In an era when noble women were expected to either marry and serve their lords, or take holy vows and serve God, Nicola de la Haye stands out as a strong, independent woman who served her country courageously at a perilous time. While she is not the only medieval woman to take on a military role, she had a decisive impact on the outcome of the First Barons War.

In her role as Sheriff of Lincolnshire and Castellan of Lincoln Castle, she defended her lands against French and rebel forces, earning herself the gratitude of King John and King Henry III, and securing herself an honored place in English history.

The early life of Nicola de la Haye

We aren’t sure exactly when Nicola de la Haye was born, because daughters weren’t considered important enough to record that information. The best guess is sometime between 1150 and 1156. Her parents were Richard de la Haye, a minor Lincolnshire lord, and his wife Matilda de Venon.

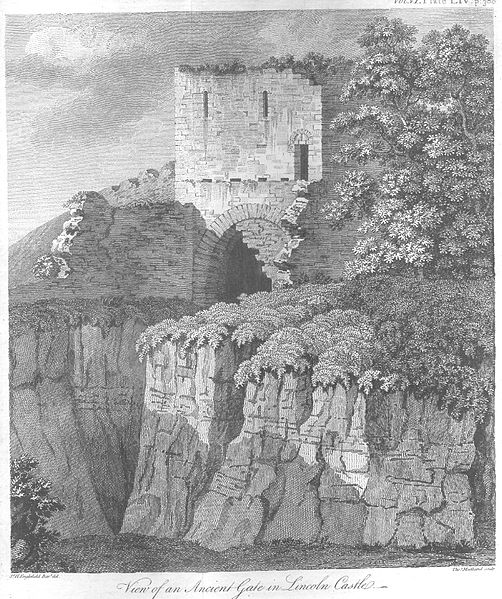

Sons were what mattered in medieval England, as the eldest male child would carry on the family title and inherit his father’s lands. However, the years went by, and no son was born to her parents, so upon her father’s death in 1169, Nicola, as the eldest daughter, inherited his estates, succeeding him as Hereditary Constable (or Castellan) of Lincoln Castle, one of the most important fortresses in England. She was still in her teens.

Of course, a wealthy heiress would not be able to stay single for long, and she soon married William Fitz Erneis, who died in 1178, leaving her a widow with one child, a daughter named Matilda. By 1185 she has married again. Her second husband was Gerard de Camville, with whom she had two sons, Richard and Thomas.

While her husbands assumed her titles and ownership of her land, as was customary, Gerard obviously had a great deal of confidence in her abilities, trusting her to manage things at Lincoln Castle in his absence.

Besieged in 1191

Gerard’s trust in his wife was certainly borne out in 1191.

While King Richard I was off fighting in the Third Crusade in the Holy Land, William Longchamp, his chancellor, was running England and making himself very unpopular in the process. Richard’s brother John, always ambitious, led the opposition to Longchamp’s rule, and Gerard rode off to Nottingham to fight by the prince’s side.

Gerard knew that Lincoln Castle was a target for Longchamp, as the chancellor had already demanded its surrender, but instead of appointing a man to lead the castle’s defense, he left his wife in charge.

Longchamp advanced on Lincoln and laid siege to the castle for 40 days before withdrawing in defeat, but things did not go well for Nicola and Gerard in the short term. When Richard returned to England in 1194, he punished them for siding with Prince John by taking away Gerard’s positions as Sheriff of Lincolnshire and Castellan of Lincoln Castle.

However, when John took the throne following his brother’s death in 1199, Gerard regained his titles and possession of the castle in recognition of his past support.

The widow Castellan

Gerard died in 1214 or 1215, and Nicola de la Haye, by then in her sixties, declared herself a femme sole who would control her own lands.

She was confirmed as sheriff and Castellan by King John in 1216. While those positions would usually have passed on to her son, John chose otherwise. And this was no mere courtesy appointment; a civil war was brewing in England, and John needed a strong leader in the key fortress of Lincoln Castle.

The Magna Carta

King John was not a good man; it is generally agreed. He was a despotic and erratic king who made enemies wherever he went. In 1215 his barons were so frustrated with his rule that they forced him to sign the Magna Carta, which bound the king to certain basic principles of government.

However, John did not intend to abide by those rules. He got the Pope to declare the Magna Carta invalid, excommunicate the barons, and lay an interdict on London so that no burials could be performed.

The first Barons’ War

In response to King John’s refusal to accept the Magna Carta, the barons invited Prince Louis of France to invade the kingdom, offering him the English crown. Starting in September 1215, John retaliated by seizing the lands of the rebel leaders and leading his army up the east coast of England, where the barons’ power was concentrated, burning towns as he proceeded north.

Prince Louis landed in May of 1216 with his French troops, and the invading forces soon captured key cities such as Winchester.

During the summer of 1216, Lincoln Castle was once again under siege, but Nicola arranged a truce with the leader of the occupying rebel army, Gilbert de Gant, by paying him off.

In October, John died, leaving his nine-year-old son Henry III to succeed him as the new king. Prince Louis continued to press his claim to the throne, however, and the war entered a new phase.

The second Battle of Lincoln

By the early months of 1217, Prince Louis and the rebel barons controlled much of England. Gilbert de Gant had returned and, this time, occupied the city of Lincoln, while only Lincoln Castle remained under the control of the royalist forces under Nicola’s command. This was a seven-month siege of the castle by a large force of combined French and rebel English forces.

The battle grew more intense in April and May as the French and rebel barons surrounded the castle walls, but relief was coming. On May 20th, William Marshall, regent for King Henry III and an experienced soldier, arrived and, within six hours, had routed the French and rebel army, ending the siege of Lincoln Castle. Following the victory, the royalist forces looted the city of Lincoln, which, unlike Lincoln Castle, had sided with Louis and the rebels. This sacking became known as the “Lincoln Fair.”

Not surprisingly, the two sides had a rather different opinion of Nicola after she successfully resisted the siege for seven months. Royalist writers called her “a worthy lady,” while the rebels and French saw her as “a very cunning, bad-hearted and vigorous old woman.”

The woman who saved England

Nicola de la Haye’s determination to defend Lincoln Castle was a major turning point in the civil war. Because she could hold off the besiegers until William Marshall arrived in Lincoln, the rebel forces and their French allies were either killed, captured, or forced to retreat. Half of Louis’s army was gone.

Finally, after being soundly defeated at the Battle of Sandwich in August, Prince Louis agreed to the Treaty of Kingston on September 12, 1217, ending the war with a complete victory for the royalist forces. The Baron’s War ended, and Henry III was secured upon the English throne.

The Lady of Lincoln Castle

Despite calling her “our beloved and faithful Nichola de la Haye,” King Henry III did not reward Nicola de la Haye. In fact, it was quite the reverse. A mere four days after the French and rebel forces were defeated at Lincoln, she was stripped of her position as sheriff.

Her son Richard, who might have been expected to inherit the title, had died in March 1217, so there was no direct heir. Instead, the king’s uncle, William Longspée, the Earl of Salisbury, was made Sheriff of Lincolnshire, and he also seized Lincoln Castle.

Now well into her sixties, Nicola could have just given up and settled into retirement, but she was made of sterner stuff. She headed off to London to plead her case before the young king’s regents.

As a result, she regained possession of Lincoln Castle and the city of Lincoln, while Salisbury continued as sheriff. The earl wasn’t happy about it, even after his grandson married Richard’s daughter Idonea, thus securing the inheritance for his family. The feud over the property continued until Salisbury’s death in 1226.

A vigorous old age

Throughout this period, Nicola administered her estates effectively. She issued 25 charters in her own name and donated to religious houses and Lincoln Cathedral. She also obtained a royal charter for a weekly market on one of her manors, which would have meant not just more profits for her estates but also for the inhabitants.

Following Salisbury’s death in 1226, she relinquished her position as Castellan of Lincoln Castle. It seems likely that she held out until Salisbury died so that her lands and positions would pass to her granddaughter Idonea and her husband William Longspée II rather than to her bitter rival.

Nicola de la Haye then retired to her manor at Swaton, where she died on November 20, 1230, well into her seventies. She was interred in the burial ground of St Michael’s Church at Swaton.