In 1786, a barrister named William Jones arrived in Calcutta, ready to take up an appointment as a judge at the Supreme Court of Bengal—a court newly established by the British to uphold the law in its prize colony.

He would soon find, however, that the locals already had a fully functioning legal system, based on texts written in the classical Indian language of Sanskrit—and that despite the fancy new European building, they’d be continuing to cite these texts in court. For the court to succeed, Jones realized he needed a way to fuse British and Indian law, and to do that he was going to have to learn India’s ancient language.

Jones was a passionate linguist, and he soon became enamoured by Sanskrit. But what struck him as particularly remarkable was how time and again, he would notice similarities to languages with which he was familiar, including Greek and Latin. Grouping these two with Sanskrit, he famously observed:

No philologer [linguist] could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source which, perhaps, no longer exists.

It wasn’t actually the first time anyone had made this suggestion: a Dutch scholar called Marcus van Boxhorn had proposed something similar over a hundred years earlier. But Jones was a hotshot polymath who hung out with Benjamin Franklin in Paris, so it’s Jones’s quote that features in every introductory linguistics textbook today.

Jones’s (and van Boxhorn’s) hypothesis—that the languages of Europe and India descend from a shared great-grandparent—is nowadays widely accepted. Linguists have reconstructed sentences and even stories in it, and mythologists have an idea of the speakers’ religion. Sadly, the misuse of Jones’s suggestion also attracted racist ideologues, including the Nazis. But this is a language which was never written down and which died out many millennia ago. So how can it have influenced us so much—and how can we even know anything about it?

Reconstructing a dead language

The attempt to understand this language—known as “Proto-Indo-European”—gave rise to the discipline of historical linguistics. To understand how this works, we need to know that language never stays static. Just as the clouds cannot remain still but must change as they drift across the sky, so must words move and transform over time.

However, these changes are not wholly random. For one, sounds don’t just change in one individual word at a time, but consistently across a language. For example, English is essentially the result of many sound changes from German, and the English word “thank” comes from the German danke. And there are many words featuring a “th” in English that take a “d” in German: “these” is diese, “three” is drei, and so on. This is all the result of the Anglo-Saxons, who left Germany to settle England, shifting their pronunciation of “d” after their move.

Notably, a “d” is quite likely to change to a “th” over time, because the two sounds are made in a similar place in the mouth (at the front, with the tip of the tongue touching the teeth). However, a “d” would not be likely to change to a “k,” for example, as the latter sound is made right at the back of the mouth.

Read more: The Statue of Unity: A Colossal and Controversial Wonder

By studying these kinds of regular shifts, linguists can get a pretty good idea of the common ancestors of languages, which ultimately allows them to piece together large-scale language families, like Indo-European. This family consists of northern Indian languages like Hindi and Gujarati, as well as Persian (spoken in Iran) and nearly all the languages of Europe (including English, French, Russian, Greek, and Welsh). The only exceptions in Europe are Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian (which form another family)—and Basque, which exists on its own in northern Spain unrelated to anything else, and is probably the remains of what was spoken before the Indo-Europeans arrived on the continent.

But given that the original ancestor is long extinct, can we have any idea where all of this got started?

The search for a homeland

Though we have no written evidence of the Proto-Indo-European language, we can still garner clues as to where it was spoken by considering its vocabulary. For example, all Indo-European languages feature related words for “honey,” such as miel in French, mil in Irish and madhu in Sanskrit. (English has “mead,” a drink made from honey). That means Proto-Indo-European must have been spoken somewhere with bees: if these cultures had discovered bees and honey separately, they would have each come up with their own words.

We likewise know that the Proto-Indo-Europeans had sheep, dairy foods, dogs, and horses. We know roughly what plants existed in their homeland, giving us hints to the climate. Crucially, we also know that they had a detailed vocabulary for wheels and wheeled vehicles. The Indian word chakra, meaning wheel,” is related to “circle” in English; words like “rotate,” “axle,” and “wagon” all have relatives across Indo-European languages too.

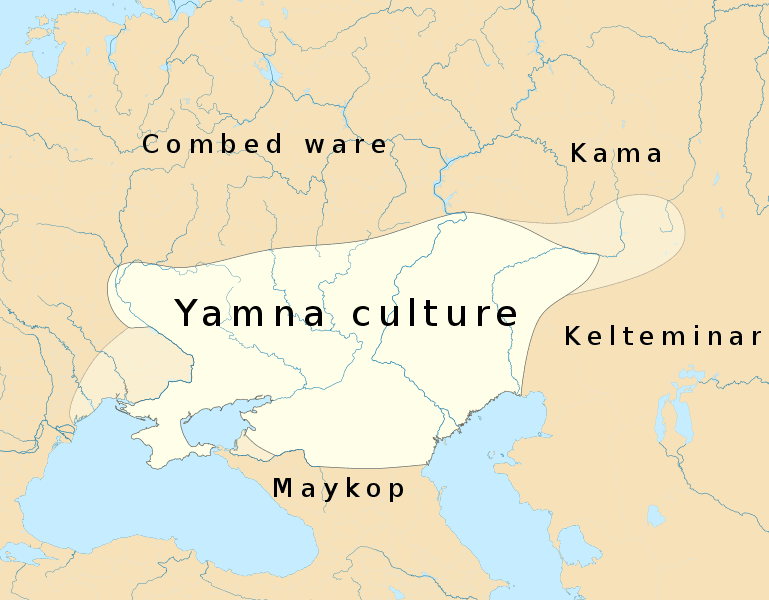

Combining this kind of linguistic clue with the earthy evidence dug up by archaeologists, academics have pinpointed a culture known as the Yamnaya as the leading contender for being the original speakers of the first Indo-European language. This culture existed on the steppes of Ukraine and southern Russia around 5,000 years ago.

The Ukrainian steppes are vast, almost featureless grassland plains, similar to the American prairies. Wild horses are native to the region and were domesticated by the Yamnaya. Having then acquired the wheel (which likely spread there from what is now Iraq), they managed to use their horses to draw wagons and chariots. The Yamnaya buried their dead in distinctive mounds known as kurgans, often alongside horses and wagon parts, showing these items’ significance to their culture.

Evidence will always be incomplete for periods so deep in history, but it’s becoming increasingly accepted that the Yamnaya people were the speakers of Proto-Indo-European. Their horse-driven vehicles would certainly have made them a formidable force. And archaeologists have found evidence of their kurgan burials spreading eastward into Europe. Furthermore, many of the cultures that descended from Proto-Indo-European saw the horse as a symbol of power. Perhaps it was venerated as the source of their ancestors’ success?

Sky gods

Whether the Yamnaya are the source of the Proto-Indo-European language or not, we can also use the mythologies of Europe and India to piece together something of the Proto-Indo-Europeans. We are on shakier ground here, however. Myths do not change according to regular, predictable laws like languages do. And they are often freely adopted from abroad: Ancient Greece, for example, incorporated many elements from Egypt (which is not an Indo-European culture).

Still, some similarities seem too strong to ignore, such as that between Thor and Indra at the start of the article: two thunder gods who slayed giant snakes. To this we can add the Ancient Greek deity Zeus—another god of thunder and the leader of the pantheon—who wrestled the serpent Typhon for control of the world.

In fact, Indo-European cultures usually have a sky or weather god as their chief deity. And this is in tune with an origin on the steppes: out on those unremitting, wide-open plains, the grand skies would have been by far the most dramatic feature. In the absence of mountains or oceans, perhaps it makes sense that they would look to the sky as the source of the world’s mysteries?

The Aryans

After William Jones’s proposal in the late 1700s, Indo-European studies captured the imagination throughout the 1800s—but sometimes for the wrong reasons.

People in the 1800s were disturbingly interested in classifying races. The idea of a single great people, who lay behind many of the world’s great cultures, proved popular. Of course, everyone proposed that this culture originated where they came from. But such ideas resonated particularly strongly in Germany. Germany was still “finding itself” in the 1800s: the Germans entered the century a people with no nation, their territory split between hundreds of tiny states. German nationalists sought to encourage German speakers to come together to form a powerful country, and the idea of having once been a strong super-race was an appealing source of inspiration.

Read more: DNA Confirms Hunter Gatherers and Ancient Farmers Had It Going On

It was from such a cocktail of ideas that Hitler later drew elements of his philosophy. He took the word “Aryan” from a word used by writers of old Indian and Iranian texts to describe themselves (the word “Iran” comes from “Aryan”), and he adopted the ancient Indian sign of the swastika. He believed that these were relics of an ancient “master race” that had once conquered the world (before being “diluted” by contact with the locals).

But Hitler’s ideology had no basis in reality. For one, the Indo-Europeans were not a “race.” Languages are not genes. For example, the peoples of places influenced by the Roman Empire ended up adopting Latin (which developed into its daughter languages of French, Italian, Spanish, and so on) because it was a prestigious language at the time. They were not replaced by people from Rome. The Indo-European languages probably spread over the millennia through a mixture of invasion, trade, settlement, and inter-marriage. In any case, there is certainly no way to mark out who is an “Indo-European” using genes.

Furthermore, Hitler persecuted, for example, Slavic people while arguing that they were “inferior,” even though Slavic languages trace back to exactly the same origin as German. This makes it clear that Hitler was simply following his own prejudices, and haphazardly using whatever pseudo-scientific justification he could find to support them.

And whoever the Proto-Indo-Europeans were, there is no evidence that they were “superior” to their neighbors. For example, the elaborate burials found at Varna, Bulgaria, precede the arrival of the Yamnaya into the region and are more sophisticated than anything we find from them. If the hypothesis of the Yamnaya spreading outwards from the steppes is correct, it is because they were simply in the right place at the right time: horses were native to their region, and once they obtained the wheel from the Middle East, they found themselves in control of a powerful weapon.

There is much about the first Indo-Europeans that is now lost to time. In our attempts to know them, we are forever snatching at fragments. They left us no towering pyramids like the Ancient Egyptians; they left us no lofty philosophy like the Greeks. Yet, to think that the very sounds we utter today can be traced back to men and women living out their lives on a vast, desolate plain 5,000 years ago—to imagine them shearing sheep, gathering honey, and telling stories under a sweeping sky—gives us a tantalizing connection to a profoundly distant past. And for that, the first Indo-European speakers hold a fascination like no other.