Camazotz: The little known Mayan bat god

Ever decided to go swimming in one of those sacred cenotes while on holiday in Mexico? Yes? You have entered the cavernous darkness and the domain of Camazotz, the Mayan bat god who guards the entrance to their underworld.

Among the Zapotec deities in Mesoamerican mythology, he is one of the keepers of the underworld Xibalba, hidden just below the peaceful Oaxacan valley above. Quite possibly one of his bat-like monsters stares back at you as you dog-paddle in the deep.

Camazotz: The Mayan god of the Quiche tribe you might not want to meet at night

Suffice to say, you wouldn’t want to tussle with this bat god. In the Quiche language (sometimes transliterated as the K’iche language), Camazotz translates as “death bat” and is most often associated with night, death, and sacrifice. In many images, he is holding a sacrificial knife in one hand and a human heart from the victim in the other.

Camazotz: First appearance of the bat god in the Popol Vuh

The tales of the death bat are documented in the Popol Vuh. Following the historical and mythical development of the Quiche people, this sacred text warns the Mayan peoples to be cautious around these mystical places. You should, too, given Camazotz’s reputation, tenacity, and mean streak.

Read more: The Aztec Death Whistle and Its Bloodcurdling Scream

In several stories, this god and his minions guard the gateways to the underworld. An entrance to an underworld cave and limestone pool of water (a cenote) was a sacred gateway to the Zapotecas. Their waters could grant life or take it away just as quickly. Reverence to the deities, regular offers, and prayer to the keepers of the caves were the only proven ways to keep these forces at bay.

Camazotz: The Death Bat Meets the Hero Twins

Camazotz’s first tale in the sacred writings of the Popol Vuh covers the creation story of humankind. It begins with the gods attempting to create the perfect humans out of various materials: mud, wood, and corn. Meanwhile, two Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque, are playing Pok-ta-pok in the ball court just outside one of these cenotes.

Hunahpu and Xbalanque’s ball falls directly into the cavern, and our heroes descend into the underworld. There they are forced through every kind of trial, facing death and torture by all manner of Mayan gods, demons, and beasts of the deep.

When the hero twins arrive at one trial in the House of Bats (Zotzilaha), they meet the god Camazotz. This trial involves them surviving in the cave until sunrise when bats and other nocturnal monsters lay to rest.

They successfully hid out in their blowpipes (obviously very spacious) until shortly before dawn. When Huanahpu snuck out hiding to see if any rays of daylight were present, Camazotz didn’t hesitate and immediately cut off his head. Legend has it that the bat deity used his head to play Pok-ta-Pok with his rival gods.

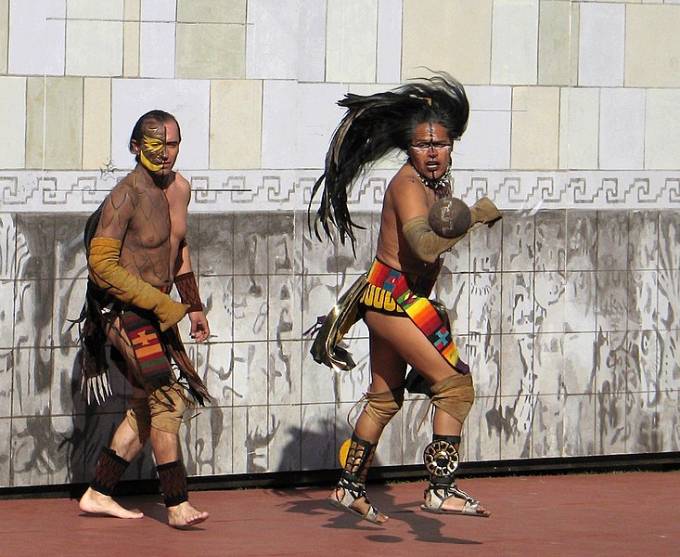

Camazotz’s courtyard: Pok-ta-Pok at Monte Albán

You can see a fully restored Pok-ta-Pok court at Monte Albán, in modern-day Oaxaca state, Mexico. The heart of the Quiche homeland is at the center of ancient Mayan civilization, where societal elites played the game.

Symbolically, the game represented the conflict between the forces of good and evil, darkness and light. So whose team was Camazotz playing for?

Camazotz: A force of pure evil or simply an omnipotent judge?

Although Camazotz was associated with death, he was just one Zapotec god directly involved in creating humanity and its eventual destruction. As one of the four animal demons, he was charged with wiping out all early humans during the first sun and age.

While there’s little doubt he usually plays the villain and relishes his part in destroying the old order, he is indirectly clearing the slate to create the perfect servants on earth. The gods are working in tandem at a common purpose.

Without darkness, there can be no light, according to the mythology which early Mesoamericans believed. It might be a stretch trying to see beyond this heart of darkness, but this shadowy figure does end up doing something good, albeit often obliquely.

Camazotz: Mankind promised fire

In this final tale, a messenger ascends from the depths of the underworld Xibalba. It is the classic form of Camazotz, with a head, pointy ears, and sharpened fangs just like a vampire bat adorned with the torso of a human.

He is willing to offer humans one of the underworld’s most powerful tools to use: fire. However, to avoid any Prometheus-like situations with humans stealing fire from any god, he has brokered a direct pact between Lord Tohil, patron god of the Zapotec tribe, and the mortals. They would receive fire in exchange for regular sacrifice and offer, specifically “the [opening] of their armpits and their waists” in human sacrifice or blood offering.

Camazotz: So was the gift to the Maya Quiche tribe a trick?

Some of the gods argued for the benefits as an aegis of good. Humans could use fire as a tool to clear land, preserve foods and continue to learn and worship into the night. Others believed it could cause harm, death and destroy entire forests, farms, villages, and towns. No wonder Camazotz favored sharing the dangers and power of fire with humanity.

Camazotz: Beyond the Popol Vuh: the literature, art and oral traditions of the Maya

There are other images and accounts beyond these three tales about Camazotz in the Popol Vuh. Many form part of the folklore and oral tradition across Central and South America. Camazotz’s image is on pottery, can be found among Zapotec hieroglyphs and other texts.

Unfortunately, only a few codexes of original glyphs have been found. Like the Popol Vuh, some of the texts have been analyzed and interpreted by academics. While perhaps not to the perfection of a native K’iche language speaker, or the understanding of Camazotz’s cult follower, we’ve moved beyond the broad-stroke interpretations of biased conquistadors.

Camazotz: Living inspirations for vampires

When Europeans, Asians, and Africans heard about real blood-sucking bats and human sacrifices in Mexico, their imaginations went wild. They produced dozens of new vampire tales inspired by travels and their own legends alike.

Who could have thought a humble cloud of circling bats could inspire such fear and artistry? From hopping vampires in China to the garlic-haters of Eastern Europe, the lore of bat-like creatures brings both fear and respect to this day. All were likely inspired by Desmodus rotundus , aka the common vampire bat, which terrified locals and newcomers alike.

Camazotz: Inspired by the ancients?

Fossil records show that the Zapotec specimens of this vampire bat have decreased in size since the Late Classic period. Scarier yet are earlier records that prove megafauna, including one giant species of vampire bat, Desmodus draculae, which grew to the size of an adult human, roamed the land 100,000 years ago, long before the history of Mayan mythology was written.

Camaztoz: His disciple the Common Vampire Bat

Although Desmodus draculae is extinct and genetics have changed the size of the modern vampire bat, Desmodus rotundus , they are still fearsome beasts to encounter either in person or in children’s bedtime stories. Both the stories and the bats are prolific. From Argentina to Northern Brazil and the Guatemalan highlands up to the border of Mexico. They were shared throughout the history of the Mayan people.

Read more: 536 AD: The Worst Year Ever

Camazotz: Not just history, his legend lives on

Some of those stories and the mythology lives on retold through oral tradition into the modern age. They range from the banal “if you wander into the woods alone at night watch our for a bat-like creature in the dark” to slightly more horrifying “if you are a naughty child … Camazotz or his minions of vampire bats will carry you away to the underworld.” Like the very nature of the bat god, however, these occasionally come with a positive twist.

Some pregnant descendants offer sacrifices to the bat gods at the entrance to their domain to ensure a healthy baby. It is interpreted as if they are entering the womb [of the earth], offering respect to the greater natural powers (rather than any creature or god) in return for this new life.

Camazotz: A Good or Evil creature?

Whether this god was pure evil, or just a more balanced arbiter of justice of the caped-crusader variety, descending from a dark tower is left to the interpretation and the imaginations of the beholder.

The lore and artwork, both ancient and contemporary, show considerable depth in the types of inspirational stories behind the myth and its oral tales. Many are horrifying, while others prove more romantic or retell of the fundamental struggles of humanity.

Camazotz: Modern art and our future understanding

Christian Pacheco recently created a Camazotz mythology-inspired Batman bust (see feature image.) It was so true to the Zapotec forms and style that many people mistook it for genuine. Although striking, it is neither of Zapotec origin nor from the Classical Era but certainly helps bring attention to his lore and mystique.

The Zapotec bat god Camazotz deserves to be recognized as one of the earliest documented bat tales in the Mayan civilization. With further archeological research, the discovery of previously unknown details, and the interpretation of other surviving texts, this is likely not the last we’ll hear of this dark knight and early winged bat crusader from the annals of history.