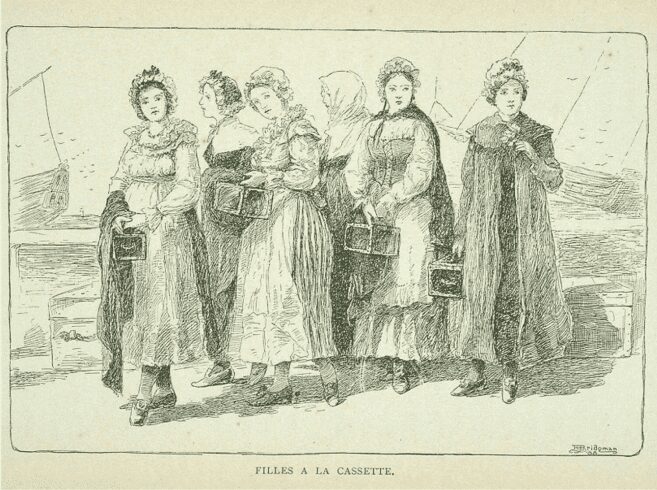

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the French king sent young women from France to their American colonies, such as Québec and New Orleans. These girls were sent as wives for the colonists to help establish the French Catholic way of life. They were known by various names and commonly called comfort girls, but one group of these women that arrived in New Orleans in 1728 gained a different name: the Casket Girls.

According to legend, these were not innocent young women at all, but vampire smugglers, or even vampires themselves.

French colony troubles

The early days for French colonists in the Americas—Québec, the West Indies, and Louisiana specifically—were tough. The settlers were primarily men working challenging manual jobs in a harsh and inhospitable environment. Women, let alone marriageable women, were few and far between.

This was a cause of great concern for the local Catholic priests, who worried about the morality of the men now chasing Indian girls for companionship. They were also concerned about establishing the Catholic faith in the new world, based firmly on the sanctity of marriage.

Young women arriving in the French Colonies

Concerned by the lack of appropriate women (which meant Catholic virgins), at various times in the 17th and 18th centuries, the leaders and priests in the new world wrote to the king of France. They asked him to send virtuous women of marriageable age to the colonies. The French government was happy to oblige.

While some women who arrived were of virtuous morals and thrived as Catholic wives, others seemed to have had more questionable backgrounds.

Several consignments of women were sent from France to the colonies in the New World over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries.

King Louis sends the Filles du Roi

The practice began in 1663 when the leaders of the French colony in modern-day Quebec petitioned the French crown for marriageable women. Over ten years, around 800 French women were sent.

King Louis XIV took the recruitment of these women seriously. He ordered one of his bishops to find appropriate girls of marriageable age, who were 12-25 years old at the time. Each girl needed a letter of recommendation from her Parish priests to be considered eligible.

These women became known as the Filles du Roi, the Daughters of the King, and most thrived as wives in Quebec. Most French descendants of the region today can trace their ancestry back to these brave young women. They spent months at sea to land in a new world and marry colonists they had never met. They would have to learn to live in harsh and “uncivilized” conditions, probably going through harrowing childbirth experiences, though fortunately, the chainsaw hadn’t been invented as a birthing tool yet.

The arrival of the Pelican Girls

The French living in the Louisiana colony followed the Canadian example in the early 18th century, seeking suitable wives for their male colonists.

The first group arrived in 1704 on a ship called le Pelican, which sailed up the Gulf Coast and docked on Dauphin Island. The girls were then ferried over to Fort Louis of Mobile. They became known as the Pelican Girls. These French women were as carefully selected as those previously sent to New France (Canada) but arrived in much smaller numbers, only around two dozen. They were cared for by a group of nuns called the Sisters of Charity, and four priests were sent with them to ensure their continued virtue.

The Pelican Girls, aged between 14 and 19, were allowed to choose a man to be their husband. But many soon found themselves dissatisfied with their new husbands, who preferred to live in the woods and were in no hurry to build proper homes for their new families. The girls staged what is now known as the Petticoat Revolution, refusing to sleep with their husbands until proper homes were provided. The French settlers came around quickly, but the girls also earned a reputation for being troublemakers.

The not-so-Pelican girls

Following the success of this mission, Louisiana made another request. Another consignment of women arrived at Biloxi in 1719. But the French government seems to have exhausted its supply of virtuous young women. Instead, women were recruited from the French houses of corrections and the poor houses. Consequently, most women who arrived at this time were poor and had a history of working as prostitutes.

While many men refused to marry these mail-order brides, the recently arrived women thrived in the Louisiana colony’s relatively debauched environment. Many migrated to New Orleans as it grew in importance in the region.

Girls of similar origins were also sent to the French colonies in the West Indies at this time, causing the local authorities to make various complaints to the French crown.

But, despite the apparent failure of these missions, it was not long before more women were requested from France. Another group arrived in New Orleans in 1728; the Casket Girls.

Here come the Casket Girls

French officials seem to have realized their error in sending prostitutes and ex-cons to the French colonies. For the new consignment destined for New Orleans, the French government again tried to recruit virtuous young women who they believed would make excellent wives.

However, finding appropriate young women was not easy. Few wanted to leave behind their families and all they knew for a perilous five-month sea voyage to marry a man they had never met. Young brides were, therefore, principally recruited from convents and orphanages. While they indeed were virtuous virgins because of this, they were also the poorest of the poor. Some were not even yet of marriageable age when they set out on their journey.

Each woman brought a trunk with their possessions, but it had to be small enough for them to carry on their own. Surviving examples of these travel caskets show they looked like tiny coffins, measuring 9 1/2 inches tall, 22 1/2 inches long, and 10 inches wide.

These were once called a cassette in French, but this evolved into casquette and was eventually Anglicized to casket, giving the group their name.

The young women traveled from their homes to the French port cities, where they boarded ships for a long sea journey. Their ships stopped in Haiti to resupply before arriving in New Orleans more than five months after their initial departure.

Why were they thought to be young vampires?

The French colonists inhabiting New Orleans likely had mixed expectations of the new arrivals. Those who remembered the arrival of the last group only a few years earlier may have anticipated similarly unsuitable women. Those waiting for wives may have hoped for a group of beautiful young girls to wash up on their distant shore.

When the Casket Girls arrived in New Orleans, many commented they were extremely pale. The colonists would have become accustomed to skin tanned by the sub-tropical sun, but the girls were in sharp contrast to this, possibly from spending months below deck on the ships. Already poor, most probably arrived malnourished and sickly, and many reportedly caught yellow fever during their stopover in Haiti.

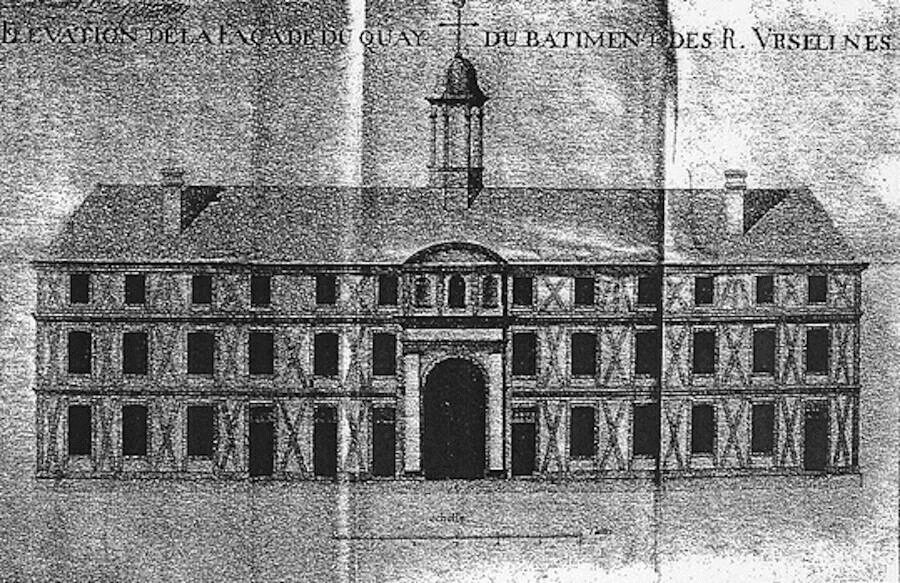

Shortly after their arrival, the Casket Girls were taken to an Ursuline convent, where they were cared for and groomed for marriage to the French settlers. The youngest may have spent considerable time in the convent waiting to reach marriageable age.

It is unclear whether the Ursuline nuns spared the girls courting traditions such as bundling when matching them up with their New Orleans husbands.

The stories’ prevalence at the time is ambiguous, but later accounts suggest that the local men of colonial Louisiana may have thought there was something strange about the young girls.

In addition to their sickly and pale appearance, they were rarely seen outside the convent. Also, around the time of their arrival, there were many deaths in New Orleans from diseases such as yellow fever, caused by the swampy conditions. Seeing bodies washing up in the Mississippi River was almost a daily occurrence.

Some colonists may have suspected that the women, who were hidden away from the community by the Ursuline nuns, had something to do with these happenings.

How the Casket Girls helped spread vampire tales

Whether stories of vampires spread in the first half of the 18th century is uncertain, but the Casket Girls are now connected with the arrival of vampire lore in New Orleans. Some suggest that the girls transported their vampire masters in the caskets that they traveled with, and others that these caskets were for the girls, who were themselves vampires. This, of course, overlooks the tiny size of the caskets carried by the young women.

Nevertheless, ghost stories surround the old Ursuline convent in the French Quarter where the girls lived, even though the convent was reconstructed in the 1750s. By then, all the Casket Girls would have left the premises.

Street historians will still say that the girls were kept locked up in the third-floor space by the nuns, who grew suspicious of the girls when they discovered that their caskets were empty. It is possible that the caskets were “empty” simply because the poor girls had very few possessions.

According to legend, the nuns sealed the shutters on the third floor with nails blessed by the Pope himself to contain this horror. They are apparently still nailed shut today, to keep undead from roaming the streets. However, the modern curators of the convent will tell you that the third floor is used for archival storage.

Local legend spinners may also tell you of two men interested in paranormal activity who camped outside the convent in 1978. Apparently, their bodies were found ripped apart and drained of blood the next day. However, if you look through local police reports, you won’t find any records of these deaths.

Were the Casket Girls involved in dark crimes?

Stories of dark crimes surround the Casket Girls, but in reality, they were not the perpetrators. These young girls were ripped away from their families and sent to the other side of the world, where they were forced into what may have been, in some cases, unwanted marriages.

We know of at least one case in Québec, where a girl was abandoned by her husband. He returned to France and left her in Canada to care for their two children. She was forced into prostitution, a crime of which she was eventually convicted despite having few other options for survival.

Perhaps more focus should be given to the forced migration and marriage of young girls at the hands of the Catholic church and French authorities.

But at the same time, the contribution of these women in establishing colonies like New Orleans through population growth and the transfer of French culture should not be overlooked. Many people, such as Madonna, Tom Berenger, and Angelina Jolie, are proud to trace their ancestry to the women of the Filles du Roi or the Casket Girls.