One of history’s most gruesome diving accidents occurred on November 5, 1983, aboard a North Sea oil rig called the Byford Dolphin. Explosive decompression killed four divers and an attending crewman instantly. It only took one hatch, mistakenly opened during a routine procedure, to cause the accident; under extreme pressures, even that minor slip-up had disastrous consequences.

To fully grasp what happened to the crew of the Byford Dolphin, it’s necessary to understand the dangers of diving. When it comes to working underwater, pressure is everything. For every 33 feet (10 meters) a person descends, the ambient pressure increases by about one atmosphere’s worth, equivalent to 14.6 pounds (6.6 kilograms) on every square inch of your body. At a depth of 250 feet, that’s more than 125 pounds per square inch.

This puts serious limits on divers. The main problem with diving is not actually going under high pressure, but coming out of it; deep enough underwater, the force exerted on the body is such that nitrogen gas compresses to a fraction of its normal volume, and ends up dissolved in the bloodstream. When divers come up too quickly, the sudden release of pressure causes a condition known as decompression sickness, or “the bends.” Dissolved nitrogen suddenly forms bubbles throughout bodily tissues. Effects include nausea, dizziness, severe joint pain, paralysis, and sometimes death. The only way to avoid decompression sickness is by returning slowly and carefully to the surface, allowing time for pent-up nitrogen to diffuse naturally. This process can take hours, or in the case of deep-water dives, days—a prohibitive restriction when it comes to oil drilling, maritime salvage, and other situations where people have to work for extended periods in the deep sea.

The Byford Dolphin saturation divers

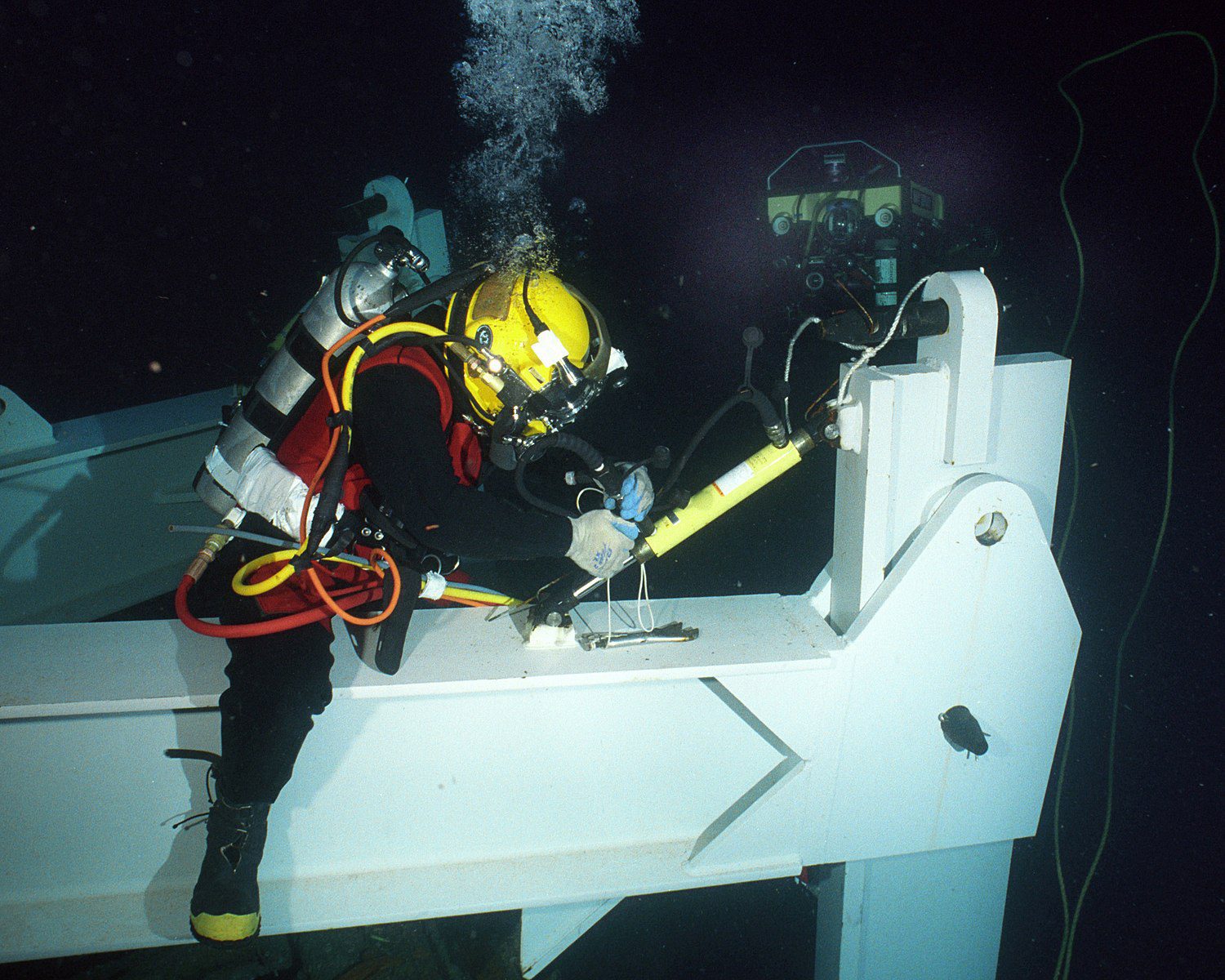

Saturation divers are elite professionals that can operate at considerable depths because they live constantly under high pressure, for up to 28 days at a time. During the 28 days, their living quarters are maintained at the same pressure as the bottom of the ocean, allowing them to commute back and forth with relative ease.

Workers aboard the Byford Dolphin used saturation diving to deploy and maintain drilling equipment in the depths of the North Sea. Between shifts, the divers inhabited a specialized chamber system, on the rig’s deck, pressurized to nine atmospheres—which is to say, 131 pounds (60 kilograms) per square inch. They traveled between this chamber and the work site using a diving bell, operated by specialist tenders. At all times, the divers had to remain under intense pressure, and extensive procedures were in place to move them around without any exposure to the outside world.

The fatal error that caused the Byford Dolphin Accident

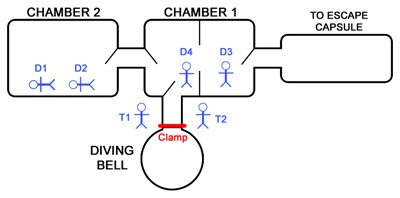

The chamber system of the Byford Dolphin had two main compartments, chamber one and chamber two, with a smaller section, called the trunk, connecting chamber one to the diving bell. Two diving tenders on the outside supervised the crew transfer process and operated the various hatches involved. Only once the door to chamber one was shut, sealing the saturation divers in their pressurized living quarters, could the trunk be reduced to normal atmospheric pressure. At that point, the tenders could safely undock the diving bell.

At 4:00 am on November 5, 1983, two dive tenders, William Crammond, and Martin Saunders, assisted the return of saturation divers Bjørn Bergersen and Truls Hellevik. Another two divers, Roy Lucas, and Edmund Coward, were resting in chamber two. The diving bell door was already closed, and the returning divers had entered chamber one. Hellevik was supposed to shut the interior trunk door, sealing chamber one, after which Crammond would vent air from the trunk, and finally open a clamp to release the bell. This was a normal procedure; everyone involved was highly experienced in saturation diving and had done this many times before. No one knows why Crammond opened the outside clamp before Hellevik could close the inner door. It’s only known that he did—and the results were immediately catastrophic.

Explosive decompression

The moment the trunk was unsealed, all the high-pressure air in the chamber system was free to vent through the trunk into the outside world, and it did so with tremendous force. Remember the figure from earlier: every square inch was under 131 pounds of pressure. It was enough to push the diving bell into the two tenders. Crammond died immediately, while his colleague Saunders was severely injured.

The strangest effects, however, were reserved for the divers. Three of them—Lucas, Coward, and Bergersen, who were all far from the door—had their blood literally boil as enormous amounts of dissolved nitrogen suddenly became gas again. They were killed instantly. Postmortem analysis revealed that their arteries, veins, hearts, and livers were clogged with fat, precipitating out of the bloodstream.

The fourth diver, Hellevik, had the most gruesome death of all—he was pinned against the jammed interior trunk door, which was open by a crack, and the escaping air forced him through it, dismembering him and launching vital organs as far as 30 feet (10 meters) away. Like the other divers, he didn’t live long enough to know what had happened; it was all over in a moment.

Aftermath of the Byford Dolphin incident

While the immediate cause was human error, the deadly events of November 5 led to a subsequent investigation that revealed deeper problems in the industry. For decades afterward, the North Sea Divers Alliance—a group of active divers and the victims’ relatives—maintained that negligent higher-ups had issued the Byford Dolphin divers faulty equipment. Their pressure chamber system had been obsolete even then, lacking appropriate fail-safes that would have prevented the disaster.

Ultimately, the campaign proved successful; in 2008, the Norwegian government conceded that the accident was due to inadequate safety measures, and it awarded damages to the families of the four divers. Improvements in the practice of saturation diving have prevented similar mishaps from taking place. To this day, however, the Byford Dolphin incident is a testament to the frightening power of pressure and the dangers of working at extreme depths.