When we humans reshape our planet, we try to do it deliberately, in the pursuit of some grand economic or political goal. Think of the Panama Canal connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific, or the vast areas of the Netherlands that have been reclaimed from the North Sea. Other times, however, our immense technological power gets the better of us, and events escalate far beyond any human control. One such instance can be found in Lake Peigneur, Louisiana. Today it is a brackish body of water, with a maximum depth of 200 feet (60 m) which makes it the deepest lake in the state. It didn’t start out that way. In 1980, oil drillers at Lake Peigneur punched through the roof of a salt cavern and caused the entire lake to drain underground, swallowing up millions of dollars worth of equipment while transforming the landscape in an instant. Read on to discover the truth behind this unusual man-made disaster.

Prelude to the disaster

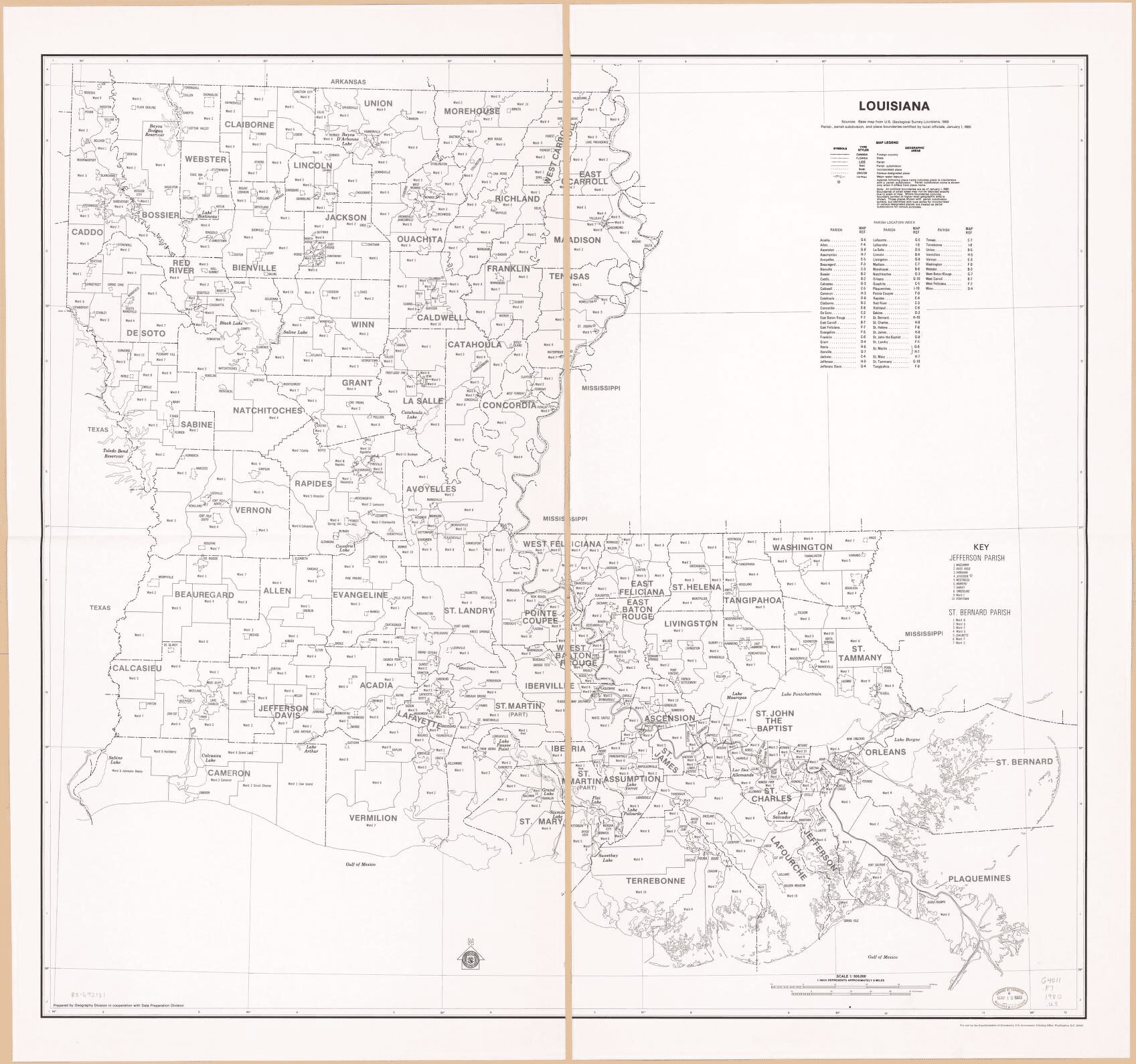

Lake Peigneur is located in the far south of Louisiana. Prior to the accident, it was an unremarkable freshwater lake, ten feet (3 m) deep, and popular among local fishermen. Its total area was about 1,000 acres (4.05 sq. km). A small shipping channel, the Delcambre Canal, drained it into Vermilion Bay in the nearby Gulf of Mexico. Numerous private residences surrounded the lake; on the south shore lay the Live Oak Gardens, a nursery for tropical plants that brought many tourists into the area.

The Diamond Crystal Salt Company

In late 1980, two companies were undertaking parallel—and, as it turned out, disastrously uncoordinated—extraction operations in the vicinity of the lake. The Diamond Crystal Salt Company maintained an active mine at nearby Jefferson Island, with many of its excavations taking place underneath Lake Peigneur. This mine had been running profitably for many decades. By the time of the accident, it had carved a huge volume out of the Earth, creating what amounted to enormous manmade caverns in the salt dome.

Texaco, Inc.

More recently, the petroleum company Texaco had come in and set up two oil wells, both of them operated by independent contractors under the oversight of Texaco specialists. The No. 35 well stood atop solid ground near the shoreline; the other, known as P-20, was situated out on the open water, atop a specialized drilling platform serviced by barges. Operations began at the P-20 site on November 17. For the first couple of days, progress was routine, reaching 992 feet (302 m) by 6:00 PM on November 19. No one on the rig, or in the mine down below, had any idea what was about to happen.

The drill meets the mine

On the morning of November 20, the drill bit suddenly seized up. It had, by that point, reached a depth of 1,248 feet (380 m). The crew of the oil rig attempted to get it started again, to no avail, and soon they started to hear strange popping sounds from down below—something had gone very, very wrong. Even more ominously, the platform began to tilt. As one corner of it sank into the lake, the foreman gave the order to abandon ship, loading crew and equipment onto a barge and ferrying them to safety. Less than two hours later, the crew watched dumbstruck as the entire drilling rig disappeared into what they had thought to be shallow water.

Meanwhile, far below, Diamond Crystal had 55 employees working in the salt mine. Electrician Junius Gaddison was the first to notice that something was wrong. He heard a banging noise, which turned out to be the sound of fuel drums crashing together as a stream of muddy water carried them down the tunnel. He wasted no time alerting the others, and within minutes the evacuation signal went out to the entire mine, compelling everyone to drop what they were doing and get out of there. The miners first traveled on foot and by mine carts to the highest level of the facility. Next, they had to take the elevator to the surface, ferrying eight men at a time as water from Lake Peigneur rushed in around them. Altogether, the evacuation was completed quickly and professionally, and it ended in total success—all 55 men escaped without a scratch.

Catastrophic collapse

While everyone involved had escaped danger, the disaster wrought quick havoc on Lake Peigneur and its environs. The vast, hollowed-out cavities of the mine were more than enough to absorb the lake’s entire volume, and as flooding displaced the air inside, geysers spouted more than 400 feet (120 m) above the ground.

Out on the lake, the effect was of a plug suddenly pulled from the drain of a bathtub; the resulting vortex sucked the drilling platform and 11 barges deep into the Earth. Meanwhile, water dissolved the pillars of salt that had held up the mine’s roof, leading to widespread cave-ins. The bottom of the lake subsided far beneath its previous level, as did much of the surrounding land. Collapsing ground caused major damage to residential homes and to the botanical gardens on the southern shore.

The sudden draining of Lake Peigneur did not end with a dry lake bed. It was still connected to Vermilion Bay, by way of the Delcambre Canal, and nature abhors a vacuum—so as fresh water poured into the mine, salt water from the Gulf arrived to replace it. The canal reversed course, briefly creating the tallest waterfall in Louisiana. Nine of the sunken barges popped back up to the surface as the lake filled up again, but the drilling equipment remained unaccounted for, lost somewhere in the vastness of the now-flooded salt mine.

Investigation

Quick to the scene was the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), part of the U.S. Department of Labor. Once the situation had stabilized somewhat, and the safety of workers and nearby civilians had been ensured, the agency began a thorough investigation into the cause of the accident. Who was at fault—Diamond Crystal, or the oil company?

Previous assessments had raised concerns about the stability of the mined-out salt dome; it may well have been a disaster waiting to happen. At the same time, the timing of the event, the location of the oil rig, and several firsthand accounts all pointed to Texaco—its exploratory drilling had either penetrated the roof of the mine, or come close enough for water to have dissolved the rest of the way through. Were the Texaco contractors in the wrong place, or had the Diamond Crystal salt mine inaccurately reported the location of its tunnels? We will never learn the answer for sure. All of the documentation was lost with the drilling platform, and it was impossible for the MSHA to pin the blame fully on either party.

Aftermath

Despite the inconclusive investigation, Texaco and its contractor ended up paying damages in an out-of-court settlement. $32 million went to Diamond Crystal, and another $12.8 million to Live Oak Gardens, the botanical garden that had ended up largely sinking into the lake. All told, this was an expensive fiasco, a huge headache to everyone involved—but aside from the reported deaths of three dogs, it was thankfully without loss of life.

Lake Peigneur is a pleasant spot these days, surrounded by trees and frequented by the wildlife of Louisiana’s Gulf Coast. Looking at it, you wouldn’t immediately know that it is much larger and deeper than it once was, or that it used to hold fresh water, not salt. The landscape has been transformed, all the same. Its calamitous history testifies to the chaos that one simple mistake can unleash.