Looking back, it could have all been a simple love story—had it happened at a different time, in different circumstances.

But at the height of the Cold War, international love stories were rarely simple. This one includes two high-profile murders, several vicious twists, and an unlikely Capitol Hill ending, with Idaho Senator Frank Church confronting CIA director William Colby about a mysterious heart attack gun, in the Indian summer days of 1975.

About two decades earlier, on the other side of the Iron Curtain, a 26-year-old Soviet spy by the name of Bohdan Stashynsky fell in love with Inge Pohl, an unassuming German hairdresser. One could argue, that’s how it all began.

Bohdan Stashynsky, a fare dodger turned Soviet spy

Bohdan Nikolayevich Stashynsky, born 1931, was an unexceptional 19-year-old student at the Faculty of Mathematics in Lviv when he was caught fare-dodging on a train. A seemingly minor offense, it would soon take him down the darkest of paths.

Under threats of arrest and imprisonment for his family’s connections to the Ukrainian nationalist underground, Stashynsky was forced to spy on the anti-Soviet movement in his hometown. After a few years, his handlers in the KGB saw potential in him and recruited him as a top-level spy.

At the end of 1954, Stashynsky moved to Berlin-Karlshorst, where he assumed the identity of Josef Lehmann, a supposed refugee from Stargard, Poland. His Slavic accent, he explained, was a product of traumatic past experiences: his father and mother had died during the war, and he had to live as an orphan under Polish rule for nine years.

Listed as “a displaced person,” Stashynsky got a job as a punch card operator at a state-owned enterprise (VEB) in Karl-Marx-Stadt (today’s Chemnitz). By the end of 1955, he shed most of his native accent. By the beginning of the following year, his training as a spy was complete, and he returned to East Berlin—as a KGB agent.

The first non-Soviet wife of a KGB agent

In April 1957, while dancing at Friedrichstadt-Palast in East Berlin, Stashynsky (as Josef Lehmann) met Inge Pohl, an East German hairdresser. He was beguiled by her beauty, modesty, and ethereal presence; she, in turn, was impressed by his charming personality, good looks, and well-tailored clothes—not to mention the fact that, at 26, he was the owner of his own apartment.

The two began dating and eventually fell in love. At the time, Stashynsky served as an instructor and courier for the KGB, carrying messages to other agents in West Germany, and emptying dead letter boxes. To maintain cover, he got a job as a car mechanic and, later, as an interpreter.

In April 1959, two years to the day after meeting Pohl, he told her his real name and profession, and then boldly proposed. It was a long and painful discussion, soaked in sobs and tears, but Pohl eventually said yes. In March 1960, she became the first non-Soviet wife of a KGB agent. Even then, she didn’t know that she had just married one of the world’s most notorious assassins.

Indeed, at the time, only the highest echelons of the KGB knew that Bohdan Stashynsky was the murderer of Lev Rebet and Stepan Bandera, anti-communist émigrés living in Munich, the main organizers of the Ukrainian nationalist underground in exile.

The murders that (never) happened

Not long after Lev Rebet had collapsed, in the morning hours of October 12, 1957—while on his way to the editorial offices of the “Ukrainian Independent” at Karlsplatz 8 in Munich—German doctors declared it a natural death from heart failure. Nothing suggested otherwise. Stashynsky was one of the very few people in the world who knew this to be a laughable misdiagnosis.

That morning, at what was (at the time) a prominent tram stop, he had shot Rebet in the face with a special KGB secret weapon—a heart attack gun. “Today, I met a celebrity in Munich and congratulated him on his triumphs,” he reported to the KGB. “I am sure that the greeting was cordial and successful.”

Two years later, on October 15, 1959, Stashynsky achieved an even greater feat when he assassinated Stepan Bandera, the famed and still controversial leader of the Ukrainian resistance in Munich, using the same method as he did with Rebet.

On that fateful day, Bandera (hiding under the pseudonym Stefan Popel) went back to his apartment on Kreittmayrstrasse 7 just moments after getting out, leaving his bodyguard waiting at the front. Shortly thereafter, a cry was heard and when the neighbors went to investigate, they found Bandera lying lifeless on the stair landing.

Once again, it all pointed to a heart attack. However, upon conducting an autopsy, it was revealed that the true cause of Bandera’s death was cyanide poisoning. Still, the best guess of the Munich police at the time was that it was probably a suicide. The CIA feared assassination, but they had no concrete evidence to support their suspicion.

On the other side of the Iron Curtain

As Bandera’s murder was rapidly turning into a cold case, Stashynsky’s loyalty to the Soviet regime began to wane. He had been tasked with translating some books from German and, through them, he learned of the living conditions in the West and the stark contrast with life in the Soviet Union. He decided to risk it all and tell his wife everything. Hours later, having collected herself, she began begging him to confess to his crimes and seek asylum in the West.

In 1961, Pohl had to go to Germany to give birth to the couple’s first child, a son, Peter. When the child suddenly died in August 1961, the couple decided to use Peter’s East Berlin funeral as an excuse to defect to the West—incidentally, on the very same day that the Wall was erected. Stashynsky got all the travel permissions from the KGB. To their dismay, he never showed up at his son’s burial site.

It was during Stashynsky’s debriefing with the CIA in West Berlin and other intelligence agencies in Frankfurt that he revealed his involvement in the assassinations of Lev Rebet and Stepan Bandera. At first, nobody believed him: as far as the West was concerned, Rebet wasn’t even assassinated, and Bandera could have only been poisoned by someone close to him or, at worst, a group of people capable of quickly overpowering him.

Only after Stashynsky recreated the assassinations for the West German police—the CIA had given up on him completely!—his claims were taken seriously, and his stories finally believed. Among other things, these stories suggested that the Soviets had somehow developed a spray gun that could release a burst of cyanide gas from a crushed capsule. It was now America’s turn to up the ante.

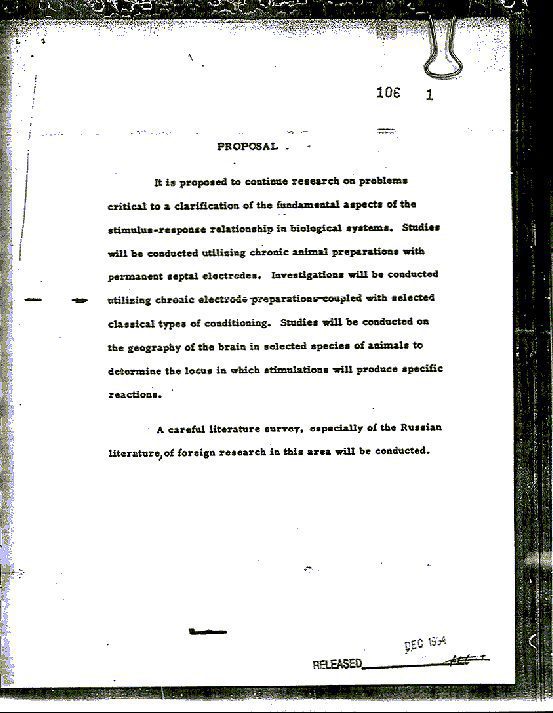

MKUltra and MKNAOMI, CIA’s mind control programs

Long before Stashynsky used a heart attack gun to assassinate Rebet and Bander—and probably as early as May 1952—the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States had began a joint project with the special operations division of the Army Biological Laboratory at Fort Detrick, Maryland. Its codename was MKUltra, and its goal (in the unminced words of American journalist Stephen Kinzer) “a continuation of the work begun in WWII-era Japanese facilities and Nazi concentration camps on subduing and controlling human minds.”

During the course of the project—and supposedly driven by fear of “Soviet brain perversion techniques”—the CIA accumulated substances that could induce various deadly diseases, including “tuberculosis, anthrax, encephalitis (sleeping sickness), valley fever, salmonella food poisoning and smallpox.” At some point, MKUltra changed its codename to MKNAOMI, but it didn’t really change its mission: “to find countermeasures to chemical and biological weapons that might be used by the Russian KGB.”

The existence of MKUltra and MKNAOMI remained a secret for decades. But in the 1970s, spurred by a now-iconic New York Times article by journalist Seymour Hersh, a series of investigations and congressional hearings brought the programs to light. It was revealed that the CIA had conducted illegal and unethical experiments on unwitting subjects, including administering all kinds of poisons and mind-altering drugs, and subjecting individuals to extreme psychological and physical torture.

It was also revealed—among other equally unbelievable and disturbing things—that the agency had developed their own version of the Soviet heart attack gun, a far more sophisticated one, verbosely described in a CIA memo as a “nondiscernible microbionoculator.”

The CIA heart attack gun, a “most efficient murder instrument”

By the looks of it, the development of the heart attack gun began not long after Stashynsky’s confession. According to whistleblower Mary Embree—who started working as a secretary in the CIA’s Audio-Surveillance Division and later moved to the Technical Services Department—she was the one to be entrusted with the task of discovering a deadly poison that could cause a heart attack without being detected during an autopsy. After some time, she came up with saxitoxin, aka the shellfish poison.

Saxitoxin is an almost undetectable, highly potent neurotoxin produced by certain species of algae. It is commonly found in shellfish, such as mussels, clams, and oysters, that feed on these algae. Saxitoxin blocks the movement of sodium ions across nerve cell membranes, leading first to a tingling sensation in the lips and fingers, and then to a full body paralysis which can cause death within less than 20 seconds. The shellfish toxin is extremely powerful, with as little as 0.1 milligrams per kilogram of body weight being lethal to humans.

In Embree’s explanation, after being extracted from the shellfish, the saxitoxin was then frozen into some sort of a dart and finally shot from a pistol, at a very high speed, into the person of interest. As a result, upon reaching the person, the toxin would melt inside them, leaving behind nothing more than a tiny red dot on their body, extremely hard to detect even with high-precision instruments.

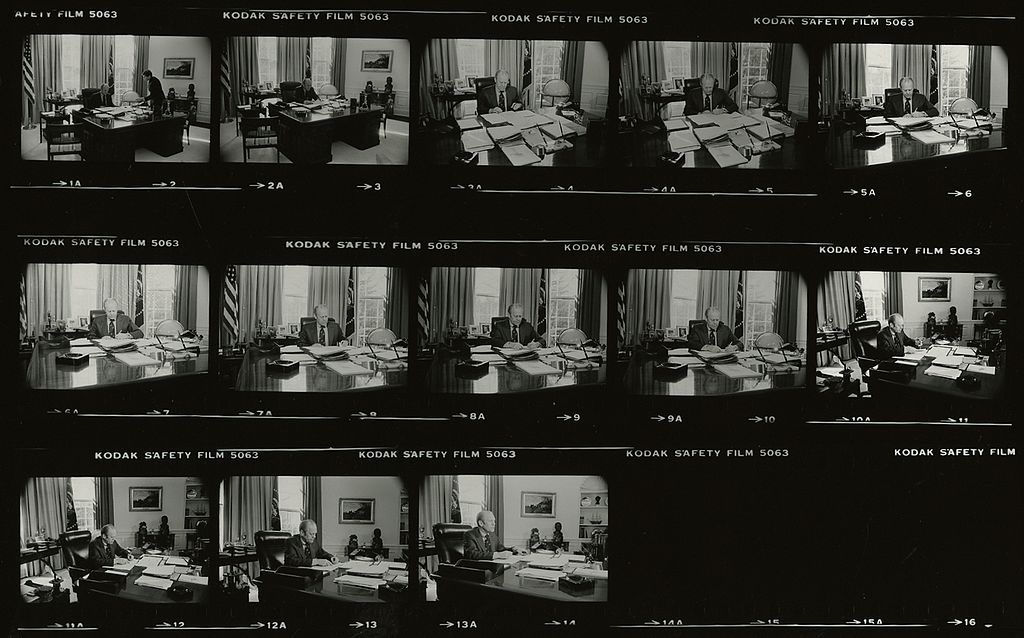

During a Church Committee hearing in 1975, the CIA Director William Colby unveiled this terrifying weapon to the American public. The CIA heart attack gun, it turned out, was actually a modified Colt M1911 pistol with a sight mounted on the top, and a battery fitted inside the handle. It utilized electricity to shoot a dart at the intended target, and could do so noiselessly and accurately at distances up to 100 yards (about as many meters). “A murder instrument that’s about as efficient as you can get,” muttered Senator Frank Church, echoing the opinion and shock by many of those present at the hearing.

The aftermath (without an outcome)

The heart attack gun was designed to be highly effective in assassinations, allowing the CIA to carry out their operations with maximum efficiency and minimal risk of detection. As a result, it remains unclear just how many people may have been targeted or killed with this deadly and covert weapon over the years.

In 1973, CIA Director Richard Helms ordered that all MKUltra files be destroyed. The names of a few national leaders—such as Cuba’s Fidel Castro or Patrice Lumumba of the Congo—were nevertheless found in the few remaining documents and confirmed by sworn witnesses, suggesting that the heart attack gun may have been used in more than one illegal assassination attempt.

In 1970, President Richard Nixon ordered the destruction of all toxins and poison weapons in the US military’s arsenal. Even though this probably put an end to the development of the heart attack gun as a military weapon, former CIA employee Dr. Nathan Gordon revealed in 1975 that, at his direction, much of the shellfish toxin was never destroyed but hidden for potential future use.

Following the recommendations of the Church Committee, on February 18, 1976, President Gerald Ford signed Executive Order 11905, which prohibited the US government from “engaging in, or conspiring to engage in political assassination,” in addition to banning the “experimentation with drugs on human subjects.”

License to kill: the James Bondian Cold War

The KGB’s arsenal of unusual weapons—informs Chuck Willis in the Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weaponry—was deviously James Bondian. A 4.5mm gun disguised as a lipstick (known, poetically, as “the Kiss of Death”) was just one of many weapons used by Soviet women spies and female KGB agents. Other weapons included poison pens, gas-firing cartridges concealed in wallets, and the infamous Bulgarian umbrella, which was used to assassinate Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov in London, in 1978.

But the CIA, too, had its fair share of exotic weapons, and the heart attack gun was certainly one of them. Though the most famous, it may not even have been the most bizarre one. For instance, the agency also worked on a device that could fit inside a single fluorescent bulb and spread a biological poison whenever the light was turned on. Moreover, who can really forget the gay bomb, which was supposed to be able to release pheromones to make enemy soldiers sexually attracted to each other, causing them to become distracted and ineffective in combat!

Whereas we know a lot about KGB’s misdeeds (mostly due to the dissolution of the Soviet Union), the true extent of the CIA’s involvement in clandestine activities may never be fully known. Even so, the legacy of projects such as MKUltra and MKNAOMI continue to cast a long shadow over American history, and the ever-ongoing debate about the role of intelligence agencies in a democratic society. If nothing else, the very existence of the heart attack gun serves as a reminder of the dangerous consequences that can arise when national security is pursued at any cost.