In 18th-century England, a quiet revolution in garden design led to the construction of ornate hermitages. These structures were often built to symbolize wealth and status, as they were seen as a fashionable and exotic addition to a well-manicured garden. But it wasn’t just the design of the hermitages that was a bit odd—in many cases, the hermitages also served as home to an actual, real-life hermit!

Wealthy landowners often hired these hermits to add an air of mystery and romance to their gardens and provide entertainment for their guests. Though the practice of building hermitages or hiring hermits has largely disappeared today, it remains a fascinating part of 18th-century English history.

So, let’s take a look at the hermits who lived in these hermitages, their roles in the garden, and some of the stories that have been passed down about them!

English landscape garden

During the 18th century, many of the formal gardens of the grand estates in England underwent a fairly drastic aesthetic change. Without going into too many details, suffice to say that they moved away from the rigidly formal, geometric style of the Baroque period and transitioned to a more naturalistic, untamed design. This new style was called the English Landscape garden.

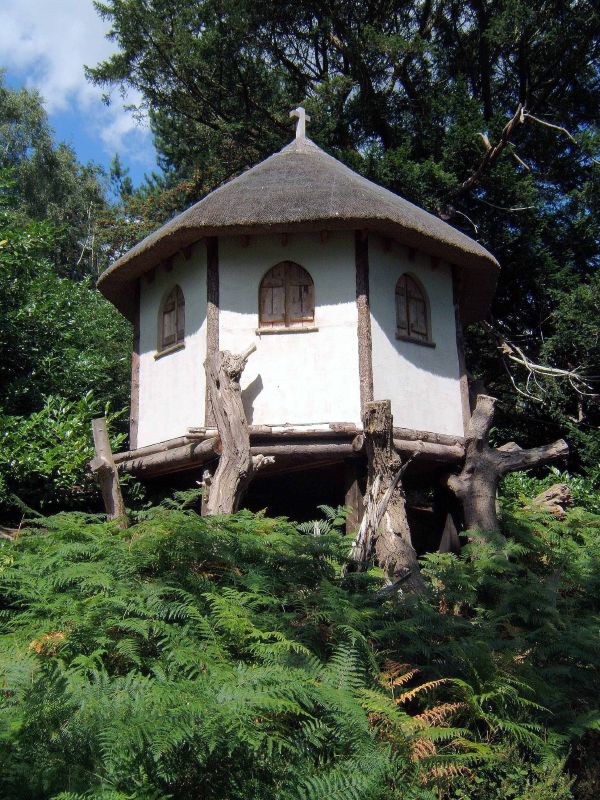

As part of this radical new style, many wealthy landowners began adding hermitages to their gardens—small, rustic structures meant to be used as retreats or places of contemplation. Often tucked away in groves of trees, and surrounded by wildflowers and other natural features, the hermitages were meant to evoke a sense of remoteness and quiet, while exuding an ancient and romantic atmosphere.

Inside, the hermitages were often sparsely furnished, with a few benches, a writing desk, and maybe even a fireplace—and, rather unbelievably, a live-in hermit! Acting as a living piece of garden art, the hermit would often be hired to live in the hermitage, wandering the grounds and occasionally conversing with visitors, providing a sense of authenticity to the landscape.

Origins and predecessors: a brief history of hermitages

According to Gordon Campbell—Professor of Renaissance Studies at the University of Leicester and author of the seminal work on the subject, The Hermit in the Garden: From Imperial Rome to Garden Gnome—the concept of the hermitage can be traced back to a small villa-like house the Roman Emperor Hadrian built for himself near Tivoli, at the beginning of second century AD. After the fall of Rome three centuries later, Hadrian’s villa was abandoned and left to the elements for a full millennium, until it was rediscovered by the artists of the Renaissance.

Pirro Ligorio—chief papal architect under Popes Paul IV and Pius IV—began to excavate the site in 1558 in what Campbell deems “the first modern archaeological dig.” A bit later, when he was tasked with building a solitary retreat for Pope Paul IV, Ligorio used Hadrian’s villa as his main inspiration for designing and decorating an elegant garden house. Known today as Casina Pio IV (as it was completed during the pontificate of Pope Pius IV), the house was quite influential—and not just architecturally but also conceptually, as it popularized the idea of the small garden retreat, located close to one’s official residence.

However, the earliest well-documented hermitage predates Casina Pio IV by several decades. It was built in the early years of the 16th century by Italian garden designer Pacello da Mercogliano at the Château de Gaillon, the first Renaissance château in France. The hermitage was located within a private retreat of the main garden called Le Lydieu, which also contained a small house and a chapel. Even though (by contemporary accounts) it was “as beautiful and alluring and charming as any that you will find elsewhere,” this lovely little hermitage produced no real descendants in all of France—though it might have influenced a few similarly-styled structures in Spain and Central Europe, raised a full century later.

What’s a hermitage without a hermit?

Much like the garden hermitage, the first garden hermits also appeared in southern Europe, particularly in Italy, and France. It is not unlikely that the trend started quite accidentally, with Francis of Paola, an Italian mendicant friar of the 15th century. Having spent many years of his life living in secluded caves on the coast of Italy, in 1483, Francis was summoned to the court of France, to attend the dying King Louis XI. He stayed there for the next 24 years, tutoring the heir, Charles VIII, and occasionally entertaining his guests while living ascetically in a small monastery built for him within the palace gardens.

Be that as it may, neither hermitages nor garden hermits became a thing until the 18th century and the English Landscape garden revolution, when—as Edith Sitwell sarcastically remarked in her 1933 self-published book English Eccentrics—”Nothing, it was felt, could give such delight to the eye, as the spectacle of an aged person with a long grey beard, and a goatish rough robe, doddering about amongst the discomforts and pleasures of Nature.”

Indeed, most of the surviving garden hermitages are located in England, with half a dozen known to have been built in Scotland, and nine or 10 in Ireland. As Gordon Campbell explains in The Hermit in the Garden, at the core of this trend lay an ideology bound by place and time—the profoundly Georgian notion of “contemplative solitude and pleasurable melancholy,” first made fashionable by John Milton in his influential poem Il Penseroso, and then picked up by a host of 18th-century poets and thinkers, who celebrated the beauty and spiritual benefits of nature and solitude.

Finding pleasure in melancholy may appear strange to contemporary readers, as we associate the very word with dark feelings, such as depression and despair. However, in the 18th century, melancholy was widely accepted—and even embraced. Sadness, in general, was viewed as something to be nurtured and was even seen as a sign of emotional depth and wisdom. Only smart people were considered deep enough to be sad for no obvious reason. By extension, hiring a garden hermit—a disheveled individual who prefers holy hardship to cursory comfort—was considered a metaphysical memento and a sign of spiritual refinement, a public demonstration of one’s appreciation for the unearthly benefits of seclusion, serenity, and subtle sorrow.

Help wanted: Garden hermits

Whereas building a hermitage was easy for a wealthy Georgian Era English landowner, recruiting an ornamental hermit to live in it wasn’t. Many people didn’t consider the hermit lifestyle desirable, and even fewer wanted to be a mere garden ornament. As a result, these ornamental hermits were often just that, as, in reality, they were agricultural workers dressed in costumes. Moreover, many of the individuals who did apply for the position of garden hermit were later found to be frauds, who were not truly interested in living a hermit’s solitary life but sought the position for financial gain.

Either way, in an effort to find the most suitable candidate for the position, advertisements for hermits were commonly placed in newspapers and magazines of the time. These advertisements were often quite specific in their requirements, seeking well-educated individuals who had a knowledge of classical literature, and could converse intelligently with visitors. One such ad, perhaps the most famous of its kind, stated the following conditions:

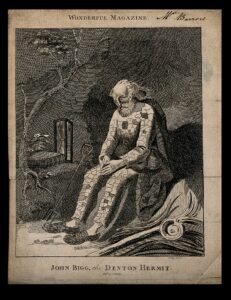

The hermit must continue on the hermitage seven years, where he shall be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a hassock for his pillow, an hourglass for timepiece, water for his beverage, and food from the house. He must wear a camlet robe, and never, under any circumstances, must he cut his hair, beard, or nails, stray beyond the limits of Mr. Hamilton’s grounds, or exchange one word with the servant.

If the hermit fulfilled their seven-year contract without violating any of the imposed restrictions, they were promised the reward of 500 guineas. However, any violation of the conditions or leaving the hermitage before the end of the contract would result in the forfeiture of the entire sum.

An ornamental hermit goes AWOL

Even though the original advertisement (stitched above from several sources) hasn’t been found to this day, there is enough evidence to suggest that it was a real one, and that it was placed sometime in the 1760s by member of parliament Charles Hamilton, whose then-estate Painshill, located near Cobham, Surrey, is still well known for its picturesque gardens and ornamental follies. A Christmas 1773 “Postscript” published by the London Evening Post reveals that a certain Mr. Remington applied for the position, and eventually became Hamilton’s garden hermit.

What happened next is anyone’s guess. We know for certain that Mr. Remington’s career didn’t last very long, and many contemporary sources claim that he gave up after only three weeks. The vast majority of them state that this wasn’t his choice to begin with, as he was actually dismissed from his post, after he was seen in the local tavern drinking beer. More recent research suggests that Mr. Remington’s sin could have been of a different nature, and that he was actually caught having improper relations with a dairymaid. Either way, we know for sure that he didn’t earn the £500. In fact, he earned not a single penny.

Remuneration for a resident hermit

At first glance, the sum of £500 promised to Mr. Remington as a reward for fulfilling his seven-year contract as an ornamental hermit may seem like a large amount of money, and many sources out there claim it was. But allow us to consider it in the proper context.

When adjusted for inflation, £500 in the 1770s equals approximately £120,000 today. While this may still seem like a substantial sum, let’s not forget that this amount would have to cover Mr. Remington’s living expenses for seven years. When broken down annually, Mr. Remington’s salary would have been around £17,000 per year— very far from an average salary of a modern professional, and quite lower than the median salary in many developed countries today.

This is one of the reasons why 18th-century noblemen had trouble finding authentic hermits willing to fill the role of an ornamental hermit, and had to rely on individuals who were not truly interested in the hermit lifestyle, but saw the opportunity for financial gain. They simultaneously paid a lot—and not enough.

In place of conclusion: an odd phenomenon with an odder afterlife

There was another reason why the hermit ads didn’t work as well as a modern reader might expect. Put in modern parlance; they were targeting the wrong audience—after all, an authentic hermit would have likely rejected the idea of a monetary reward altogether. Real hermits typically reject material possessions and worldly pleasures, instead embracing poverty and simplicity as a spiritual practice. Therefore, a financial reward would not be considered an attractive proposition for an individual who is committed to this lifestyle.

The trend of building ornamental hermitages in 18th-century England was a product of its time and culture, reflecting the values and tastes of the wealthy and powerful class of the era. The ornamental hermit was rarely an authentic spiritual practitioner, but rather a feature of the garden, meant to add a touch of romanticism and spirituality to the landscapes of the wealthy. The very idea of the garden hermit serves as a reminder of how different social customs and values were in the past, and how they differ from those of the present day.

That said, the memory of the garden hermit—and the ideology behind it—lives on, manifesting itself in several ways, perhaps most conspicuously in the form of the modern garden gnome. Often seen as a playful, whimsical addition to the landscape, garden gnomes are also a subtle reminder of their living, breathing ancestors: the resident hermits. So, the next time that you are out for a walk and notice a cute little garden gnome in your neighbor’s front garden, do spare a thought for his melancholy human precursor who once inhabited the gardens of the great estates of Georgian England—well, for a week or two.