By the end of this year, 2023, there will be a shift in the Earth’s orbit. The change will trigger a solar storm, similar to the disruptive 1859 Carrington Event, bringing potential havoc to power grids, communications, and services, while also heightening the risk of skin cancer and other skin diseases. Complicating matters, a large country will carry out a bioweapons test, raising serious concerns about global security and potential chemical warfare.

Fast forward ten years into the future, and the polar ice caps will melt into the ocean, causing the world water levels to rise. Coupled with a worldwide nuclear conflict, this will render the Northern Hemisphere nearly uninhabitable. Europe will then be reclaimed by Muslims, who will hold sway over the continent for decades. But then, in 2066, powers will shift again, as the US will employ a new climate-changing weapon to target Muslim-controlled Rome.

In the year 2100, a new energy source, in the form of a man-made sun, will not only illuminate the dark side of our planet but also humanity’s path forward. However, a mishap on its surface, two centuries later, will trigger a severe and life-threatening drought. Fortunately, humanity will have colonized parts of our Solar System by then, even harnessing nuclear power on Mars. As resources on the Earth dwindle, Mars will seek independence, igniting an interplanetary conflict. By the 3800s, this war will nearly obliterate all life on our planet, necessitating a new prophet to lead a resurgence of morality among the surviving humans, creating a new religion, a religion of hope and progress…

Consider it outlandish, consider it farfetched, but this will all inevitably happen. So said Baba Vanga, a blind Bulgarian mystic of Macedonian heritage, semiliterate in Serbian Braille only, but somehow still able to converse both with the dead and the Communist secret services of her country. How she, an uneducated peasant from a small village, became the world’s most celebrated 20th-century clairvoyant is as much a story of superstition and myth as it is a story of history, nation-building, and perverse Cold War politics.

1911: Baba Vanga’s birth (or, what’s in a name?)

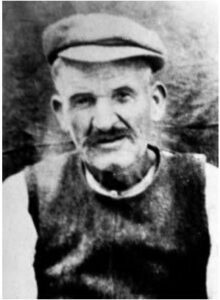

Baba Vanga (meaning “Grandma Vanga”) was born a frail, premature baby, on January 31, 1911, in Strumica, present-day Republic of North Macedonia, to a small family of impoverished farmers, Pande and Paraskeva Surchev.

Following an old Slavic custom, Vanga’s name was decided by asking the first person her parents met on the street right after she was born. Yet, the initial suggestion, Andromache, didn’t find favor with her grandmother (it sounded “too Greek” to her, during a period of anti-Hellenic sentiment among the Balkan Slavs), so after seeking advice from another passerby, the young girl was christened Vangelia.

Somewhat ironically, the name is a minor Slavic adaptation of the Greek Ευαγγελία, which signifies “good news.” Latinized as evangelium, the word was used in the Vulgate—the first Latin translation of the Bible—to refer to the Gospel message. In fact, the word “gospel” is an Old English translation of Baba Vanga’s birth name: gōdspel (gōd “good” + spel “news”).

A historical interlude: glimpsing into 20th-century Balkans chaos

When Baba Vanga was born, Strumica was still a part of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. As she began uttering her first words, the Balkan Wars erupted, putting an end to the Empire, and sparking swift shifts in territorial control. When the Wars concluded, in the summer of 1913, Strumica became part of Southern Serbia (later Vardar Banovina), the newest part of the now considerably expanded Kingdom of Serbia.

As the curtains fell on World War I in December 1918, the Kingdom of Serbia became an integral component of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, which was renamed the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929. Just 12 years later, in the spring of 1941, the country effectively ceased to exist, as it was occupied and divided by the Axis powers, only to reemerge as the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) in 1945, following the close of World War II.

In the context of the SFRY, a one-party federation of six republics and two regions, Strumica was situated as city in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, the first internationally recognized state for the Macedonians. Alongside Petrich, a Bulgarian city across the Belasica mountain range, the region held a distinctive position throughout the latter half of the 20th century, sitting at the intersection of capitalist Greece, communist Bulgaria, and Third World Yugoslavia, marking a historical and ideological crossroads.

For reasons such as this, all through her lifetime, Baba Vanga had to grapple with a multitude of identities—Bulgarian, Serbian, Yugoslav, Macedonian—reflecting the experiences of many in the region. This intricate journey ultimately led her to embrace a distinct local identity, one that held profound significance in her heart.

1911-1941: “And I looked, and behold, a pale horse: and his name was Death…”

As World War I commenced, Vangelia’s father, Pande, was mobilized into the Bulgarian army. Tragedy struck when her mother passed away when Baba Vanga was merely three years old. Raised in the home of a neighbor, the girl later witnessed her father’s remarriage upon his return from the war.

In 1923, due to financial difficulties (Vanga’s father lost his land), the family moved to the village of Novo Selo in Macedonia, between Strumica and Petrich. It was there, at the tender age of 12, that Vanga lost her sight after “being carried away by a hurricane.” Legend has it that as she journeyed home with her cousins, near the end of November, a powerful whirlwind lifted her high into the air, eventually dropping her several hundred meters away. She was discovered much later, ensnared in branches, her eyes filled with dust and debris. Given their limited means, her family could not provide the necessary treatment, so her sight gradually faded away, leaving her completely blind.

In 1925, Baba Vanga was sent to the Home for the Blind in Zemun, Serbia, where she spent three years learning to cook, knit, and read Braille. There, she met a blind young man from a well-to-do family who planned to marry her. However, due to some family hardships (her stepmother died during her fourth childbirth), Vanga had to return to her father’s house in Strumica to help care for her younger siblings—her brothers Vasil and Tome, and her sister Lyubka.

The death of Vanga’s father in 1940 plunged the family into dire straits, teetering on the edge of starvation. It is this moment of desperation that marked the turning point in Vanga’s connection with the supernatural realm. Her first great revelation coincided with the entry of Hitler’s troops into Yugoslavia on April 6, 1941. It was the vision of an ethereal figure on horseback, a “light rider”, who spoke to her of blood and death and destruction, of an impending war in the East that would leave millions and millions grieving…

A story of nation-building: the ancient civilization that never was

Decades later, from her chosen perch in the humble village of Rupite—a mere 10 kilometers northeast of Petrich, nestled within the very heart of an extinguished volcano’s crater—Baba Vanga, drawing from a supposedly sacred wellspring of energy and intuition, in the midst of one of her visionary trances, would allude to the enigmatic identity of the ethereal rider of April 1941:

Here, where I stand, there was once an ancient city, luminous and resplendent, its streets bustling with the brilliance of cultured souls—the last descendants of an illustrious bygone civilization… Their god, a knight in shining armor, all of gold and gems, could not save his people from the disaster. In my trances, I can still hear the cries and pleas of these once-mighty beings, swept into the fiery embrace of the volcano in the blink of an eye, a chorus of horror, beauty and strength…

In an immensely insightful article on Baba Vanga, Galia Valtchinova—Professor of Anthropology at the University of Toulouse and Senior Research Fellow at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences—identifies a connection between the “light rider” image and the Thracian horseman, a key symbol from ancient Thrace. The connection, in Valtchinova’s opinion, highlights the persistent yearning of modern Balkan nations to shape alternative historical narratives for themselves, particularly when facing uncertain futures. In the case of communist Bulgaria, this involved aligning with ancient Thrace, while sidestepping Hellenistic and Christian influences.

In other words, to Bulgarians, Baba Vanga was a unique phenomenon. She wasn’t merely a contemporary Pythia, the high priestess of Apollo’s Temple at Delphi; she represented a singular Bulgaro-Thracian tradition spanning several millennia, all the way to classless pagan times, and referenced as such even by Herodotus himself, in the seventh book of his Histories:

The Satrae, as far as we know, have never yet been subject to any man […] It is they who possess the place of divination sacred to Dionysus. This place is in their highest mountains; the Bessi, a clan of the Satrae, are the prophets of the shrine; there is a priestess here who utters the oracle, just as at Delphi.

1941-1967: “I see dead people…”

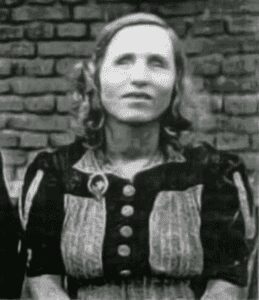

Baba Vanga became Baba Vanga gradually, in two distinct phases. At first, she held the humble role of a local clairvoyant, in the literal sense of that word—she could see clearly things others couldn’t. During the Second World War, she became regionally famous not by making grand, sweeping predictions about the future, but by telling visitors where their missing family members could be, and whether they were dead or she could see them returning.

“They come a lot, the spirits, and all of them are different,” Baba Vanga told her niece once. “When they start talking to me—or rather, through me—I lose a lot of energy, I feel bad… But I can’t help it. When a person stands in front of me, all their dead relatives gather around him. What I hear from them, I pass on to the living.”

Owing to this connection Baba Vanga had with the hereafter, soldiers and their relatives—both of them tortured by uncertainties and in desperate need of solace and human contact—developed a particularly strong belief in her clairvoyant abilities. To them, it didn’t even matter what she was saying; what mattered was that she was saying it to them.

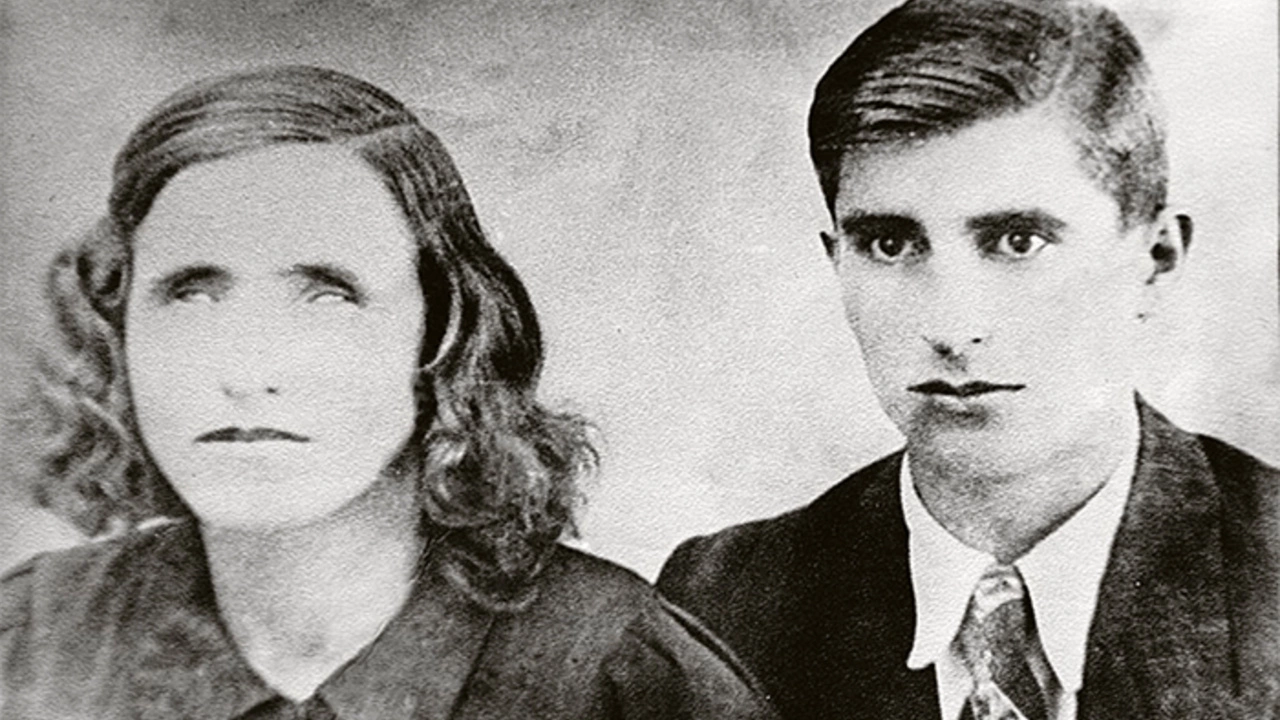

In early 1942, Vanga received a visit from a Bulgarian soldier named Dimitar Gushterov. He sought her help in uncovering his brother’s murderer. Vanga agreed to assist him on the condition that he wouldn’t seek revenge; once he pledged, she revealed the killer’s identity. Impressed and enamored, Gushterov returned months later to propose marriage.

The couple wed on May 10, 1942, and settled in Petrich. The marriage, sadly, was an unhappy one, marred by Gushterov’s alcoholism. He passed away from cirrhosis at the age of 42, in 1960. By then, the childless union had further elevated Vanga’s status and sanctity. In the eyes of many, right until the very end, she remained pure, a divine virgin, touched by a god, and not by men.

Cold War politics, a different kind of game

“Communist governments,” writes Judith Joyce in The Weiser Field Guide to the Paranormal, “as a rule, persecute, or at least do not encourage fortune-tellers, who are considered to be example or vestiges of primitive superstition. Baba Vanga, though, has been described as ‘the only state-sponsored oracle in modern times.'” So, how did that happen? The answer lies in a combination of factors.

First of all—and unsurprisingly—as Baba Vanga’s wartime renown grew, she increasingly captured the attention of political circles; there is a persistent rumor that King Boris III himself visited her on April 8, 1942. This phenomenon only heightened after the war, with Vanga’s Petrich residence witnessing a steady stream of Moskvitches and Chaikas, belonging to post-war Bulgarian politicians. Before too long, whispers began circulating that notable political figures from both the West and the Soviet Union were frequent visitors too, attracted by some of Baba Vanga’s predictions.

Such a backdrop isn’t entirely surprising given the era’s global turbulence—this was the time of bizarre CIA projects such as the MKUltra and MKNAOMI, the time of heart attack guns and lipstick-pistols. In such atmosphere, it was only natural for the Bulgarian government to eventually realize that Vanga could be more than just a “psychic baba”; she could be a valuable asset.

So, in 1967, they made her a civil servant, affiliating her to the newly-found Institute of Suggestology, established within the Bulgarian Academy of Science. The move entitled Baba Vanga to an official salary of about $200 per month. Moreover, her consultations came at a fee now: $10 for citizens of socialist states and $50 for those from the West. Vanga was additionally granted a special residence in Rupite, two secretaries to handle admissions, a personal car, and a dedicated driver.

Simultaneously, a special hotel was constructed in Petrich for visitors, reflecting her growing popularity. By the 1970s, as her fame spread throughout Bulgaria, Baba Vanga was hosting around 100.000 visitors annually! It was during this period that her predictions took on a more political hue, intertwined with a deeper understanding of her visitors’ past. This evolution could perhaps be attributed to specific reasons.

1967-1995: “The only state-sponsored oracle of modern times”

Over the course of the Cold War, as part of the Stargate Project, the CIA spent millions of dollars researching paranormal abilities for espionage and military applications. Reportedly, their research extended to Baba Vanga herself, after they were allegedly upset by several predictions that came true, as well as by her rumored knack for receiving visions straight from NATO’s European military bases.

Bulgaria’s interest in Baba Vanga, however, had little to do with her rumored abilities. “It was prestigious,” in the words of mentalist and skeptic Yuri Gorny, member of the Commission on Pseudoscience, “for a small country to have a world-famous soothsayer, to whom crowds of tourists and celebrities from all over the world would flock; particularly if many of them were politicians.”

Amidst a fractured global landscape, Baba Vanga stood as a potential force of unity that could be harnessed for popular manipulation. Indeed, a considerable number of Baba Vanga’s predictions were frequently interpreted in ways that aligned with specific governmental narratives or strategies. Moreover, Lyudmila Zhivkova herself—daughter of Bulgaria’s supreme leader Todor Zhivkov, a keen believer in spirituality—became a close friend of Vanga, an advocate, a follower.

Most importantly, Petrich and Rupite quickly evolved to become hubs for gathering information on prominent national and international figures. Hotel staff and taxi drivers collected details about eminent visitors (which may have even included Leonid Brezhnev in the 1970s!), and then shared these details with members of the Committee for State Security, Bulgaria’s very own KGB (known locally as DS).

Naturally, many of these insights found their way to Baba Vanga too, enhancing (as it were) her clairvoyant capabilities. For instance, during two covert visits, Todor Zhivkov was supposedly taken aback by her precise knowledge of intricate facets of his life. Little did Zhivkov know, however, that it wasn’t Vanga that knew these things, but Angel Solakov, the head of the DS; he got there a little earlier.

A parting prophecy

After the fall of communism in 1991, Baba Vanga funded the construction of “an extremely unorthodox Orthodox church” within her personal sanctuary in Rupite. Not long after, on August 11, 1996, she passed away, aged 84, due to right breast cancer, declining medical treatment or surgery. Her funeral drew tens of thousands of attendees. Within just a few months, the murals inside the church had to be retouched, having been worn out due to myriads of kisses. As her executor, Dr. Napoleonov—Petrich’s most senior public figure—solemnly announced that Vanga had left all her property, including her homes in Petrich and Rupite, to the state. In death, as in life, she possessed nothing—it was her country that possessed her.

For Russian physician E. B. Alexandrov, long-time president of the Commission on Pseudoscience, this was a match made in heaven: Baba Vanga, he claims, was “a well-sponsored state business,” earning millions of dollars for the Bulgarian state in the span of a few decades. The Orthodox Church didn’t like her either: to them,, she was a witch, a Baba Yaga, an agent of the devil. Finally, for Bulgarian journalist Svetoslava Tadarykova—who conducted a detailed investigation of Vanga’s life and even uncovered photographs of DS officers linked to her—Baba Vanga was, “without a doubt, an agent of the State Security department and full-time collaborator with the Special Services from 1971 to 1984.”

For most people, however, she was—and still is—a legendary prophet, a mythical being, a modern Xenoclea. As a result, it’s difficult to know what Baba Vanga predicted, and what’s been merely ascribed to her, post eventum. Among other things, she is said to have foretold both Stalin’s death and Gorbachev’s rise; the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the September 11 attacks on the United States; the Chernobyl disaster and the sinking of the Russian submarine Kursk in 2000; at least half of the 1994 FIFA World Cup final, as well as the victory of Bulgarian GM Veselin Topalov in the FIDE World Chess Championship 2005.

No written records, ante eventa, exist to verify any of this. That millions of people came to Baba Vanga in search of something more than reality could offer—that’s an unquestionable fact; that many of these still believe to have talked to an otherworldly being, that can’t be questioned as well. Everything else, however, is mere speculation. True, it may have been that Baba Vanga predicted this or that because she had friends in high places. What’s far truer, though, is that she could “predict” everything else simply because millions of people want to believe that there’s something beyond reality. This rings particularly true in crisis-ridden nations governed by superstitions and corrupt leaders, like the Balkan countries.

In many ways, it wasn’t Baba Vanga’s predictions that gave rise to crowds of devotees; rather, it was the crowds of devotees who gave rise to Baba Vanga. And as long as there are oppressed countries and downtrodden people—stripped of all hopes and prospects—figures like Baba Vanga will persevere. That prophecy is on us.