They talk of the Canadian North—European writers do, and oblivious, benighted people—as a bare, vacant place, devoid of history as much as it is of life. “Its emptiness, its vacancy—it’s all meaningless when viewed in a Native light,” replies defiantly Booker prize-winning author Margaret Atwood, in Strange Things, an enjoyable collection of her four 1991 Oxford lectures on the imaginative mystique of this mysterious region. Just after, she writes:

For Indigenous peoples, the wilderness was never empty but full—and one of the things it was full of was monsters. The west coast forests are prowled, not only by the well-known Sasquatch, or Bigfoot, but by the Hamatsa and the Tsonoqua, to name just three. And in the eastern woodlands, there was an even more fearsome creature: the many-faceted wendigo.

But what is a wendigo? What is the origin of this creature, and why has it been such a pervasive part of Native American lore for so long? How did it manage to infiltrate the collective imagination of so many Indigenous cultures, as well as popular fiction and Hollywood blockbusters? The answers tell a tale of careless colonialism and casual cultural appropriation, of blood, hunger, and greed, they tell a story of relentless survival in unforgiving conditions.

And they may surprise you.

What is a wendigo (1): prevalence and etymology

In 1772, at Fort Severn in Ontario, a group of Cree Indians murdered a deranged member of their family, after he had eaten the face off of a fellow human being. It wasn’t his first offense of the kind: he had practiced famine cannibalism several times before, and had actually been in home confinement before this last transgression. The strange part is that the executioners didn’t feel safe even after the death of the miscreant. “Their superstition is such,” says a contemporary Jesuit account, “that it leads them so far as to imagine that people deprived of reason can stalk about after death, and prey upon human flesh—such, they say, are wīhtikows (i.e. devils).”

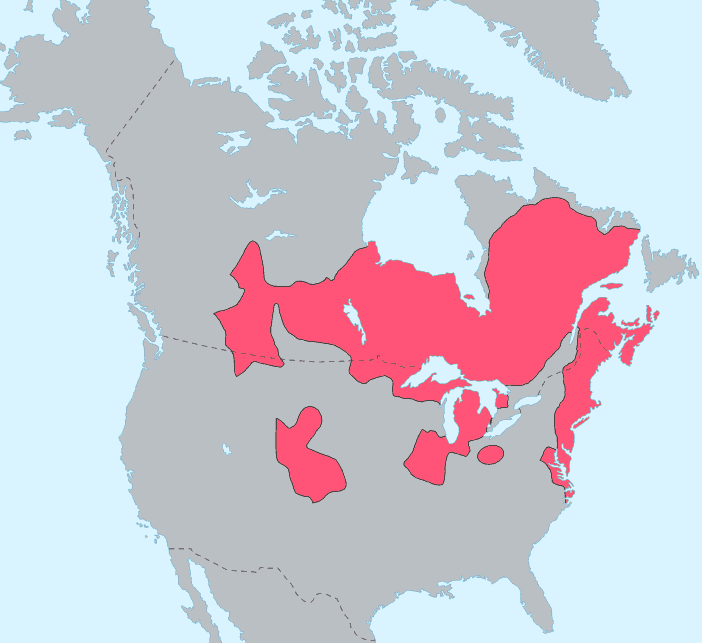

This is one of the earliest unequivocal references in recorded history to the belief in wīhtikows, or windigos, which are only two of the 40 or so three-syllable name variations (all beginning with W) Algonquian-speaking peoples such as the Cree use to describe an evil spirit-monster, able to take possession of a human being and cause them to exhibit abnormal cravings for human flesh. The word most commonly used in the English language, wendigo, is of Ojibwe origin, but it is a slight corruption of the more French-sounding windigo, which is how both English and French traders called the creature throughout most of the 19th and 20th century, undoubtedly inspired by the Ojibwe pronunciation of the word: wiindigoo.

The etymology of the word is a bit unclear, but there are several theories regarding its lineage. The most popular theory suggests that the word is derived from the Proto-Algonquian wétikowatisewin which denotes “diabolical wickedness” or “cannibal monster.” Another theory proposes that windigo may have originally been the proper name for a culture hero-trickster, before acquiring the meaning of “fool” or “madman” by way of folk etymology. However, writing in the Ethnohistory journal in 1988, Robert A. Brightman claims that these are all probably semantic innovations, and that the term windigo must derive etymologically from the word *wi·nteko·wa, meaning “owl.” It makes sense: owls, too, are omens of death, fearsome nocturnal predators with glisteningly haunting eyes. But that’s where most similarities end.

What is a wendigo (2): appearance and characteristics

Truth be told, there are almost as many variations on the wendigo’s appearance and traits as there are versions of the word itself. In most of these variants, however, the wendigo is said to be a giant spirit-creature of the forest, with lustrous eyes rolling in blood and merciless heart of ice. Just like an owl, it whistles, beckoning death, but it does so through blackened and raggedy lips, looking almost as if it had been gnawing on itself in hunger. And hunger—voracious hunger for human beings—is its prevailing characteristic: the wendigo is almost invariably described as a ravenous cannibal, getting hungrier the more it eats.

It usually has no gender, although most wendigos are believed to have been, at some point in the past, a man or a woman. In most stories, they have haggard, skeletal bodies, thinly veiled under an ash-colored, mummy-like skin. They also have animalistic snouts and canine teeth, as well as long tongues and bird-like claws. In some stories, they have feet of fire, whereas in others they leave trails of giant footprints in the snow, as if from gargantuan snowshoes. Either way, they are incredibly fast, able to travel with the speed of the wind, and they can appear and disappear in a moment’s notice. “You cannot outrun or outwit a wendigo,” warns Atwood. “Most of the time, you can’t even converse with one, because the wendigo has lost its capacity for human speech.”

One particularly bloodcurdling description of the wendigo comes from the Ojibwe scholar Basil Johnson, who writes, in his 1999 work, The Manitous, the following:

The wendigo was gaunt to the point of emaciation, its desiccated skin pulled tightly over its bones. With its bones pushing out against its skin, its complexion the ash-gray of death, and its eyes pushed back deep into their sockets, the wendigo looked like a gaunt skeleton recently disinterred from the grave. What lips it had were tattered and bloody. Unclean and suffering from suppuration of the flesh, the wendigo gave off a strange and eerie odor of decay and decomposition, of death and corruption.

What is a wendigo (3): etiology and consequences

That Cree family we mentioned, the one who killed one of its own in 1772 Ontario for fear he had turned into a wendigo, had all the right to dread revenge: wendigos are quite difficult to do away with. That’s because they aren’t just something out there—they are also something within. Indeed, wendigos are much more spirits than monsters, the restless spirits of people who have been corrupted by insatiable greed, who have succumbed to the temptation of human flesh, and who are now doomed to seek out others to feed upon. Once they have taken over a person, they can consume them from the inside, leaving them hollow and soulless, with an unhallowed hunger that can never be satisfied.

Hence, as Atwood remarks, being eaten by a wendigo is only a slight problem—becoming one is what’s really frightening! Because, “if you go wendigo, you may end by losing your human mind and personality, and destroying your own family members, or those you love most.” It’s likely that nobody in that Cree family feared for their own lives in 1772: they were all afraid for the lives of the others, the lives of their loved ones. The wendigo legend, in other words, was never really just another monster story about a particular evil demon à la the Navajo skinwalker or Hollywood slasher villains; it was, from its very beginnings, a paean to the human collective, a cautionary tale about the need to protect one’s tribe from the evil that lurks inside it, the evil of individual greed and selfishness.

There are several ways in which an ordinary person may be transformed into a murderous wendigo. In Dangerous Spirits, historian Shawn Smallman infers the following five: starvation, freezing to death, a shaman’s curse, spiritual corruption, or bad dreams. It’s obvious the former two are related, as are the last three. For such reasons, wendigos are often perceived as symbolical personifications of three common threats to human survival in the Canadian wilderness: winter, hunger, and selfishness. Atwood makes the necessary connection between the three: “winter is a time of scarcity, which gives rise to hunger, which gives rise to selfishness.”

Since only the last of the three is within the realm of human control, it’s usually thought of as the greatest threat, if not the only real one. Indeed, self-interest is often seen as the root cause of most wendigo transformations, whether in myth or in literature. In this light, cannibalism is merely a superficial consequence of selfishness, its metaphorical upshot, a symptom of the individual’s deep-seated corruption and hunger for power. Or, is it?

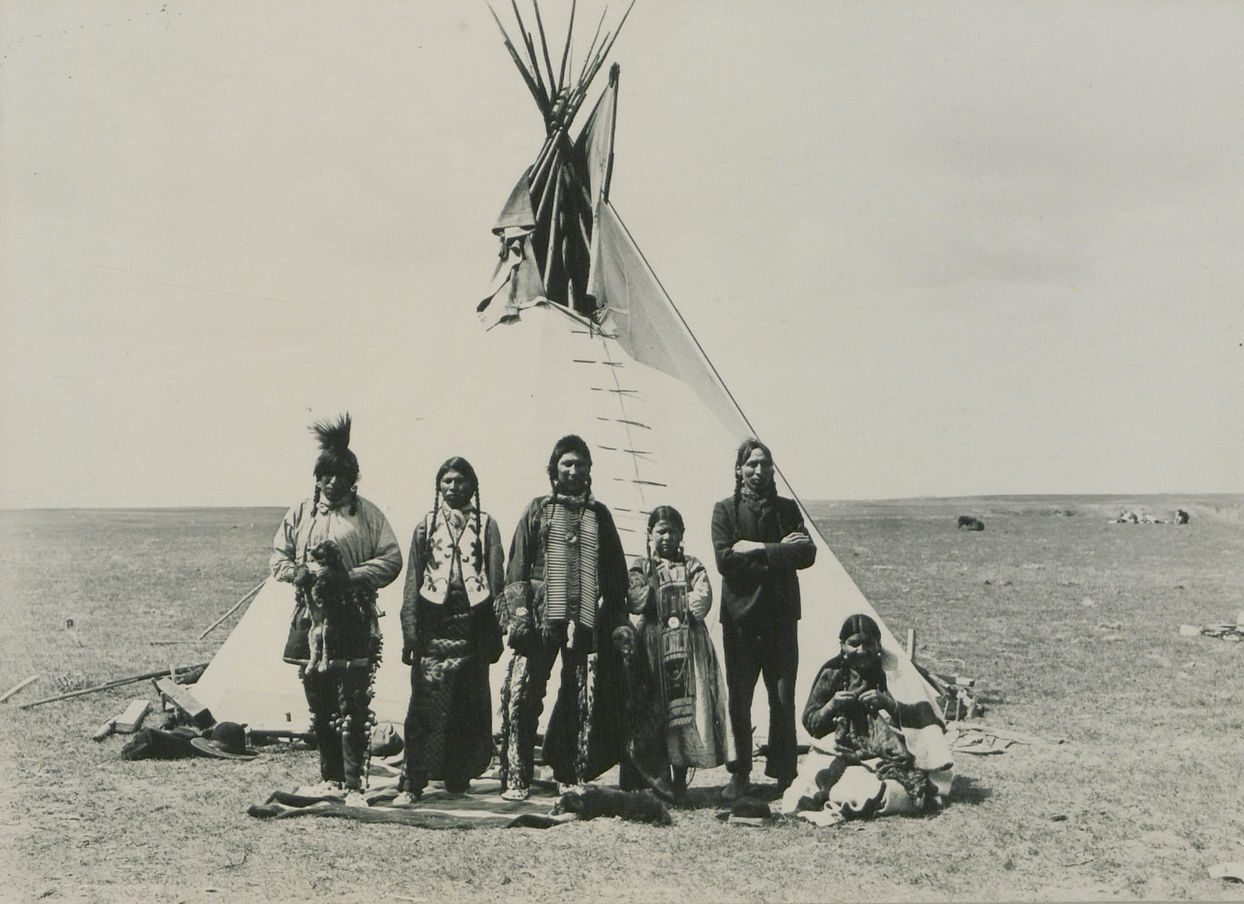

The story of Swift Feet, a real-life wendigo monster

During the fall of 1878, a Plains Cree trapper named Kakisikuchin, and known in English as Swift Runner, separated from his father-in-law and headed to the west bank of the Sturgeon River in Alberta, northeast of Fort Edmonton. There, just before the bitter winter freeze, he set up two camps, for himself and for his extended family—his mother, brother, wife, and six children. Several months later, as the 1879 spring thaw began, Swift Runner suddenly turned up at the Catholic Mission in St. Albert, alone and visibly shaken, with the news that his entire family had perished during the harsh, gameless winter. Some of them starved to death, he told the priests at the mission, and some of them dispersed in search of food; the rest, he claimed, committed suicide, out of desperation and hopelessness.

Naturally, the priests were horrified to hear such a story but were also quite suspicious of its veracity. For one, weighing at about 200 pounds (90 kg), Swift Runner didn’t look as malnourished as one would expect from a starving man. The fact that his winter camps were located no more than 25 miles (40 km) from a known Hudson’s Bay Company post—and its emergency food supplies—further cast doubt on his story. And then, there were also the night screams. For a few days, Swift Runner couldn’t bat an eyelid without waking up the entire congregation with his howls of terror. “What is it?” one of the priests eventually asked him. “It’s the wendigo,” he replied. “I’m haunted.”

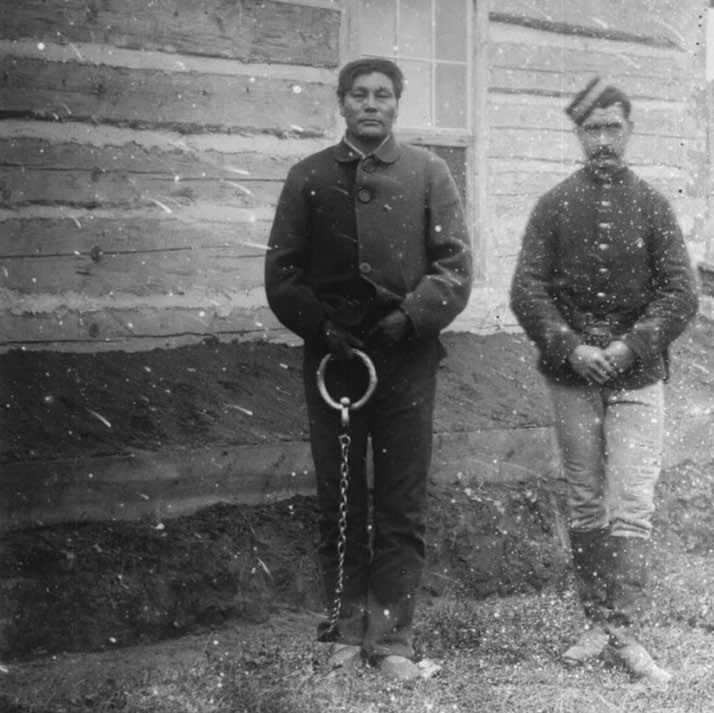

The priest, one Hippolyte Leduc, immediately contacted the Mounted Police, who sent Inspector Severe Gagnon to the top of what is now St. Albert’s Mission Hill. Soon after, Gagnon took Swift Runner to the location of his family’s winter camps. There, he was met with a most gruesome sight: the skeletal remains of several bodies, scattered across the landscape, some of them partially eaten away and others showing deep, gaping wounds, their limbs contorted in the terror and agony of their last moments. It wasn’t long before Swift Runner confessed to killing and eating six members of his family. The only two he knew nothing about were his mother and brother: both of them had left the group earlier in the winter.

The reconstruction of the events which transpired that shivery, dreadful winter of 1878 was later painstakingly pieced together by Gagnon, with the obliging help of Swift Feet. It all started, Swift Runner said, when his eldest son had died of starvation at the first camp, and was properly buried; indeed, his emaciated corpse was later recovered by the police, unspoiled and well preserved. What followed next can only be described as strange and shocking. Possibly fearing a similar fate—or perhaps possessed by some unknown force—Swift Runner headed resolutely to the second camp, where he cold-bloodedly killed his wife and his next eldest son. Then, he had one son kill the other, then killed the survivor, after which he hung his youngest, a baby, from a tent pole. And then—oh, then—he began eating the remnants, limb by limb, finger by finger, getting hungrier with every new bite, until all that was left was just a pile of bones.

Wendigo psychosis: when science becomes (stranger than) fiction

Swift Runner was eventually charged with the murder of his family. He was convicted and hanged by Euro-Canadian authorities at Fort Saskatchewan, near the end of 1879, on a cold December day, possibly not that different from the one that started it all. “I am the least of men and do not merit even being called a man,” he told Father Leduc, moments before the trap door swung open. To any Cree present, that sentence meant something more than just remorse—it meant a plea for understanding, a plea that Swift Runner’s actions were not the result of a conscious decision, but rather a spiritual curse. He was, simply put, possessed, and thereby “had no alternative course of action.”

“The wendigo made him do it,” Algonquian tribes might say, writhing in fear from the creature’s return. For they believe it has come back, the wendigo, hundreds of times in the past, and is wont to return again, to haunt the north and the people who live there. In an attempt to explain away this fear—as well as cases such as that of Swift Runner—early 20th-century psychiatrists coined the term “wendigo psychosis.” One of the earliest mentions of the phrase (or at least a similar one) can be traced back to John Montgomery Cooper, an American Catholic priest and anthropologist who wrote, in an overtly racist 1933 article titled “The Cree Witiko Psychosis,” the following:

A very typical psychosis occurring among the eastern Cree and some other northern Canadian tribes is the “Witiko malady.” This particular form of mental disturbance is characterized by (1) a craving for human flesh, and (2) a delusion of transformation into a Witiko who has a heart of ice or who vomits ice.

About three decades later, in Windigo Psychosis, perhaps the most influential work on the subject, Morton I. Teicher argued that wendigo psychosis was a real psychological disorder, unique to the Indigenous people of Canada and the northern United States, the outstanding symptom of which was “the intense, compulsive desire to eat human flesh.” Explained Teicher further, “The individual who becomes a windigo is usually convinced that he has been possessed by the spirit of the windigo monster. He therefore believes that he has lost permanent control over his own actions and that the only possible solution is death. He will frequently plead for his own destruction and interpose no objection to his execution.”

“He who fights with monsters should see to it that he himself does not become a monster”

Teicher’s landmark study led to a widespread recognition of wendigo psychosis as a legitimate, culture-bound psychiatric disorder. Throughout the decades that followed, a host of researchers expanded upon his findings, writing at length about the syndrome, and unearthing a case study after case study from the tattered archives of old Jesuit priests. Symptoms were catalogued, episodes of cannibalism described in detail, and various theories of causation formulated.

But then, in 1982—after having lived for five years among Northern Algonquians—cultural anthropologist Lou Marano published a seminal study on the subject, in which he argued that there was “no reliable evidence for psychotic cannibalism” in the entirety of wendigo literature, and that the very idea of the disorder was “an artifact of prejudiced research,” such that purposefully failed to distinguish between tales of real-world cannibalism in regions of scarcity, and the supernatural beliefs of the people living there.

The paper caused a considerable stir, leading many to question the legitimacy of wendigo psychosis. In the years that followed, more and more research emerged that further challenged the idea of the disorder, while also exploring the cultural significance of wendigo tales, and how they were used to establish and reinforce social and religious norms. In a dramatic twist, the wendigo diagnosis itself became diagnosed as a reflection of Western cultural imperialism, and a concept used to impose Western values on Indigenous populations.

Europeans, it was now argued, were always much less interested in understanding the supposed “disorder” than they were in using it as an excuse for capitalist expansion. As a result—as Kevin J. Wetmore Jr. concludes in Eaters of the Dead—the wendigo stopped being just an evil, Indigenous spirit of starvation and cannibalism; it became another name for the Jesuit missionaries, the pilgrims, the fur traders, the explorers, the psychologists, and all the other Europeans who came to the New World. They were the real wendigos all along, for they did what all wendigos tend to do: they consumed the lives of others for their own private purposes and profits.

The subsequent metamorphoses of the wendigo legend

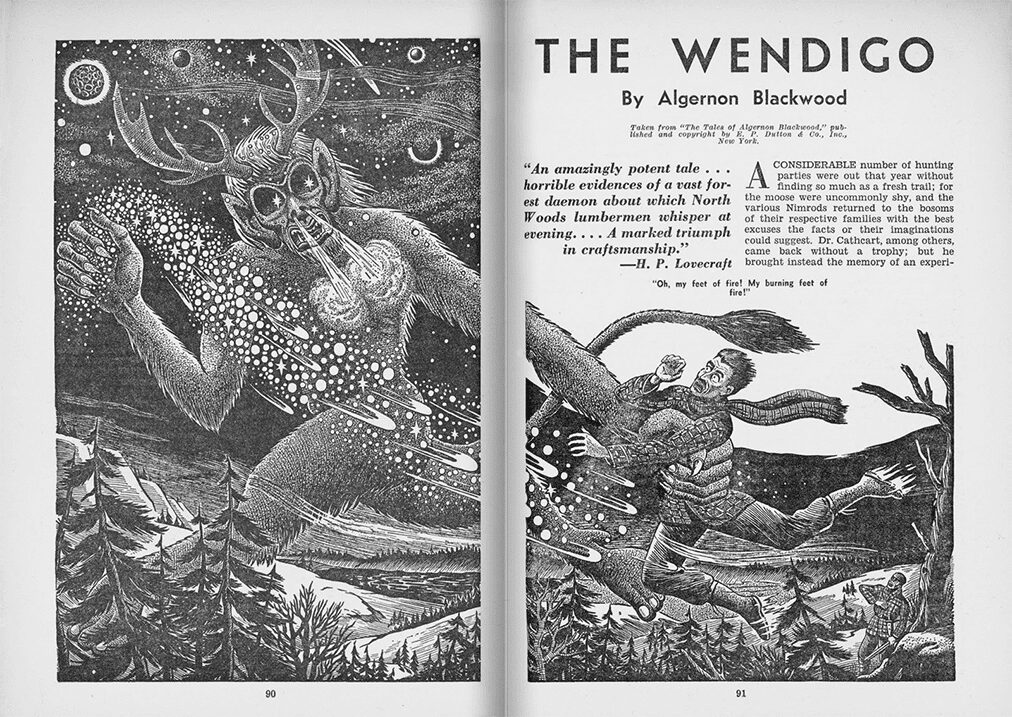

With the case of Swift Runner being the only documented case of wendigo-inspired cannibalism, wendigo psychosis is generally no longer considered a legitimate psychiatric disorder. But the fascination with the creature still looms large in certain Indigenous communities—as well as in Western pop culture. Ever since master-horror author Algernon Blackwood made the wendigo famous in his eponymous 1910 novella, the creature has been featured in countless works of fiction, most famously perhaps in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary and its two movie adaptations. It has also been the subject of several other horror movies, such as the underrated Ravenous (1999) and the well-received Antlers (2021), as well as TV shows like Supernatural and Hannibal. Less conspicuously, it’s been the inspiration of the White Walkers from Game of Thrones—they too are gaunt giants from the north, with hearts of ice and an ability to reanimate the dead.

But almost all of these portrayals fail to capture the essence—or even the original traits—of the wendigo monster. In Blackwood’s story, for example, the wendigo is completely stripped of its cannibalism and is described as “simply the Call of the Wild personified.” In Pet Sematary, King describes it as “a beast looking like a lizard born of a woman,” with “cracked reptilian yellow skin” and “massive curling horns” instead of ears. This description set the tone for later portrayals of the wendigo, which soon superseded the ones prevalent among the Algonquian people. Especially that last feature, the curling horns or antlers, have become an iconic attribute of the Hollywoodized wendigo and are rarely omitted in modern depictions, despite not being present in the original myth.

A scene from Antonia Bird’s Ravenous (1999)

In many ways, the price of the wendigo becoming a globally recognized symbol has been its metamorphosis into something other than itself: a less complex (and more generic) antler-bearing wood monster. Yet, the Algonquian version is still the scarier one, as it is less about what the other can do to me and more about what I can do to the other. Fortunately, this version survives still, if merely in the nightmares of the few remaining Algonquian storytellers and the works of Indigenous authors and directors where—as Shawn Smallman demonstrates—it remains one of the most powerful metaphors for excess, and a potent trope to comprehend and critique colonialism. But it’s even more than that: a lasting symbol of the dangers of individualism, a cautionary tale on greed, gluttony and selfishness, and a terrifying warning to all who would succumb to these base desires.