As the final days of World War II drew near, a remote Austrian village named Itter became the unlikely stage for a remarkable chapter in modern military history. Amidst the subsiding chaos and dwindling destruction of war, an unlikely alliance emerged between American and German soldiers, who joined forces to defend a castle which held several high-profile French prisoners of war against a vicious onslaught from a few fanatically defiant Waffen-SS troops, the last bastion of the Nazi war machine.

This seemingly minor event, which unfolded in the shadow of the most devastating global conflict in human history, is one of only two known instances in which American and German troops fought side-by-side as comrades-in-arms, the other being Operation Cowboy which took place just a few days prior, in the small Czechoslovakian village of Hostau.

More than just a unique and unlikely collaboration, the Battle for Castle Itter—as the event would come to be known—was also the sole occasion in the history of the United States where American troops protected a medieval fortress from continuous assault by opposing military forces, as well as “the last—and arguably the strangest—ground combat action of World War II in Europe.”

The haunting transformation of Castle Itter

Hans Fuchs, now 80, was a 12-year-old boy when he witnessed the haunting transformation of the picturesque Itter Castle into a sinister prison by the Nazis over the spring months of 1943. He remembers seeing, from his derelict classroom window, the imposing fortress surrounded by a double barbed-wire fence, and dozing off to the glare of floodlights in his childhood bedroom. What Fuchs couldn’t have known back then was that this castle-turned-prison would soon become the site of one of the most extraordinary battles in modern military history—and that he would get a front-row seat for the hair-raising spectacle.

Dating back to the Middle Ages, Schloss Itter was originally built to withstand sieges and repel invaders. Partially destroyed during the Great Peasants’ Revolt of 1515-26, it was also the place where the last known witch burning in Austria occured, near the end of the 16th century. Local legend holds that the still extant inscription “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here,” taken from Dante’s Divine Comedy, was added to the castle’s entrance doors around this time, possibly at the behest of those tasked with hunting out the chimerical witches of the Alps.

The inscription turned out to be doubly foreboding centuries later, when the German government decided to repurpose Castle Itter as a subunit of the infamous Dachau concentration camp. It was not just another labor camp: it housed a number of VIP captives, including high-ranking politicians and military leaders whom the Nazis hoped to use as bargaining chips in negotiations. Among them were two former French prime ministers (Édouard Daladier and Paul Reynaud), two former commanders-in-chief Generals (Maxime Weygand and Maurice Gamelin), as well as trade union leader Léon Jouhaux, right-wing politician François de La Rocque, Charles de Gaulle’s elder sister Marie-Agnès Cailliau, Georges Clemenceau’s only son Michel, and legendary tennis star Jean Borotra, “the Bounding Basque,” a 4-time Grand Slam winner.

Behind the walls

It wasn’t just the French VIPs who were imprisoned in Castle Itter, but also many of their wives, girlfriends, and/or secretaries. Two of them—Augusta Bruchlen, the mistress of labor leader Leon Jouhaux, and Madame Weygand, General Weygand’s wife—were confined of their own volition, by virtue of loyalty to their men. There was also a small number of Eastern European convicts detached straight from Dachau and used for maintenance and other menial work. Two names are bound to reappear later in our story, so we might as well mention them now: Zvonimir “Zvonko” Čučković, a Yugoslav Croat electrician-turned-partisan who worked as a handyman at the castle, and Andreas Krobot, Itter’s prisoner-cook, known to the French captives simply as Chef André.

It’s another inmate of the same name, André François-Poncet, the French ambassador to Germany from 1931 to 1938, who would later describe life at Castle Itter as “a mixture of brute force, politeness, and occasional attempts at friendship.” Indeed, relative to other German prisons, the castle provided a comfortable experience for these Ehrenhäftlinge, “honor prisoners.” Among other privileges, they had access to converted guest rooms to sleep in, free use of the castle’s library, and the liberty to exercise in the courtyard area. Moreover, the captives also had a connection to the outside world thanks to Čučković, who stole a small short-wave radio from one of the castle’s guards and hid it in Reynaud’s room. The guard himself was not supposed to have the radio in the first place, so he could not report its theft for fear of punishment.

As the tides of the war turned against Germany, life at Castle Itter underwent a gradual but palpable transformation for the worse. Food and fuel became scarce, so the castle’s generators were replaced by candles and lanterns. The VIP prisoners—segregated by political persuasion even in jail!—were now finally united, albeit in discomfort and unease. Sure, they were glad enough to find solace in the shortages, interpreting them accurately as evidence of Germany’s imminent downfall, but they also feared for their lives, as they knew that they might not be worth much to Nazi leaders intent on covering up their own crimes. Even after the German guards deserted Schloss Itter at the beginning of May 1945, the French captives were left stranded inside, as rather-die-than-surrender Waffen-SS units roamed the surrounding forests, thirsty for Allied blood.

Reaching out for help

In the biblical story of Noah’s Ark, as recounted in the book of Genesis, after the floodwaters had subsided and the Ark came to rest on the mountains of Ararat, Noah released a raven to see if the waters had receded enough for the bird to find a place to rest. When the raven didn’t return, he sent a dove, and he sent it three times before it flew back with an olive branch in its beak. At the beginning of May 1945, as the Nazis began retreating from Austria, the high-profile prisoners at Castle Itter decided to do something similar. On May 3, purportedly on a mission for the prison’s commander officer Sebastian Wimmer, they dispatched the always helpful Čučković to look for American help. When nobody came back by noon the following day, they borrowed a battered bicycle from a local shopkeeper and sent Krobot, their cherished Chef André, to the nearest town of Wörgl, about 8 miles (5 km) away.

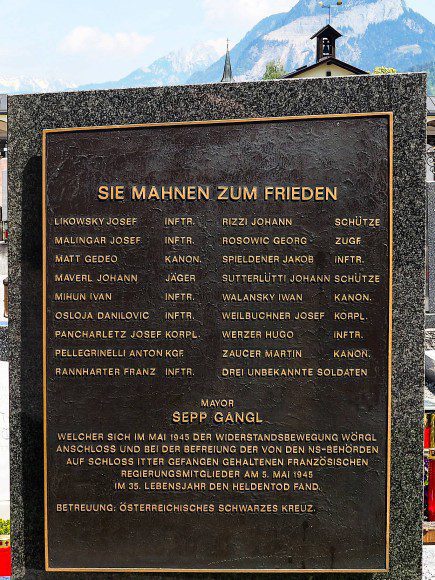

Fortunately—unlike Noah with the dove—the French didn’t have to send Krobot more than once: in Wörgl, quite miraculously, he ran into Major Josef “Sepp” Gangl, a highly decorated Wehrmacht officer, who had switched sides just a few days prior, becoming suddenly the face of the Austrian resistance in the region. Gangl was more than willing to help, but he knew that he could not protect the prisoners—or even reach the castle—on his own, as he only had about 20 soldiers who remained loyal to him. So, Gangl rounded his men and, decking his vehicle with a big white flag, headed toward the town of Kufstein to seek out the nearest American unit. It was there that they encountered the 23rd Tank Battalion of the US 12th Armored Division, which was under the command of newly-promoted Captain John Carey “Jack” Lee Jr, a cigar-chewing, hard-drinking American patriot of old-school honor and immense, self-sacrificing courage.

In the meantime, Čučković—who the prisoners feared was either captured or killed by German soldiers—had managed to bike all the way to the outskirts of Innsbruck, a city 38 miles (60 km) to the southwest of Itter. There, he encountered elements of the 103rd Infantry Division of the US VI Corps and briefed them about the situation at Itter Castle. In the early hours of May 4, 1945, a small rescue force led by Major John T. Kramers—which included a few Sherman tanks and a few dozen infantrymen—set out to liberate the VIP prisoners at Castle Itter. On the way there, they happened upon a group of support-seeking Austrian partisans and came under heavy enemy artillery fire. By the time they made it to the castle—in the afternoon hours of May 5—Lee’s tank, nicknamed “Besotten Jenny,” had already been blasted apart by a German 88mm shell, and Sepp Gangl, survivor of both Stalingrad and Normandy, had been taken out by a sniper’s bullet, while heroically attempting to save the life of former French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud…

Captain Lee to the Dark Tower came

Major Gangl couldn’t have known that he was living out his final hours when he reached Kufstein, as the afternoon drew to a close on May 4, 1945. Standing face to face with Captain Lee, he could sense the exhaustion emanating from the face of the stocky 27-year-old New Yorker, once upon a peaceful time the star player of his high school football team, and now the rough-talking leader of Company B, hoping beyond hope that Kufstein would be his last battle in the European theater of the Great War. Not knowing much English, Gangl handed Lee a letter which shattered that hope with a single stroke of a pen, as it informed the captain of the dire situation at Castle Itter. Despite his fatigue, Lee knew that he had to act, and that he had to act quickly. Even if it required all his remaining strength and resources, it was a battle he could not afford to decline—let alone lose.

Lee wanted to first recon the area before organizing any rescue mission, so he hopped on Major Gangl’s Volkswagen Kübelwagen and headed to Wörgl and Itter, alongside his tank gunner, Corporal Edward “Stinky” Szymczyk, and a squad of Allied Wehrmacht troops. While en route, the eclectic group came across Kurt-Siegfried Schrader, a highly decorated and profoundly disillusioned Waffen-SS officer recently released from duty due to injuries suffered in Normandy. They discovered that Schrader had grown close to some of the French prisoners at Itter while recovering there, and that he had assumed responsibility for their protection in the meantime. A bit later, in the halls of the castle, Lee had a quick conversation with the prisoners, whom he promised to return quickly with “a cavalry.” Before taking off, Lee determined that he would leave a squad of Major Gangl’s best troops to keep watch over the castle until he could return with reinforcements.

Night had just begun to fall on May 4, 1945 when the captain finally came back. As the castle gates cautiously creaked open, the French prisoners peered out anxiously. Their faces couldn’t have expressed something other than disbelief and disappointment as they took in what awaited them—a motley crew of soldiers, consisting of a single timeworn tank, 7 American GIs, and ten former German artillerymen, hardly the overwhelming force they had counted upon. To them, the word “cavalry” suggested a grand display of military might and brawn, but instead they were met with a ragtag band of troopers and an overweening captain with a makeshift plan to defend the castle walls from the approaching Waffen-SS troops. In fact, Lee’s plan was hardly a plan at all, but rather a desperate improvisation: with insufficient vehicles to move everybody back to the liberated Kufstein, he made the bold decision to dig in and wait for the likely arrival of American forces.

The Battle for Castle Itter

About one hour before midnight, the Waffen-SS troops stationed in the hills surrounding Schloss Itter opened fire on the 41 Allied defenders holed up inside: 20 Germans, 14 French, and 7 Americans. The shooting continued sporadically through the night until dawn, when the situation escalated dramatically. The SS troops began pounding the castle’s exterior walls with machine guns and 88mm antitank guns. One shell landed on the upper floor of the main building, destroying the empty room where General Gamelin had been staying; another slammed into Besotten Jenny, just as Corporal Szymcyk was preparing to fire at the SS troops in the village. “Stinky” managed to jump out of the vehicle and run for cover a mere second before the gas tanks exploded, engulfing Besotten Jenny in metal-melting, confidence-shattering flames. That’s when the main assault began.

SS troops swarmed from the east and headed towards the castle’s main gate while others scrambled up the hill on the west to reach the relative cover of the lower walls. The American and German defenders—not excluding the French notables!—fired from the castle’s upper walls and loopholes, taking a heavy toll with their rifles and machine guns. Despite the fierce resistance, the SS troops managed to breach the castle’s outer defenses and were on the verge of breaking into the interior when rrriiing rriiing—the telephone suddenly blared! It was Major Kramers, calling to inform Captain Lee of the imminent arrival of his unit. Out of ammunition and ideas, Lee accepted Borotra’s brave offer to leave the castle and guide the relief force through the village’s streets. If the force didn’t arrive in time, his only plan was to withdraw all defenders and the French VIPs into the castle’s massive keep to make the SS men fight for every inch of the place, for every Allied drop of blood.

At approximately 3 pm on May 5, just as the SS had settled in to launch a panzerfaust attack at the front gate of Itter Castle, a German soldier perched high up in the keep cried out, “Amerikanische panzer!” his voice trembling with joy and excitement. The sight of the approaching US troops and Austrian partisans demoralized the SS soldiers, who quickly surrendered. “The tank was still burning,” Hans Fuchs remembered in 2015. “I saw how around 100 SS men were taken prisoner… They had to give up everything and were taken away on lorries.” The fierce battle for Itter Castle was finally over. Throughout the siege, Captain Lee had displayed an extraordinary calm, and he continued to maintain his composed demeanor as he walked up to one of the rescuing tank commanders after the victory. Looking him squarely in the eye, he mustered up a hint of annoyance and quipped, “What kept you?”

The aftermath

Of all the strange things World War II brought, the Battle for Castle Itter may have been the strangest one. To sum up and stress, it featured beleaguered American and Wehrmacht soldiers fighting alongside each other against heavily armed SS troops to save the lives of 14 high-profile Frenchmen imprisoned at a medieval Austrian castle, high in the Alps. When written like that, it must sound like a made-up story, but it’s nevertheless a true one, worthy of a Hollywood movie adaptation (in the easily justifiable opinion of historian Andrew Roberts). Moreover, it is also a story about the reclaimed future of a war-scarred country, as Stephen Harding—the author of the defining book on the subject, The Last Battle—has dared to speculate. “If the SS had managed to get into the castle and kill the French VIPs,” he told the BBC in 2015, “the history of post-war France would have been radically different. These people formulated the policies that carried France into the 21st century. Had they died, who knows what would have happened?”

Fortunately, we know what did happen after they survived. Both Édouard Daladier and Paul Reynaud returned to politics, becoming members of the Chamber of Deputies soon after the war. Over the following decade, Reynaud held several important cabinet posts—including minister of finance and economic affairs—whereas Daladier acted as mayor of Avignon from 1953 to 1958. Michel Clemenceau served as a member of the National Constituent Assembly from 1946 to 1951. Leon Jouhaux, who resumed his role as president of the General Confederation of Labor, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in 1951, three years before passing away. His Itter mistress, Augusta Bruchlen, became his wife, as well as an important labor leader in her own right, and even a Grand Officier of the Légion d’honneur. Finally, both Jean Borotra and Maxime Weygand were cleared of charges for collaborating with the Vichy French government, no doubt in part due to their heroics at Itter.

The story of Captain John Lee, a Distinguished Service Cross recipient, is much more melancholic. He attempted to jumpstart his postwar life by running for the Democratic nomination for county sheriff, but lost the election by a substantial margin. He turned to sports and played several seasons of minor league football with the New Jersey Giants, before getting a job as a bartender, and going into the hospitality business—but was ultimately unsuccessful in everything. Divorced twice due to his heavy drinking, he died of acute alcohol poisoning at the relatively young age of 54. Whereas his name is largely forgotten today, that of his unlikely brother-in-arms Major Josef “Sepp” Gangl is certainly not. The only Allied casualty at Itter, he is nowadays regarded as a national hero in Austria; several streets in the country are named in his honor; and the plaque at the German Resistance Memorial Center in Berlin has, among 77,000 others, him in mind too. “You did not bear the shame,” it says. “You resisted. You bestowed the eternally vigilant signal to turn back by sacrificing your impassioned life for freedom, justice and honor.”