Consisting of approximately a 10% solution of opium powder mixed with alcohol (and sometimes, spices and honey to mask its bitter taste), laudanum was a unique medicine that rose to prominence within the nineteenth century. Used for chronic conditions such as asthma and headaches, right through to menstrual cramps and even teething infants, this strong concoction was prescribed for a myriad of aches and pains and marketed accordingly as a ‘cure all’ solution. Laudanum was typically packaged in a glass bottle and taken in drops whereby the amount was dependent on both the strength of tincture and severity of the symptoms, However, whilst it’s pain-relieving properties were unrivalled by any contemporary medicines, laudanum was also highly addictive and created a culture of addiction in Victorian society where increasing doses were required to obtain the initial effects felt.

Recognisable by its reddish-brown appearance and strong scent, opium is a drug derived from the juices of the opium poppy, in which its uses were known about as far back as antiquity. In the 16th century, the Swiss-German alchemist, Paracelsus, concocted a pill he called his ‘laudanum’ (derived from the Latin word, laudare, “to praise”) made from many expensive materials that included crushed pearls and gold, but most effective due to only one ingredient – namely, opium.

The advent of laudanum

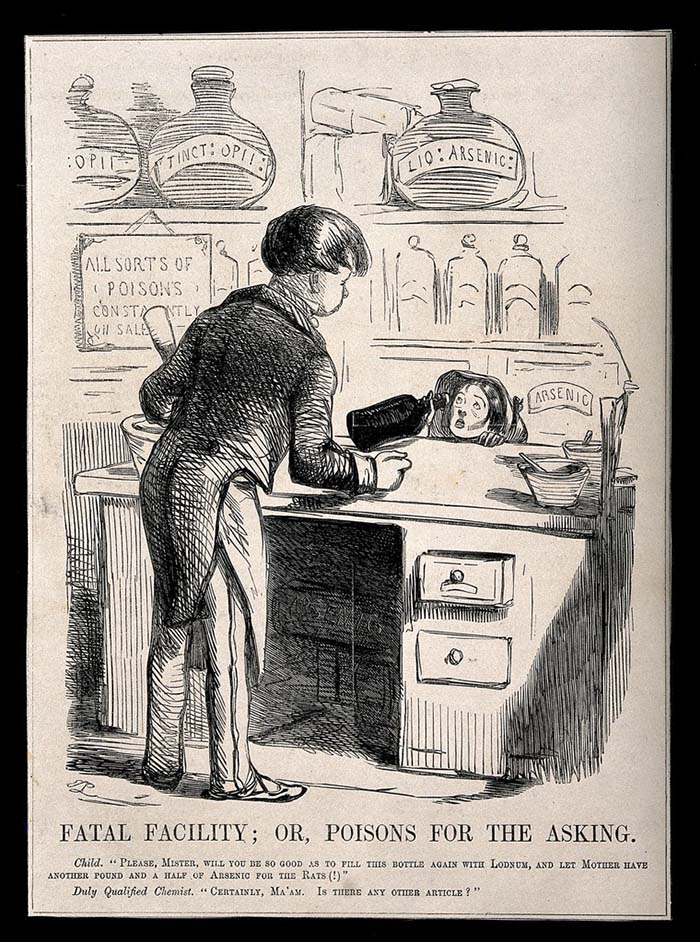

By the 17th century, the physician Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) laid the foundations of laudanum’s success through simplification of its recipe to just opium alcohol. In the eighteenth century, opium and laudanum were well renowned and their popularity reflected in contemporary culture, such as the above engraving by the satirical artist William Hogarth (1697 – 1764). By this point, laudanum had ceased to be a particular or specific mixture of ingredients, with the term now referring to any mixture of opium and alcohol. This enabled the mass production of the medicine in a free-trade market that was for a long time unregulated. Laudanum subsequently became highly sought after for not just its pain-relief, but also the euphoric effect that it induced and was readily available from pharmacies, tobacconists, barbers and even confectionaries.

An anaesthetised age

Easily accessible and inexpensive, by the mid nineteenth century laudanum was cheaper than alcohol and thoroughly ingrained within the fabric of Victorian life. The nineteenth century became what medical historian Roy Porter (1946 – 2002) described as an “anaesthetised age – precisely because of the startling surge in the use of powerful narcotics, drawing upon alcohol and opium”. Although its withdrawal symptoms are unpleasant – which include tremors, sweats and nausea – the addictive properties of the drug were not fully realised or understood until the twentieth century. It thus remained a highly popular “medicine” used by all classes of society, including a selection of famous literary figures. The English essayist, Thomas de Quincey (1785 – 1859), for example, was best known for his publication Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1821) which charted his difficult relationship with the drug, having become dependent on after using it to manage the crippling pain caused by his Trigeminal Neuralgia.

Romantic poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806 – 1861) too, struggled with the addictive properties of opium having been prescribed it as a fifteen-year-old to treat the pain resulting from a spinal injury. Browning continued to take the solution well into adulthood, and reportedly used to take approximately 40 drops a day – a high dosage even for an accustomed addict.

Another figure who supposedly suffered the consequences of over-using laudanum included the artist, poet, and artist model Elizabeth Siddal (1829-1862). Siddal is recorded as having had fragile health for the majority of her life but was given laudanum initially in 1852 for suspected pneumonia caused by lying in cold water whilst posing for a painting by John Everett Millais (1829 – 1896). She continued to take the drug and eventually died from an overdose in 1862 after suffering from depression which was exacerbated by the death of her child. Other famous figures of the Victorian era that have fallen foul of the addictive properties of this peculiar substance included Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834), Edgar Allen Poe (1809 – 1849) and Percy Shelly(1792 – 1822) – the latter of whom allegedly took it to “dampen his nerves”.

A pre-painkiller era

However, whilst laudanum and opiates within the Victorian period have been explored retrospectively from a rather sensationalist perspective that tends to look at its addictive properties, it is also important to remember laudanum’s medical role, when it was used as a tool for pain management in sickness and end-of-life care.

In an era before the invention of aspirin, painkillers and sleeping tablets, to be in pain was a thoroughly unpleasant experience. For those suffering from a chronic or terminal illness (for example, cancer or tuberculosis) laudanum and the use of opiates provided a much needed and welcome relief. It is also equally vital to remember the context of which it was used. One of the most important aspects of Victorian medical care of the sick or dying was pain relief, and historians studying this subject have argued that medical practitioners during this period generally deployed a disciplined use of opium, that took into account patient well-being and contemporary medical laws and ethics.

The good death

The pain relief and calm state that opiates brought to a patient was also in keeping with the idea of “the good death”. The idea of ‘dying well’ is epitomised by the concept of ars moriendi (meaning, “the art of dying”). Generally, the good death was understood as one that was calm, quiet and prepared for in which the individual was not in physical or emotional pain. Given the effects that it produced and induced in its user, Laudanum could therefore help achieve this. For example, in his book Euthanasia (1887) the physician William Munk (1816 – 1898) articulated opium as an invaluable tool for both practitioner and patient, arguing that its main strengths were its ability to alleviate what he referred to as the “sinking feeling […] that dreadful distress around the heart and stomach” which thus allowed it’s sufferers to “[…]die more easily with composure”.

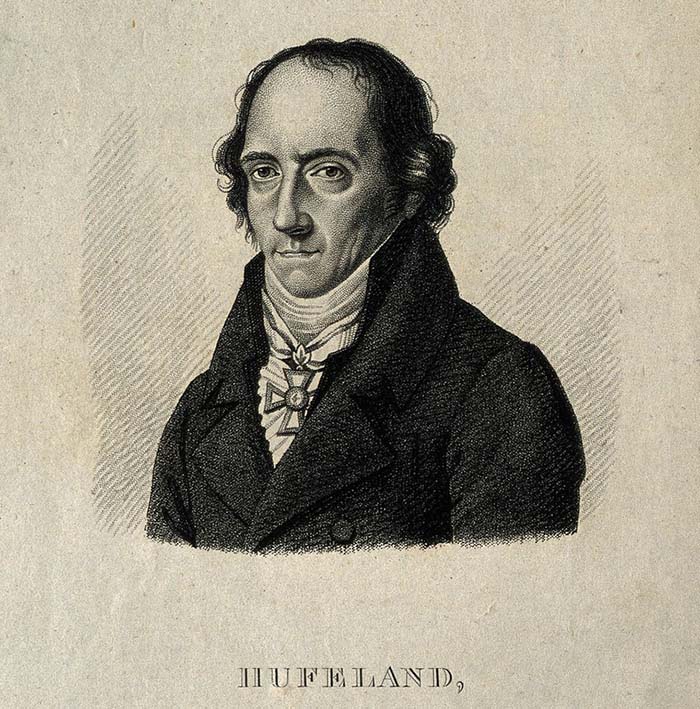

Other contemporary physicians echoed similar sentiments. In the 1830’s the influential physician, naturopath and writer, Professor C.W. Hufeland (1762 – 1836), described opium as something that “removed the pangs of death” and imparted “courage and energy for dying”. He revered the use of opium as a great and powerful medical tool, hypothetically questioning: “What would a physician be without opium in attendance on cancer or dropsy of chest? How many sick has it not been saved from despair? One of the great properties of opium is that it soothes corporeal pains and complaints – but affords also to the mind a peculiar energy, elevation and tranquillity”.

Indeed, this was true in the case of mathematician and writer, Ada Lady Lovelace (1815 -1852) who relied on laudanum to help her function whilst battling terminal uterine cancer. A year before her death, the young woman had informed her mother that whilst the pain caused by the cancer was indescribable, the maximum dose of opiates that had been administered were helping her cope physically and mentally, musing: “you think me philosophical about it; but I should not be so if I did not get free occasional intervals [free of pain]”’. The fact that opiates are addictive but can offer some respite to those in desperate need of pain-relief is a negative that medical practitioners both then and now overlooked. Modern studies have shown that opiates are very successful in controlling pain and have a positive psychological influence on those suffering, or who are at the end of their life. As a result, controlled dosages and use of opioids are still used to this date, if and when necessary. Therefore, as put forth in the book Death in the Victorian Family (1996), it can then be said that the view which 19th century medical authorities took regarding opiates and pain management, are not dissimilar to modern medical practitioners; specifically, that the danger of addiction is not of concern when a terminal disease is painful.

The fall of laudanum

By the second half of the nineteenth century, attitudes towards laudanum began to change. The invention of the hypodermic syringe had led to increased usage and doctors were growing increasingly aware of its highly addictive properties and withdrawal symptoms.

Read more: The Plague Doctor Hat and Its Secret History

This was reflected in the periods wider medical literature: for example, Eduard Levinsteins Die Morphiumsucht (1878) connected the use of opiates with a desire or craving for more in a time where the word, or notion of, addiction did not yet exist. Laudanum had also become a class issue, where concerns about its non-medical use led the upper and middle classes view the heavy use of laudanum as working-class dissipation. This led to attempts of legal regulation through the 1868 Pharmacy Act, which limited the sale of poisons and what were considered dangerous drugs to qualified druggists and pharmacists.

However, what truly hammered the final nail in the coffin of normalised opioid use was the invention and introduction of pure aspirin in 1889. From this point forth, society now had access to a safer painkiller that did not induce the same high and did not pose the same level of addiction as laudanum. Combining this advent with the growing medical concern over the use and regulation of laudanum, by the end of the nineteenth century there was a growing anti-opium movement whereby the popularity of laudanum can be seen to have fallen, just as quickly as it has risen.