In the labyrinth of British history, one figure stands out as a troubling enigma: Sir Oswald Mosley. He is perhaps best known as the founder and leader of the British Union of Fascists (BUF), a political movement that sought to emulate the fascist regimes of Benito Mussolini’s Italy and Adolf Hitler‘s Germany on British soil. The story of Oswald Mosley and British Facism is a stark reminder of a period in British history when fascist ideologies briefly found a foothold. As we delve deeper into the life of this controversial figure, we unearth a chilling chapter in the annals of British politics, one that resonates with eerie familiarity even today.

Early life of Oswald Mosley

Born into the English aristocracy in 1896, Oswald Mosley was the eldest of three sons of Sir Oswald Mosley, 5th Baronet, and Katharine Maud Edwards-Heathcote. The Mosley family had a long lineage in British politics, tracing their roots back to the time of William the Conqueror. A privileged childhood, nurtured in the sprawling estates of Staffordshire, set the stage for Mosley’s entry into the political arena.

Mosley’s education began at home, under his mother’s and governess’s strict tutelage. Later, he attended Winchester College, a prestigious boarding school. His academic performance was middling, but he distinguished himself as a skilled fencer. At 19, Mosley abandoned his education to serve in World War I. The war years would harden him, providing a brutal introduction to the realities of the world beyond his aristocratic upbringing.

Following the war, the young Mosley, barely 21, embarked on his political journey, winning the Harrow seat as a Conservative Party MP in 1918. However, his political ideology remained fluid during these early years. His biographer, Stephen Dorril, said, “In the 20s, he was a fashionable figure. He knew Winston Churchill; he knew all the politicians. A massive womanizer—he was very tall for the time, although he had a limp. He lived life to the full.”

Over the subsequent decade, his political loyalties would shift twice. Initially, he allied with the Labour Party in 1924, but growing disillusionment with conventional politics led him to establish the New Party in 1931. This political journey, characterized by ideological transformations and personal aspiration, ultimately steered Mosley towards a course significantly divergent from Britain’s traditional political terrain.

Forbidden love

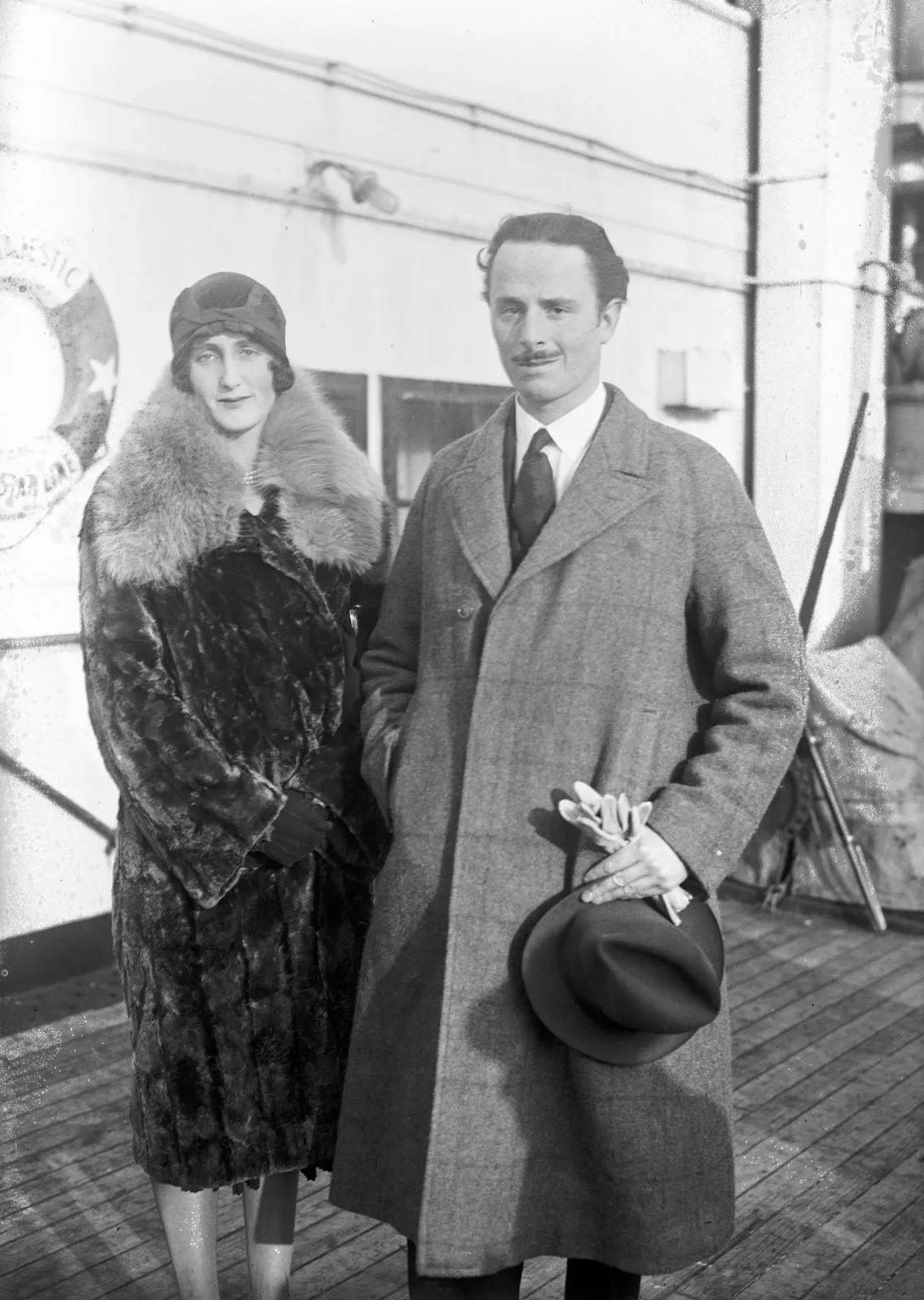

In 1922, Mosley took Lady Cynthia Curzon as his wife. Throughout his marriage to Lady Cynthia Mosley, he initiated a prolonged affair with his wife’s younger sibling, Lady Alexandra Metcalfe. Concurrently, he engaged in a separate liaison with their stepmother, Grace Curzon, the Marchioness Curzon of Kedleston. The American-born Grace was the second spouse and widow of Lord Curzon of Kedleston. Tragedy struck in 1933 when Cynthia died at age 34 from peritonitis, a complication of acute appendicitis, in London.

Sir Oswald Mosley’s second marriage took place in 1936, uniting him with Diana Mitford in a secret ceremony in Germany. The event was hosted at the home of Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, with Adolf Hitler as a guest of honor. This marriage, deeply intertwined with Mosley’s political affiliations, cemented the couple’s notoriety within both British society and the escalating fascist movement in Europe.

Political ascendancy

Mosley’s political career before the formation of the British Union of Fascists was marked by dynamism and a certain level of unpredictability. After serving as a Conservative MP for Harrow from 1918 to 1924, Mosley defected to the Labour Party, driven by a sense of dissatisfaction with the conservatives’ approach to social issues, especially unemployment.

As a Labour MP for Smethwick, Mosley quickly rose through the ranks. His charisma, coupled with his aristocratic allure, made him a figure to watch within the party. In 1929, in the aftermath of the Wall Street Crash, Mosley was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, a position that placed him at the heart of the government’s efforts to combat unemployment.

However, Mosley’s innovative proposals, which included large-scale public works funded by deficit spending, were rejected by the Labour Government. This rejection marked a significant turning point in Mosley’s political trajectory. Disillusioned, he resigned from his ministerial position in 1930 and from the Labour Party soon after. According to Dorril, “He was incredibly egotistical. He believed he was the right man. He believed that he had the solution.”

In 1931, Mosley founded the New Party. Although initially, it presented itself as a radical, yet mainstream political force, the New Party’s undercurrents of authoritarianism and its paramilitary stewards known as “biff boys” hinted at the more extremist path Mosley was about to embark upon. A tour of Mussolini’s Italy in 1932 would solidify this path, ultimately leading to the formation of the British Union of Fascists.

Formation of the British Union of Fascists

The birth of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1932 marked a significant shift in the political landscape of Britain. The formation of the BUF was a culmination of a series of events and influences that shaped Mosley’s political philosophy and ambitions.

As the New Party failed to secure any seats in the 1931 General Election, Mosley sought new political inspiration, which he found during a trip to Italy. Deeply impressed by the strides made under Benito Mussolini’s fascist regime, Mosley began envisioning a similar model for Britain.

His trip to Italy was a transformative experience that significantly influenced the formation of the BUF. Fascinated by Mussolini’s strong leadership and the apparent efficiency of the fascist state, Mosley started envisioning a new political order for Britain that would combine his economic program with the authoritarian structure of Italian Fascism.

On returning to Britain, Mosley dissolved the New Party and announced the formation of the British Union of Fascists. The BUF was a clear departure from conventional British politics, adopting the Blackshirt uniform symbolic of Italian Fascism, and advocating for a new political order that promised national renewal through authoritarian leadership and corporatist economics.

Mosley’s BUF, blending his economic program with explicit anti-Semitism, was a stark contrast to the multi-party democratic politics that characterized Britain. The BUF symbolized Mosley’s personal transformation, from a mainstream politician to a proponent of a political doctrine that was both radical and, for many Britons, deeply unsettling. The formation of the BUF was a clear testament to the profound influence of Italian Fascism on Mosley’s political thought and ambitions.

Ideology of the British Union of Fascists

The ideology of the British Union of Fascists was a blend of Mosley’s economic theories, explicit anti-Semitism, and the authoritarian principles of Italian Fascism. The crux of their belief lay in creating a self-sufficient national community, united under a strong and authoritative leadership.

Mosley’s economic program formed a vital part of the BUF’s ideology. He proposed radical economic reforms aimed at reducing unemployment and boosting national self-sufficiency. The BUF advocated for a planned economy, replacing the existing laissez-faire system with corporatism, where each industry would be governed by a corporation representing employers, employees, and the state.

The BUF’s ideology was also marked by a virulent form of anti-Semitism. Mirroring the growing anti-Semitic sentiment in European fascism, particularly in Nazi Germany, the BUF blamed Jews for many of the nation’s economic and social problems. This anti-Semitic stance was a significant departure from Mosley’s earlier political career but became a defining feature of the BUF’s ideology.

The influence of European fascism, particularly Italian Fascism and German National Socialism, was evident in the BUF’s ideology. Mosley admired the authoritarian leadership of Mussolini and Hitler and sought to implement similar principles in Britain. He believed in strong central leadership, where power was concentrated in the hands of a single leader who would act decisively and efficiently for the nation’s benefit.

Despite these shared principles, the BUF also distinguished itself from other European fascist movements. Unlike the militaristic expansionism of Nazi Germany, the BUF claimed to be a peace movement, arguing that their goal was national renewal and prosperity, not war.

The BUF’s ideology was a complex mix of economic radicalism, anti-Semitism, and authoritarianism, all underpinned by a commitment to national unity and renewal. Influenced by European fascism, but tailored to the British context, it was a political ideology that both fascinated and horrified the British public.

Leadership style of Oswald Mosley

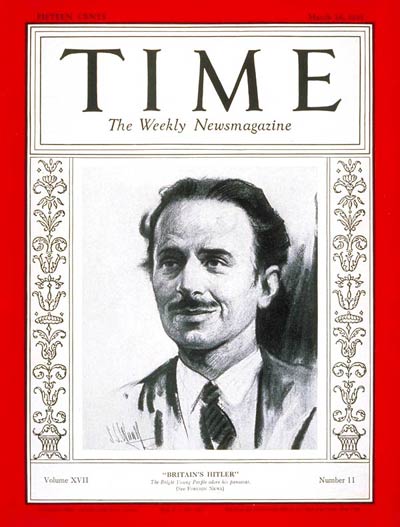

One of the most defining aspects of Oswald Mosley’s political career was his charismatic persona and leadership style. His aristocratic bearing and his talent for public speaking made him a captivating figure to his followers and his many detractors.

Mosley’s leadership approach was marked by a level of personal magnetism that was unusual in the dry and often staid world of British politics. As Stephen Dorril, Mosley’s biographer, noted, “He was an exceptional speaker,” and his appeal was rooted in his compelling oratory and commanding presence. This is not to say that Mosley’s charisma was universally appealing —to many, his authoritative style was unnerving and his politics deeply disturbing. Yet, there is no denying that his dynamic personality significantly drew people to the BUF.

Mosley’s leadership approach was, in many ways, similar to the authoritarian style of the European fascist leaders he admired. He was the undisputed leader of the BUF, his word was law within the party, and he was the primary architect of its policies and strategies. This concentration of power allowed Mosley to shape the BUF in his image, and to steer it towards his vision of a fascist Britain.

The impact of Oswald Mosley’s leadership style on the BUF’s growth and operations was substantial. His charisma helped to attract a considerable following, and his authoritative leadership kept the party focused on its goals. Mosley’s dynamic public performances, often in uniform and delivering fiery speeches, became the hallmark of the BUF’s propaganda efforts.

However, Oswald Mosley’s leadership style also had its downsides. His authoritarian approach stifled dissent within the BUF, and his unwavering belief in his own ideas and strategies led to strategic missteps. Furthermore, his charismatic persona could not fully mask the BUF’s ideology’s extremist nature, eventually leading to public backlash and government opposition.

Oswald Mosley’s charismatic and authoritarian leadership style was a key factor in the rise of the BUF. It shaped the party’s identity, influenced its operations, and significantly influenced its initial growth. However, it also contributed to the BUF’s eventual decline, highlighting the double-edged nature of charismatic leadership.

Membership and recruitment

Like any political movement, the British Union of Fascists was not solely defined by its leader but also by the people who were drawn to its banner. The profile of BUF members was as diverse as the various political, economic, and social currents that converged in Britain during the interwar period.

The BUF attracted people from all walks of life, including disgruntled war veterans, unemployed workers frustrated by the economic downturn, and even members of the aristocracy drawn by Mosley’s personal charisma and promise of a new political order. The party claimed at its height to have 50,000 members, a number that, while not insignificant, represented a mere fraction of the British population.

Recruitment strategies of the BUF focused on large public meetings, often held in working-class neighborhoods hit hard by the Great Depression. Mosley’s powerful oratory, coupled with the spectacle of uniformed Blackshirts marching in formation, created a potent propaganda tool that helped draw in new members. The BUF also made extensive use of print media, with its newspaper, “The Blackshirt,” playing a key role in disseminating the party’s message and attracting followers.

Another notable aspect of BUF recruitment was the so-called “biff boys,” a group of toughs who provided security at BUF events and were notorious for their violent tactics. The presence of these strongmen both intimidated opposition and provided a sense of power and purpose to those who felt marginalized by society, further attracting individuals to the party.

However, the recruitment efforts of the BUF were not without their challenges. The party’s overtly fascist ideology and anti-Semitic rhetoric were a significant barrier to wider acceptance. As historian Stephen Dorril notes, “the British don’t like people parading around in uniform,” highlighting the cultural disconnect that hampered the BUF’s broader appeal.

In conclusion, the membership and recruitment strategies of the BUF were a reflection of the social and political tensions of the time, as well as the charismatic appeal of Oswald Mosley. However, they also underscored the limitations of the BUF’s extremist ideology in a British society that was deeply suspicious of authoritarianism and political extremism.

Media and propaganda

The British Union of Fascists made effective use of media and propaganda to promote its ideology and shape public opinion. This propaganda campaign was orchestrated using a variety of media platforms, including print, radio, and public speeches, and played a crucial role in the BUF’s operations.

The BUF’s newspaper, “The Blackshirt,” was instrumental in propagating the party’s message. The paper published articles espousing the virtues of fascism, vilifying its enemies, and glorifying Oswald Mosley. “The Blackshirt” served not only as a recruitment tool but also a means to galvanize existing members, reaffirming their ideological commitment and fostering a sense of collective identity.

In addition to “The Blackshirt,” the BUF also capitalized on Mosley’s oratorical prowess, which was a key element of the party’s propaganda strategy. Mosley’s fiery speeches, delivered at public meetings and rallies, were designed to captivate audiences, stoke emotions, and convince listeners of the righteousness of the BUF’s cause. His charismatic persona further enhanced his public appeal, making him a potent symbol of the BUF’s ideology.

The BUF also made use of visual propaganda, including the black uniforms worn by its members. These uniforms, reminiscent of those worn by Mussolini’s Blackshirts in Italy, were designed to project an image of discipline, unity, and power. They also served to differentiate BUF members from the crowd, creating a sense of exclusivity and purpose.

Despite these efforts, the BUF’s propaganda campaign was met with considerable resistance. Many Britons, particularly those with liberal or leftist leanings, viewed the BUF and its message with suspicion and hostility. The party’s anti-Semitic rhetoric, in particular, was a source of widespread condemnation.

As historian Stephen Dorril points out, the BUF’s propaganda machine was ultimately unable to overcome the deep-seated cultural and political norms that shaped British society. Despite its best efforts to manipulate public opinion, the BUF remained a fringe movement, unable to achieve widespread acceptance or political success.

In the end, the BUF’s use of media and propaganda was a double-edged sword: while it helped to attract followers and spread the party’s message, it also alienated many Britons and contributed to the BUF’s marginalization and eventual demise.

Uniforms and iconography

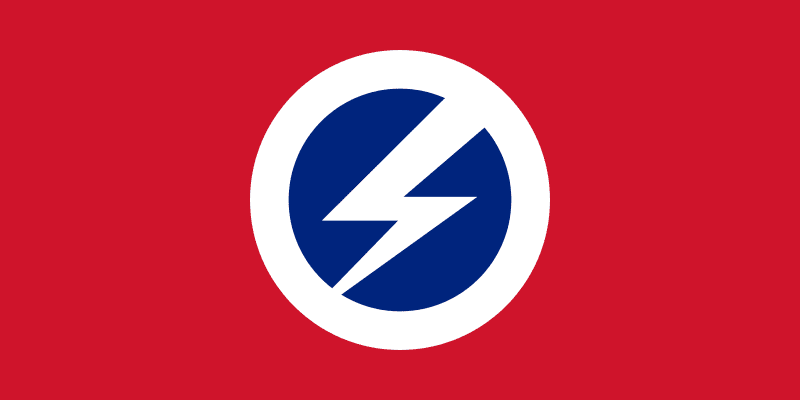

Uniforms and iconography were a significant part of the British Union of Fascists’ identity. They served as a means of unifying the members, creating an intimidating spectacle, and offering an immediate visual representation of the party’s ideology.

The BUF’s most recognizable symbol was its uniform. BUF members, also known as Blackshirts for their distinctive apparel, donned black paramilitary-style uniforms similar to those of Mussolini’s squadristi in Italy. The use of a uniform was a deliberate choice by Mosley, intended to promote discipline, cohesion, and a strong visual identity. However, it was this uniform that led to the Public Order Act 1936, which prohibited the wearing of political uniforms in public, a direct response to the violent clashes incited by the BUF.

The lightning bolt enclosed in a circle, another powerful emblem adopted by the BUF, held a particular significance. The lightning bolt symbolized action and power, while the circle represented unity and inclusivity, reinforcing the BUF’s message of national unity under a strong, central authority.

The BUF also used the fasces, a bundle of rods with an axe, a common symbol of authority in ancient Rome. It represented strength through unity, a key principle of fascist ideology. The fasces was incorporated into the BUF’s insignia, further aligning the party with the broader fascist movement in Europe.

However, the BUF’s uniforms and symbols were not merely aesthetic choices. They were part of a broader strategy aimed at creating a sense of collective identity and purpose among its members. By donning the black uniform and aligning themselves with the BUF’s symbols, members were publicly demonstrating their allegiance to the party and its ideology. This commitment, in turn, bolstered the party’s cohesion and operational effectiveness.

Yet, these uniforms and symbols also contributed to the BUF’s notoriety and eventual downfall. To many Britons, they were a potent symbol of the party’s extremism and willingness to resort to violence. The black uniform, in particular, became a lightning rod for public criticism and government scrutiny, culminating in the passage of the Public Order Act 1936.

In the final analysis, the BUF’s uniforms and iconography were a defining feature of the party, shaping its public image and influencing its political trajectory. They were a testament to the power of visual symbolism in politics – a power that can be wielded for good or ill, depending on the intentions and actions of those who use it.

Public perception and controversy

Public perception of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a complex brew of intrigue, repulsion, and fear. While Mosley’s charisma and the party’s passionate rhetoric drew some towards the BUF, the majority of the British public regarded the BUF with apprehension and disdain.

From its inception, the BUF was seen by many as an extremist group. Their adoption of fascist ideologies, their paramilitary-style uniforms, and their aggressive tactics all contributed to an image that was far removed from the traditional British political scene. Even at the height of their popularity, the BUF was viewed with suspicion and unease by the mainstream.

Public opinion was further swayed against the BUF due to their violent confrontations with anti-fascist groups and their virulent anti-Semitism. The infamous Battle of Cable Street in 1936, where local residents and anti-fascist protesters prevented the BUF from marching through a predominantly Jewish area in East London, is a prominent example of the public resistance faced by the BUF. As noted by Time magazine, Mosley’s plans to march through a Jewish neighborhood was met with staunch opposition from locals, demonstrating the extent to which the BUF had alienated themselves from the general populace.

Media coverage of these events, often highlighting the BUF’s aggression and militancy, further tarnished their public image. The BUF was largely portrayed as a threat to public order and the democratic way of life, a perception that was cemented with the passing of the Public Order Act in 1936. This legislation, introduced in direct response to the BUF’s activities, effectively curtailed the party’s ability to hold public rallies and wear their iconic black uniforms.

Even within the realm of the far-right, the BUF was not without controversy. Many traditional conservatives were uneasy with the BUF’s overtly fascist leanings and their alignment with foreign dictators. Mosley’s connections with Mussolini and Hitler, including Hitler being the guest of honor at his wedding, further isolated the BUF from mainstream conservative politics.

To put it simply, the BUF was widely regarded as an unwelcome import of foreign extremism in a nation that prized moderation and civility. Their violent methods, alien ideology, and controversial leadership all contributed to a largely negative public perception, leading to their ultimate downfall.

Government reaction and legislation

Despite the controversy and public consternation, the British government initially adopted a stance of watchful neutrality towards the British Union of Fascists (BUF). The traditional British policy of laissez-faire and upholding the freedom of speech allowed the BUF to propagate its ideology relatively unimpeded in the early years. However, as the BUF’s influence grew and their actions increasingly disrupted public order, the government began to take a more interventionist stance.

The turning point came with the Public Order Act of 1936. This legislation was a direct response to the escalating violence and disruption associated with the BUF’s activities, particularly their public marches and the wearing of paramilitary-style uniforms. The Act imposed a ban on political uniforms, a measure specifically aimed at the BUF’s blackshirts, and required police consent for political marches. It was a significant blow to the BUF, curtailing their public visibility and ability to demonstrate en masse. According to Tribune, the Act was seen as a clear signal of the government’s disapproval and an attempt to rein in the BUF’s activities.

But the most decisive action came with the outbreak of World War II. In 1940, with Britain at war against the very fascist powers that the BUF had openly admired, the government enacted Defence Regulation 18B. This legislation allowed for the internment of individuals believed to be a threat to national security. Mosley, along with hundreds of other BUF members, was detained under this regulation. His internment marked the end of the BUF as a significant political force and reflected the government’s firm stance against domestic fascism during the wartime period.

While the British government’s initial response to the BUF may have been one of cautious neutrality, the rise of fascism in Europe and the BUF’s growing notoriety led to a significant shift. The introduction of legislation such as the Public Order Act and Defence Regulation 18B demonstrated the government’s readiness to take action against the perceived threat posed by the BUF. It was a clear repudiation of the BUF’s ideology and tactics, and marked the end of the BUF’s brief but tumultuous existence on Britain’s political stage.

The BUF during World War II

As Britain prepared for war against the Axis powers, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) found itself in an increasingly precarious position. While Mosley had always espoused an anti-war stance, arguing for a negotiated peace with Germany, the BUF’s sympathetic leanings towards fascist Italy and Nazi Germany did not bode well for its future.

When war was declared in 1939, the BUF’s stance was one of ‘Mind Britain’s Business’. This isolationist policy was seen by many as a thinly veiled attempt to protect the fascist regimes in Europe. Mosley’s speeches during this period, full of vitriol against the ‘war-mongers’ of the government, did little to dispel these suspicions.

The outbreak of war had serious repercussions for the BUF. Public opinion swiftly turned against the party as Britain rallied against the Axis powers. The BUF’s membership dwindled, and the party found itself increasingly isolated. The government, viewing the BUF as a potential fifth column, decided to take action. In May 1940, Defence Regulation 18B was enacted, leading to the internment of Oswald Mosley and other prominent BUF figures.

Mosley’s internment was largely unopposed, reflecting the public mood of the time. Mosley was released in 1943 due to health issues but remained under house arrest until the end of the war. The BUF was proscribed later in 1940, effectively ending its operations.

World War II marked a turning point for the BUF. The party’s sympathy for fascist regimes and anti-war stance put it at odds with the government and the public. The war led to its leaders’ internment and the BUF’s eventual dissolution. The wartime period encapsulated the BUF’s rapid rise and fall, a testament to the volatile nature of political extremism.

Dissolution of the BUF and aftermath

With its leaders’ internment and the party’s proscription, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) met its practical end during the Second World War. The party that had once boasted 50,000 members was no more, a casualty of the very conflict that its fascist brethren had ignited.

However, the story did not end there for Oswald Mosley. Released from internment in 1943 due to his ill health, he sought to reenter the political scene after the war. In 1948, Mosley formed a new party, the Union Movement (UM), seeking to capitalize on post-war discontent. The UM advocated for a united Europe, a radical idea at the time, and one that Mosley believed was the only way to prevent future wars.

Despite his attempts to reinvent himself and his ideology, Mosley’s new venture failed to gain traction. His attempt to stand for election in Kensington North in 1959 on an anti-immigration platform was unsuccessful. He tried again in the 1966 general election but failed to make a significant impact.

Frustrated and disillusioned, Mosley left Britain for France in 1951, where he lived in self-imposed exile until his death in 1980. The BUF, the party he had built and led, was a distant memory. Yet, its shadow lingered on, a chilling reminder of the time when fascism found a foothold in Britain.

While the BUF was dissolved, its legacy lived on, influencing a number of far-right movements in the UK. Despite the failure of the Union Movement and subsequent political endeavors, Mosley’s brand of fascism left an indelible mark on the British political landscape. It served as a stark reminder of the dangers of extremism, and the enduring allure of charismatic leadership.

Legacy of Oswald Mosley and the BUF

The end of the British Union of Fascists and Oswald Mosley’s self-exile to France did not spell the end of their impact on the British political landscape. Instead, they left a legacy that continues to influence the nation’s encounter with far-right ideologies.

Despite his political failures, Mosley’s charismatic leadership style and his ability to galvanize a significant following, albeit briefly, left an indelible mark on British politics. His charisma, combined with his political ideology, set a precedent for future far-right movements in Britain. Mosley demonstrated that even in a country known for its steady democracy, extremism could find fertile ground.

The BUF’s influence can be seen in various far-right movements that emerged in post-war Britain, including the National Front and the British National Party. These groups borrowed elements from Mosley’s ideology, such as nationalism, anti-immigration sentiment, and the exploitation of economic discontent.

In recent times, the specter of Mosley and the BUF has been invoked in discussions about the rise of right-wing populism in the UK and elsewhere. Some observers see parallels between Mosley’s use of economic discontent and populist rhetoric and the tactics employed by contemporary far-right groups and politicians. Mosley’s ideas still resonate with some, for better or worse.

However, it is also important to note the considerable backlash and resistance Mosley and the BUF faced. The Battle of Cable Street, the Public Order Act of 1936, and the wider opposition to fascism during World War II, all serve as powerful reminders of Britain’s rejection of Mosley’s extremist ideology. The legacy of this resistance continues to inspire anti-fascist and anti-racist movements in the UK.

In popular culture, Mosley’s persona has been resurrected in television series like “Peaky Blinders”, reminding a new generation of Britain’s brush with homegrown fascism. This depiction of Mosley is a reminder of the dangers of charismatic leadership when combined with extremist ideologies, a lesson that retains its relevance in contemporary political discourse.

The legacy of Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists is thus a complex one. It stands as a testament to the enduring allure of extremist ideologies, the potential dangers of charismatic leadership, and the ability of societies to resist such threats. It also serves as a cautionary tale for the present, reminding us of the need for vigilance in the face of extremism.

Lasting implications

The rise and fall of Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists is a significant chapter in Britain’s political history. It serves as a reminder of the country’s encounter with extremist ideologies, the dangers they pose, and the resilience of democratic values in resisting such threats. Mosley, despite his initial promise as a young politician, chose a path that led him to become a divisive figure, promoting an ideology that was ultimately rejected by the British people.

The story of the BUF underscores the dynamics of extremism and its appeal during times of economic and social uncertainty. Mosley’s charisma, his manipulation of economic discontent, and his nationalist rhetoric managed to draw a significant following. However, his vision of a fascist Britain was met with strong resistance, leading to the decline of his own political party and his eventual political marginalization.

Today, the legacy of Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists continues to resonate. As we grapple with the rise of right-wing populism and extremism in various parts of the world, the lessons from Britain’s encounter with fascism are more relevant than ever. The resistance against Mosley’s extremist ideology serves as a testament to the power of democratic values and the importance of remaining vigilant against threats to these principles.

As we delve into the depths of this turbulent chapter in British history, we are reminded of the words of historian Robert Gerwarth, “Fascism, as history shows us, is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon that requires careful and nuanced analysis.” Understanding the rise and fall of Oswald Mosley and the BUF provides us with a valuable perspective in our ongoing efforts to understand and confront extremist ideologies. It is a reminder of the importance of historical memory in shaping our responses to the challenges of the present.