize things, the partners step over a broomstick. The priestess presents them with two identical hand-printed documents, in English and in witch runes, and declares them wedded. The girl is jubilant and proud. The boy—so caught up in the unity ritual until then—faints in a mixture of ecstasy and exhaustion.

The birth of modern pagan wedding ceremonies

What we described above is, arguably, one of the earliest high-profile Neopagan weddings in history, as imaginatively outlined in Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman’s 1980 book, No One Here Gets Out Alive—the first biographical account of the life of American rock star Jim Morrison, the boy in the wedding ceremony. Though nearly not as famous, the girl was, at the time, a celebrity as well: Patricia Kennealy, the editor-in-chief of the influential Jazz & Pop magazine, and one of the first women rock critics to make a name for herself. Almost as soon as the couple’s pagan wedding was recreated for the 1991 Oliver Stone biopic, The Doors—with the actual Kennealy portraying the Neo-Celtic wedding officiant—it launched a thousand copycat versions in movies, TV shows, and most importantly, real life. Illegal for centuries and clandestine for decades, pagan wedding ceremonies suddenly turned mainstream.

The time was ripe—and right—for it. Just 20 years before Morrison and Kennealy wed, in 1951 to be exact, the Witchcraft Act of 1735 (which made it a crime for anyone to claim that a person might have magical powers) was finally repealed in Britain, giving occultists and spiritualists in the country the legal authority to carry out religious wedding ceremonies in their own fashion, without the fear of being persecuted. Needing a word for their wedding rituals not associated with Christianity or legal marriage (since, at the time, there were no legal Pagan clergy), early English Wiccans Gerald Gardner and Doreen Valiente dusted off an old and out-of-use dictionary term, and reinvented its dictionary meaning: handfasting.

Now, originally, handfasting was a humble Christian ritual, the equivalent of a modern-day formal betrothal or, even more frequently, a common-law marriage. It was most often performed by peasantry, in lieu of a church wedding ceremony, and was rarely more complex than a couple exchanging homemade rings after joining hands and declaring themselves united. Due to a scholarly misunderstanding (possibly of long Viking engagements), between the 18th and the early 20th century, handfasting was mistakenly believed to be a kind of trial wedding, lasting for a year and a day. Ever since Neopagans started using it to refer to their own religious ceremonies, from the 1960s onward, the term has acquired a new meaning, becoming an alternative to the Christian concept of marriage.

How pagan handfastings differ from traditional Christian marriages

“It is often said that handfasting is the Wiccan equivalent of marriage, but that is not a very accurate statement,” American academic James R. Lewis writes in Witchcraft Today, an influential turn-of-the century encyclopedia of Wiccan and Neopagan traditions. Handfasting, he goes on to explain, is not just a formal religious ceremony, but a unique unity ritual, which creates “a magical partnership between two people, for the purpose of working magic, and especially sexual magic, together.” In Lewis’ exegesis, handfasting shouldn’t be confused with Christian marriage as it differs from it in at least three important ways.

1. The couples make their own vows

Even though things are admittedly not as strict in the 21st century as they were in the past, in most traditional Western Christian marriages, marriage vows are defined by law, or at least strictly outlined by various religious scripts and practices, most of them (in the English-speaking world) deriving from the Sarum rite of medieval England.

In Catholicism, for example, the Rite of Marriage (#25) offers several similarly-worded options, the most common one being, “I, ____, take you, ____, to be my lawfully wedded (husband/wife), to have and to hold, from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, until death do us part.” Most other churches use similar vows, with Lutherans adding “and I pledge to you my faithfulness” at the end. Finally, as prescribed by the Book of Common Worship, the usual vows in Anglicanism end with, “…according to God’s holy law, in the presence of God I make this vow.”

In contrast, the vows in pagan handfasting ceremonies are completely flexible, limited only by the imagination of the prospective spouses. They get to choose what to say to each other, and in which way to say it. They also get to choose the god or the goddess who will oversee the wedding ceremony, and even the invocation that summons the respective supernatural being.

2. Handfastings exist independently of legal and religious marriages

Until the Witchcraft Act of 1735, handfasting was recognized as a legal act of marriage in England and most of its domains. Nowadays, it is primarily a symbolic ritual: although it is legal to carry out a handfasting ceremony in most of the developed world, almost nowhere recognizes it as a legally-binding marriage. But that’s what makes it so attractive.

“Two people who are handfasted as magical partners in a circle may each have legal spouses as well, who may or may not be members of that circle,” explains Lewis. Just as well, a legally married couple can decide upon a handfasting ceremony as a way to solidify their relationships with one another. Finally, a person may choose to have multiple handfastings, and just as many handfasting partners, for whatever reason seems appropriate.

Since it doesn’t define the partners involved in a handfasting ceremony as belonging to one another, modern paganism recognizes all these forms of “marriage” as equally valid. Legally, however, things are not as clear.

3. A handfasting can be for a set period of time

In the original pagan tradition—as de facto delineated by the Father of Wicca, Gerald Gardner—the handfasting partners were expected to vow to each other “their present life and all their future lives to come.” Since Gardner believed that people could travel mentally in time along the Akashic records, he also believed that a Wiccan wedding was a sort of transhistorical promise to faithfulness. Put simply, the partners were expected to renew their vows as they met, again and again, in all of their future reincarnations.

Modern pagan weddings are much less rigid and allow all kinds of different condition-based pledges. For example, during a handfasting ritual, a couple can vow to remain with one another “so long as their love lasts” or “so long as their love helps them grow, each in their own way.” However, most common are handfastings set for some traditional period, such as “a year and a day” or “seven years.” Since this is a symbolic and not a legal commitment, when the handfasting period is over—the handfasters are free to do as they like. In the words of Lewis, “no one needs to enrich any lawyers or courts.”

A modern pagan wedding ceremony

In the early Gardnerian days of modern paganism, handfastings were pretty strict and closed rituals, and were deliberately designed to be as different as possible from church weddings. Nowadays, though, they have evolved to include many more conventional religious elements, even such that can be considered Judeo-Christian in nature. In the process, most pagan wedding ceremonies became less rigid and more diversified, turning into a sort of “collage of cultural traditions,” as Raven Kaldera and Tannin Schwartzstein remark in Welcoming Hera’s Blessing: Handfasting and Wedding Rituals. Even so, there are certain aspects that most pagan weddings share and are all but universal.

1. The setting

A pagan wedding ceremony is almost always held outside, the only place where the four elements can be properly honored. Even though not all handfastings incorporate elemental invocation as well, most do.

The invocation can be a set of vocal formulas, or it can be a combination of a few simple actions, each of which should correspond to a certain element, and be done in a different direction—like, for example, sprinkling salt to the north, lighting a candle to the south, pouring water in a cup while turned westward, and waving a fan at the easternmost point of the wedding area.

This is only an illustrative example, of course. Elemental invocations can be much more imaginative and complex. For example, Kaldera and Schwartzstein tell of a beautiful musical invocation they had the honor of witnessing, during which half a dozen people invoked the elements by playing different types of instruments: deep drums for earth, light doumbeks for fire, bells and chimes for wind, and harp and rattles for water.

2. Circle closings

The proper pagan wedding begins with the encirclement of sacred space. In the simplest form possible, this can be achieved by having the high priest or priestess walk all the way around the prospective wedding area.

Most pagan ceremonies tend to be a bit more elaborate than that, and one should expect the wedding officiant to delineate the sacred space by other visual or auditory means, most of them corresponding to the elemental forces—such as sprinkling water or glitter, beating a drum or tinkling wind chimes, and even waving a sword or a wand.

Either way, the idea behind this traditional custom is quite simple: to consecrate the space wherein the commitment ceremony is supposed to be performed, thereby making it adequate for a proper pagan celebration of love and loyalty. Most pagan rituals, marital or not, begin with a similar observance.

3. Deities and invocations

Once the elements are invoked, and the circle closed, the Wiccan priest or priestess welcomes the wedding guests and calls upon a god or goddess to bless the couple’s future.

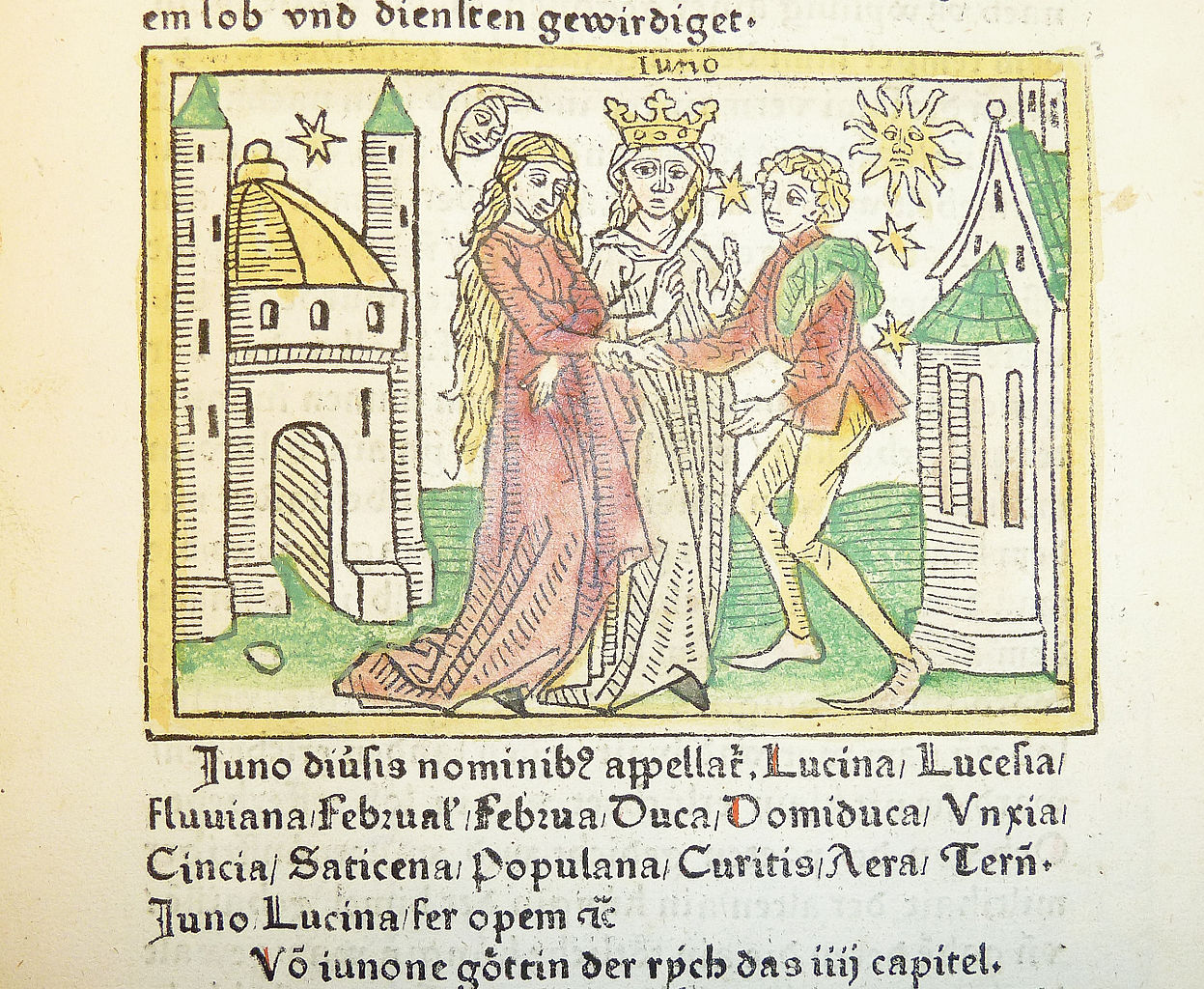

No pagan wedding ceremony is complete without an invocation of a supernatural being. Unlike in Christianity, in modern paganism, this being is usually female, for the simple reason that most guardian deities of marriage in ancient pagan religions were goddesses, the Greek Hymen, and the Egyptian Bes being the only two notable exceptions.

However, Hera and its Roman twin Juno, Persephone and its Roman equal Proserpine, Aphrodite and its Norse counterpart Frigga—to list just a few names—are far more commonly invoked and celebrated deities at modern pagan weddings.

4. Handfasting

Perhaps the handfasting ritual is the most conspicuous and, arguably, most commonly known element of a pagan wedding ceremony. Traditionally, it consists of three parts:

- First, the wedding officiant asks the bride and the groom to face each other and cross their hands. This establishes the so-called “infinity position,” as the couple’s bodies, when seen from above, make up a horizontal version of the number eight—that is to say, the mathematical symbol of infinity.

- Then, an individual of the couple’s choice—commonly a child, the maid of honor, or the best man—ties a cord around the bride’s left wrist and the groom’s right wrist. Ideally, the couple should stay bound together throughout the entire reception.

- Finally, with their hands bound together, the partners are asked by the officiant to proclaim their vows.

It is to the bride and the groom (or, if they prefer, their pagan wedding planners) to decide on the type and color of their wedding cord. They can also choose whether they’d prefer braiding several cords together, or picking a single cord in a color meaningful to both of them.

Predictably, each color symbolizes something different. For example, red symbolizes passion, pink—childhood and childlike joy, and blue—serenity and bliss. Green symbolizes springtime and new beginnings and seems to be the most popular choice among pagan couples. On the other hand—and probably due to its association with traditional Christian weddings and virginity—white is the least likely color to make an appearance at a pagan wedding ceremony.

5. Vows

When it comes to marriage vows—as we already noted—a pagan wedding ceremony differs substantially from a Western Christian wedding in that it uses no fixed formulas or ready-made pledges. It would be more precise to say that, unlike in Christianity, in modern paganism, vows are completely up to the couple: if they want to, they are allowed to use even preprepared oaths.

In that regard, pagan wedding vows may be grouped into two different types: spoken and repeated. Spoken vows are recited by the handfasted partners as they face each other, from memory and without the aid of the clergyperson. In contrast, repeated vows—as the name suggests—have the priest or priestess reading off the ready-made vows and instructing the happy couple to repeat them back at the agreed upon moment.

Many pagan couples choose to hold two handfasting ceremonies. The first one is “a term handfasting,” and usually lasts for a year and a day, or sometimes even seven years. After the allotted time interval—and provided the partners are still in love with each other—a second handfasting is organized. This one is either conditional (“so long as love shall last”) or, in rare cases, eternal (“for this life and all lives to come”).

6. Presenting the rings

It seems that no wedding ceremony can pass without a ring—not even a pagan one. But after all, in the words of Kaldera and Schwartzstein, “It is no accident that the symbol of marriage is the ring: the circle that never ends, includes everything, and is penetrated by the finger that cannot stand alone.”

In most pagan weddings, traditional or pseudo-Celtic rings are exchanged, the most popular being the Claddagh ring—a special type of a fede ring that first appeared in 18th-century Galway, in which two hands clasp around a crowned heart. Each of these elements symbolizes an important aspect of a shared life: the crown stands for loyalty, the heart for love, and the clasped hands for eternal friendship.

7. Jumping the broom

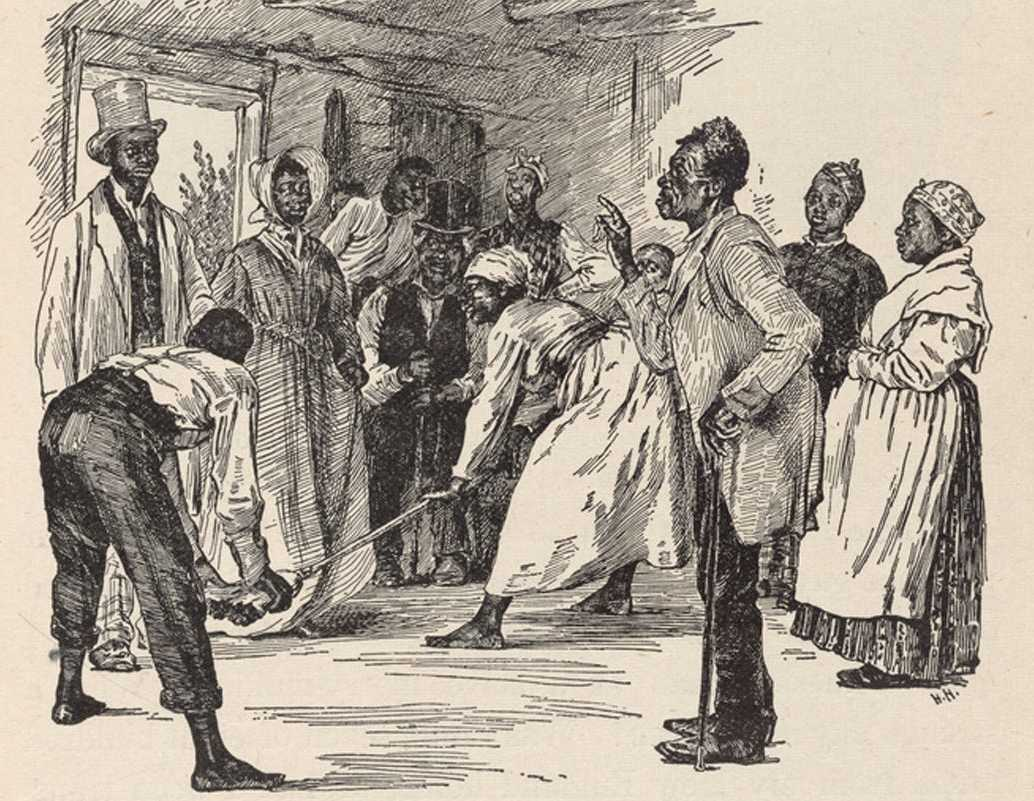

Traditionally, a pagan wedding ceremony concludes with a curious little custom whose origins can be traced back at least to 18th-century England, and which was especially popular among American antebellum slaves.

Called “jumping the broom,” the custom consists of the newlyweds leaping hand in hand over a besom held horizontally before them, a little above the ground. Although originally the practice symbolized a mock-marriage, in modern paganism, it is meant to represent the crossing of the symbolic boundary between the couple’s old lives and their new, shared, one.

After the broom jumping, the bride and the groom’s hands are finally untied as a memento that they are still individuals and have chosen of their own free will to trade their personal freedoms for a communal life. As in almost any pagan ceremony, what follows after is a feast—and an elated celebration that includes everyone present.